The earliest pilotless vehicles were developed in Britain and the USA during WWI. Imperial War Museum, London, traces the first test flight back to March 1917, and the use of the word “drone” is attributed to the inter-war period, around 1935. Since then, unmanned aerial technologies have been developed for array of non-military purposes: from photography and filming to delivering goods, monitoring weather conditions, surveillance, search and rescue missions and more. They are becoming increasingly popular as an alternative entertainment choice, replacing fireworks to create impressive and hypnotising light displays considered cleaner, quieter and safer than the traditional pyrotechnic explosive.

The influence between art and science, as always, runs both ways. Designers are now harnessing the creative potential of drones to push research and innovation forward. In October 2023, Dutch studio DRIFT staged a large-scale, 1,000-drone performance over New York’s Central Park, simulating an illuminated flock of starlings. Titled Franchise Freedom, it’s based on a biological algorithm from over 10 years’ research into flight behaviour. The studio is dedicated to stretching the boundaries between nature and technology, and reestablishing connections between people and the natural world. Franchise Freedom is a testament to the power of interdisciplinarity, and what can be achieved when the seemingly disparate worlds of engineering, art and ornithology collide.

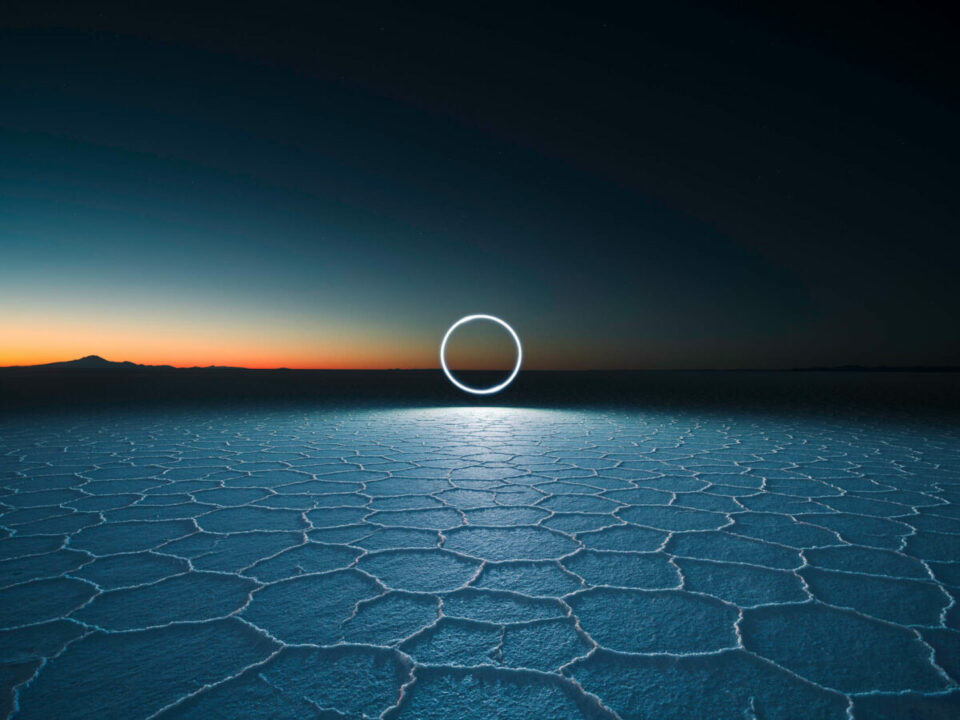

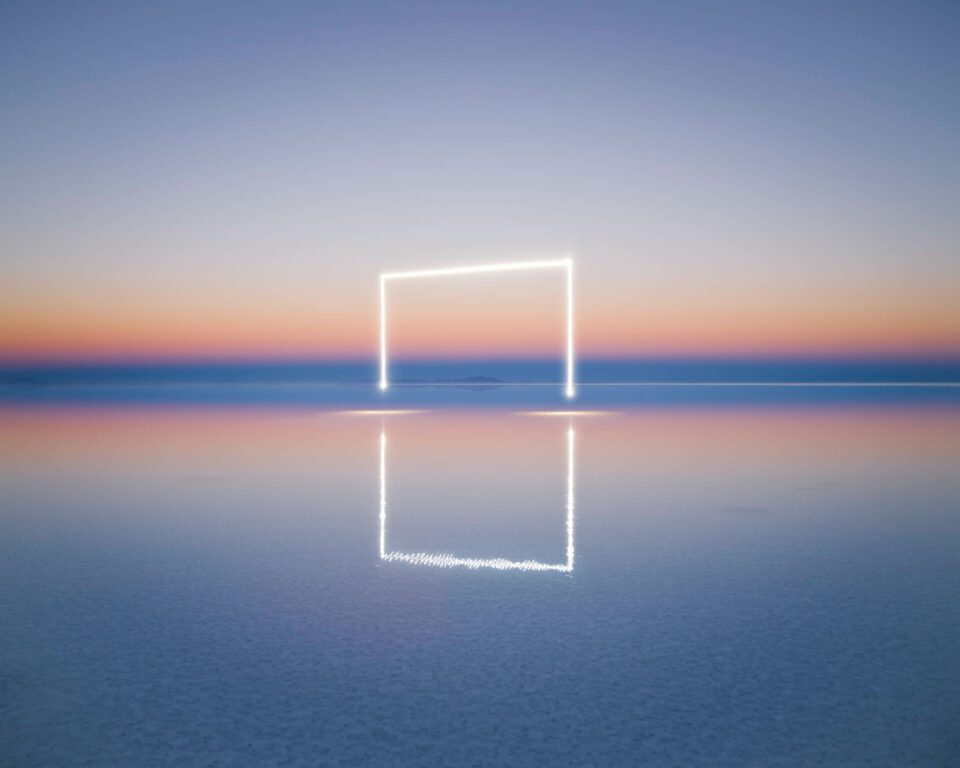

The reach of this burgeoning technology goes beyond performance and public art. Reuben Wu (b. 1975), a previous Aesthetica Art Prize finalist, is applying the same ethos to photography. He is a notable name, recognised not only for his contribution to electronic band Ladytron, but for crafting mesmeric landscape shots featuring glowing geometric shapes. Halos – created by light-carrying drones and long exposures – encircle high peaks, emerge from canyons and hover over open water. Now, as a National Geographic Photographer with clients including Apple, Audi, Samsung and Volkswagen, he’s interested in how we can harness abstract concepts of time and space to help tell compelling stories about our world. He has visited various remote locations across the globe, including glaciers, deserts, salt flats and mountain ranges, where