Young, Gifted and Black considers themes of race, class and politics, as well as the importance of human dignity.It is curated by The New Black Vanguard’s author Antwaun Sargent and artist Matt Wycoff, who together haveselected 50 works from the Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection of Contemporary Art. Before the world reopens and the show continues its journey, we interview Bernard Lumpkin and Matt Wycoff about the decisions behind the show and its organisation.

A: Bernard, you’ve been unofficially dubbed as a “black art ambassador” – having collected some of the biggest names in the last two decades, including LaToya Ruby-Fazier and Kara Walker. Where did your collection begin and what the your ethos / driving force behind it?

BL: My mission-driven approach to collecting has been shaped by three different things – my previous career as a news producer at MTV; my parents, who taught me the importance of education and civic engagement; and my mixed ethnic and racial background. My father was African-American and my mother was a Sephardic Jew from Morocco. So I’m interested in the questions artists of color are asking about race, history, and what it means to be American today. Another driving force for me is my conviction that patrons need to support the institutions (museums and not-for-profits) that support the artists they’re passionate about. Hence, my service on boards or committees at The Studio Museum, MoMA, the Whitney, and the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture.

A: How far do you believe that collectors have a responsibility to “advocate and educate”? How might collectors be part of the wider conversation of representation and inclusion?

BL: Leaders build consensus and galvanize support. So a lot of what I do involves cultivating other patrons and creating networks to connect artists with museums and galleries. I’m not alone in this effort: I stand on the shoulders of collectors and patrons who came before me. In fact, there’s a “hidden history,” as it were, of collectors in America who supported black artists when galleries and museums didn’t. This lineage dates back to people like Alain Locke, the patron saint of the Harlem Renaissance, and includes more recently people like Peggy Cooper Cafritz, Leah Chase, and Dr. Leon Banks. These individuals went far beyond what most collectors do. They didn’t just acquire art; they preserved it, passed it down, and made sure it was shown and seen. They took on a custodial role, stewarding artists’ careers so that their work would be enjoyed by future generations. I’ve always felt like I’m working within the lineage of these patron-champions. And hopefully I’m also showing the way for people who will come after me too.

A: The show, Young, Gifted and Black delves into the collection – its first standalone public exhibition – curated by Antwaun Sargent and Matt Wycoff. How does the show tie into Sargent’s previous work with The New Black Vanguard? Where did you meet and when did you start working together?

BL: Antwaun’s previous work as a writer and critic had a huge role in shaping his work on this project, both as co-curator of the traveling exhibition and editor of the forthcoming book “Young Gifted and Black: A New Generation of Artists” (forthcoming DAP July 2020). I had read his articles and interviews with black artists, how he was exploring the conversations that were happening between art, fashion, and photography. I’ve always been interested in cross-disciplinary approaches like that. So I knew his work, and then – since we’re both interested in many of the same artists – I kept running into him at parties and openings. And we would talk. I remember thinking to myself, this is someone I should be working with.

A: How do you balance the collection of emerging and established artists? How important is it to support both?

BL: I often use a sports analogy to illustrate the way I see my role as a patron of new and emerging artists. I ran track in high school, and one of my events was the mile relay: four runners each running a quarter mile. You run your quarter, and then you pass the baton. It’s the same thing when you’re a patron. You do your part, and then you let others do theirs. Artists need champions at every stage at their career. My focus is the early stage, especially the transition between art school and an art profession. How can I help artists navigate that transition? How can I connect them with the people and places who will support them and nurture their work? Playing a role in an artist’s success: for me, that’s the work and the reward of being a collector.

The older-generation artists are an essential part of the story I’m telling with this collection. Any figurative painter working today has to acknowledge the influence of people like Kerry James Marshall and Alice Neel. Similarly, how can you talk about contemporary abstraction without mentioning Norman Lewis, Howardeena Pindell, Sam Gilliam, Alma Thomas? Of course everyone is an innovator, and ever generation writes its own chapter, but that doesn’t mean that artists work in a vacuum. And I want the collection to show the importance of this intergenerational dialogue. So while my focus is on younger, emerging artists, I also acquire selected important works by older, more established artists. The mixture of the two gives the collection texture and makes it more dynamic.

A: Matt, how does the show offer a kind of timeline – artists that have “paved the way” and those emerging today?