he sets up each shot with precision. At a time in which it can be hard to decipher “real” from “artificial”, Wu shows us what it is possible to create in real life and on location, using post-production skills rather than AI generation prompts or 3D rendering. We speak to the artist about his practice, touching upon the relationship between documentary and fine art, and tracing his influences back to Harold “Doc” Edgerton (1903-1990) – the first person to “stop time” by inventing the strobe light in the early 1930s.

A: Where did your journey behind the camera begin? When did you first use a drone, and where are you now?

RW: My path into photography was indirect. I only found my passion for it after I started touring the world with my electronic band, Ladytron, which formed in Liverpool in 1999. Image-making was an alternative creative outlet that came from exploring new countries. It snowballed, and I went from documenting my surroundings to immersing myself into alternative processes such as film, Polaroid and infrared photography. I’ve held on to the notion of experimentation with technology and began to attach lights to drones in 2015. Now, my work is in the permanent collections of Guggenheim Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and MoMA.

A: Where did the ideas for Aeroglyphs and Lux Noctis come from? They seem to be quite ahead of their time.

RW: Lux Noctis draws on classic landscape imagery and is inspired by 19th century romantic painters like Caspar David Friedrich, John Constable and J. M. W. Turner, but it uses aerial light to create a completely new look and feel. It’s also influenced by planetary exploration, chiaroscuro painting and science fiction. The idea was to depict landscapes unbound by time and space. I initially used this lighting technique for a project I was working on with a car. It was through this experimentation that I realised how well the approach could work for documenting landscape. I saw how interesting the light trails left by the drone under long exposure were – like a form of environmental land art. I leaned into that and put the focus on the shape of the light forms and how they illuminated the surrounding environment. I called these temporary geometries – over land, water and sky – Aeroglyphs.

A: Tell us about some of the places you have visited along the way. Is there anywhere that really stands out?

RW: I’ve photographed in several remote and extreme locations. A place I keep coming back to is Utah. It’s somewhere I used to dream about as a kid growing up in the UK. I was finally able to experience its deserts – the Mojave, Great Basin and Great Salt Lake – fully once I moved to the USA 10 years ago. Bolivia is another location that stands out. I first visited in 2019, and it’s where I made the Field of Infinity series during a week-long road trip. The Salar de Uyuni in the southwest is one of the most sublime – and coldest – places I’ve ever experienced. It’s the world’s largest salt flat, stretching more than 4,050 square miles, and was formed out of huge prehistoric lakes that evaporated a very long time ago.

A: Your pictures are so magical – one might be forgiven for thinking they are made with digital tools like Photoshop or 3D rendering. Can you walk us through the process of making one of your images, from start to finish?

RW: Each piece takes a few hours, at least. I start the day by scouting the location and deciding on my composition, camera position and angle, and lock the tripod in position. I wait until the light starts getting good, usually just before sunset, and begin shooting select frames as it gets darker until nightfall. Once it is completely dark, I capture long exposures using artificial light. Sometimes I’ll send up a drone, other times the source is handheld, or I’ll use various other light painting tools. I see this process as akin to traditional brushstrokes, where I’m drawing lines of light that are at very specific angles to the surrounding environment. Texture and contrast are also elements I like to explore whilst on location.

A: What is the role of post-production and editing? How do you make these compositions look so perfect and crisp?

RW: The post-production phase is all about creating the final work. It involves layering and painting multiple exposures on top of one another to create the vision I had in mind. It’s a very important stage. The shoot is pretty unrestrained and playful, whereas post-production is a more disciplined task where I’m sharply focused on creating the story I want to tell.

A: You’re a collaborator of National Geographic, a leading publication that is best known for its science and environment stories, but you’ve also been published by Artsy, Colossal and Designboom. Are art and reportage separate genres, or do you think they should converge?

RW: National Geographic is not just a champion of factual science and journalism, it also stands for photography and using technology to tell visual stories better. As someone who is both a National Geographic photographer and a visual artist, I’m very careful in being transparent about how I make images for the publication and its audience. I know that my work can seem otherworldly, and even digitally rendered to some eyes, but there is a realness in my images that simply can’t be created in Photoshop or 3D modelling. My aim has always been to show the familiar under an unfamiliar light, and I feel that is part of National Geographic’s core tenet, too.

A: Is there value in these worlds colliding? What can an “artistic” point of view bring to traditional documentary? Is there a project you have worked on that embodies this?

RW: I would argue that all the pictures in National Geographic are made from an artistic perspective. All I am doing is using old tools – light, shadow, colour, contrast, texture – in a new way. We are overwhelmed every day by beautiful, yet familiar, images. I imagine these scenes transformed into undiscovered landscapes, which renew our perceptions of the world. The goal is to open people’s eyes to a subject and maybe change the way they feel about it. It all comes down to what I feel is the focus of the picture, what it is drawing attention to and how it helps to tell a part of a bigger story. In 2021, for example, I was commissioned to photograph 5,000 year-old Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England. The formation is one of the most photographed landmarks in the world, and I wanted to bring new meaning to this old and storied subject.

A: Technology is influencing art in new and interesting ways all the time, from immersive installations to controversial AI generated content. How do you see that relationship developing going forward? Is it exciting, or do you have any concern for the future of human creativity?

RW: The inexorable development of technology is something that certainly inspires me. It’s also pushing the boundaries of art. I use digital tools to inspire new ideas that, without the technology, I simply would not have had. However, that said, I think these kinds of tools should always be in service to the story, otherwise it is just a demo. Art and technology merge together best when the human factor is so entwined in the process that you cannot deny the value of either element.

A: Are there any visual artists, filmmakers or photographers whom you particularly admire – past or present? What do you find inspiring about them or their artwork?

RW: Doc Edgerton was a pioneer of the strobe flash in the 1930s, an innovator who allowed us to “stop time” and capture what the unaided eye could not see. The cinematography of Andrei Tarkovsky is also a big inspiration, as are the surreal worlds of David Lynch. In photography, Evgenia Arbugaeva combines documentary and fine art to record life in the Russian Arctic, whilst Gregory Crewdson’s filmic works are endlessly compelling. Helena Sarin, James Turrell, Jeff Frost, Michael Wolf, Neil Krug and Taryn Simon, to name just a few, are also up there on my long list of creative influences.

Further details of Reuben Wu’s forthcoming projects can be found online.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image credits:

All images: Reuben Wu, from Field of Infinity (2019). Image courtesy of the artist.