MW: We wanted the exhibition to foreground an emerging generation of artists of African descent, whilst also presenting standard bearers from an older, more established, generation as both lineage and foil for the younger. To that end, our loose rule was to have 60 per cent of the work represented made by younger artists (under 40), and 40 per cent made by older artists (over 40). But the answer to this question is really in the details of the selections and the installations. For example, in the first exhibition we paired a Kara Walker cutout silhouette with a Sable Elyse Smith colouring book painting. In that pairing, you have two black female artists from different generations wrestling directly with issues of race who are using strategies that force the viewer to confront the content in new ways. Walker’s black and white cut outs reference 19thcentury shadow portraiture as well as children’s book illustrations, but depict a child pulling/playing with the entrails of a pig; and Smith uses the style of children’s coloring books to depict a family’s conjugal visit at a prison facility. Pairing these two artists highlights a well-known older artist (Walker) borrowing a startling visual language to address issues of race, and a younger artist (Smith) adapting that approach in her own way. These sorts of interactions between the older and younger artists abound in the exhibition, and represent both the continuity and innovation occurring throughout.

A: Are there similar threads / themes in the show? Are there recurring topics or subject matters?

MW: In our initial conversations about curating an exhibition from the Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection, Antwaun and I settled on separating the works into four categories: Portraiture, Materiality, Colour, and Blackness. One of the most exciting aspects of the exhibition for me is how, once parsed out into these categories, the works interact and overlap between each section. For example, in the current exhibition at Lehman College we have six large-scale paintings hanging salon style on the galley’s largest wall. These works deal with a range of subject matter, but all use color in very dramatic and exciting ways. Immediately adjacent to these paintings is a painting by Alteronce Gumby that appears to be a black color field painting, but which is actually a grid of Gumby figures from the 1950s and 1960s era cartoon rendered primarily in black, but with highlights of lush dark green throughout. Here you have a really interesting conversation about “color” and “blackness” – artists using explosive color to represent different aspects of the black experience immediately adjacent to an artist (Gumby) using the color black to have a very painterly, but also a humorous personal conversation about both color and identity.

A: What are some of your favourite artworks from the collection / show?

MW: I wouldn’t say that I have favourite individual works, but some the works I spent the most time with are landscape paintings of Cy Gavin. I am a huge fan of American landscape paintings from Fredric Church and the Hudson River School, to Horace Pippin, Milton Avery and Lois Dodd. I’m also a lover of hiking and travel that takes me into nature, so confronting Cy Gavin’s paintings was a real revelation for me because I realized very viscerally through his work that the land and the landscape means different things to different people. That is a startling revelation. As a lover of landscape, as well as art that deals with nature and the land, delving into Gavin’s work has made my subsequent experiences of both so much richer, more complicated, and compelling.

Credits:

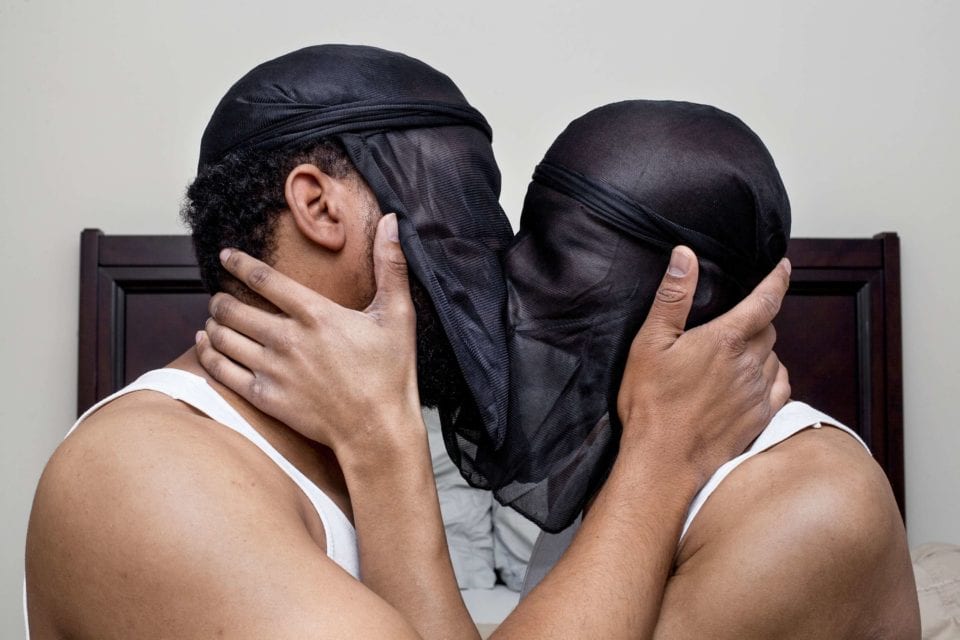

1. D’Angelo Lovell Williams, The Lovers, 2017. Pigment print, 20 x 30 in. © D’Angelo Lovell Williams, Courtesy of the artist and Higher Pictures.

2. Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Dark Room Mirror Study (0x5A1531), 2017. Archival pigment print, 51 x 34 in. © Paul Mpagi Sepuya, courtesy of the artist and team (gallery, inc.), New York.