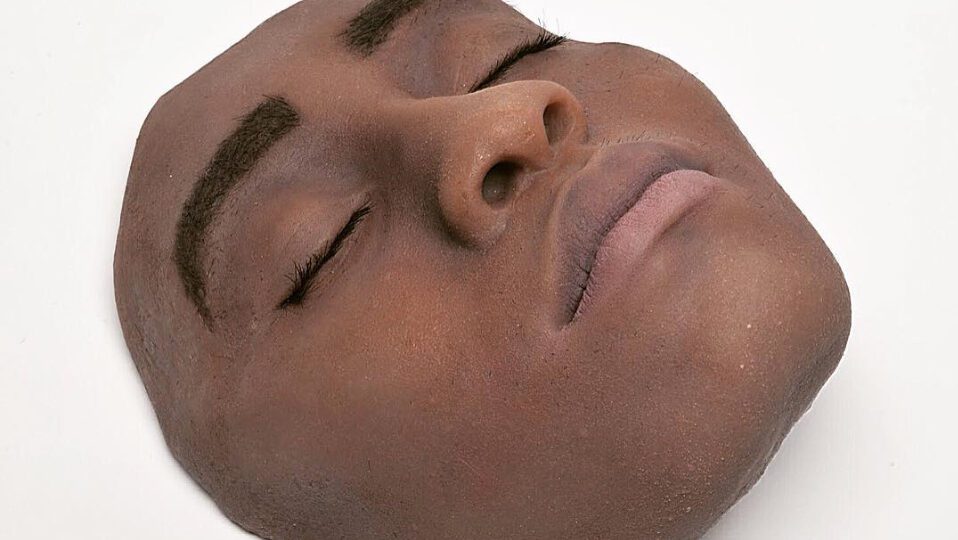

Rayvenn Shaleigha D’Clarke’s practice stems from a single observation: that “monuments and public sculptures are never of women of colour.” The artist’s work challenges historical portrayals of Black anatomy by constructing the Black body with precision and dignity. Untitled (2016), was shortlisted for the 2025 Aesthetica Art Prize. The silicone sculpture emerged from a three-month process dedicated to capturing anatomical detail, nuance and presence. D’Clark reclaims agency over representation, pushing against colonial narratives that sought to erase or distort Black identity. Since the opening of the Art Prize, D’Clark launched the very first public sculpture representing postpartum. Mother Vérité, located outside of the Lindo Wing of St Mary’s Hospital, London, is a celebration of the unfiltered reality of recovery and the raw, often unseen, realities of new parenthood. The artist’s sculptures are not only a physical form – they are a political statement and a demand to be seen in full. Aesthetica spoke to D’Clark about her creative process and what it means to reclaim the Black body.

A: How did you start working as an artist?

RD: I have always seen myself as a creative person, long before I ever called myself an “artist.” My parents still joke that I was never without a pen and paper, always drawing and making. That impulse to create has been there for as long as I can remember. It wasn’t until my undergraduate studies that I began to develop my practice, and saw making art as a deeply personal, social and political act. During my degree, I became increasingly interested in sculpture, particularly as a way to reimagine the human form, and in how Black bodies are positioned as sites of labour. I also explored how technology could be a tool for positive reframing. After graduating, I started exhibiting in group shows, developing a language around digital materiality and the politics of representation (body politić). Early shows at Cob Gallery and 198 CA&L opened up new conversations and opportunities for collaboration. Later, these expanded into more institutional and international contexts in Europe and the US. Curation also became a natural extension of my research, prompting me to question visibility and power within cultural institutions. Projects at Nunnery Gallery, V&A, and Guts Gallery became sites for considering how Black and brown bodies, in particular, are made legible within institutional frameworks. In taking part in exhibitions, talks and panels at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Royal Society of Sculptors, and the London Design Biennale, I have come to see sculpture and public art as a way to keep asking who gets visibility, and why.

A: Can you walk us through the three-month process of creating your shortlisted sculpture?

RD: My practice always begins from a place of curiosity – a kind of slow, personal research that often turns into obsession. For Untitled, I was thinking about what it means to make an object without reference or categorisation, something that exists in-between: part figure, part abstraction, somewhere between technology and flesh. I spent a few weeks reading, sketching and testing materials to develop a framework before I began making. The technical process is equally critical. Working with a live model, I built the first mould using silicone gel, plaster bandages and lubricant, which becomes a strange choreography between body and material. It rarely works on the first attempt, so I remake and refine until the mould feels right, then move on to secondary casts in clay and liquid plastic, reverse-engineering the form until the surface holds the detail I need. Colour is the most challenging and political part. I spend three to four weeks mixing silicone pigments and testing hundreds of swatches to create a brown tone that industry palettes rarely support. Each attempt became a microstudy in chromatic politics. When I feel that it is right, I pour, let the mould cure, and then begin to bring life back into the piece by adding hair, pigment, makeup and texture. These gestures aren’t just aesthetic; they’re about presence, about translating the body into something material, and insisting that it remains seen. The process as a whole sits between tactile, methodical and obsessive, but relies on translation: from body, to material, to concept.

A: How does your art converse with, or resist, traditions that have excluded or objectified Black bodies?

RD: My work engages in a critical dialogue with the western sculptural canon, aiming to reconfigure its logic. Traditional figurative sculpture has long operated as a means of elevation, idealising its subjects through form and material. The use of marble, with its pristine whiteness, is not neutral, and it encodes a racial hierarchy that equates purity with whiteness and permanence with power. In my practice, I seek to both occupy and subvert that space. By centring brown bodies within the language of classical form, I am not merely inserting them into an existing framework, but fundamentally interrogating the framework itself. The work questions what happens to viewership and engagement with an object when the central figure is a marginalised body. Equally, I am interested in the oscillation between visibility and absence. Some more recent works remove colour entirely, rendering the body in monochrome as an open act of refusal to offer markers about the sitters’ background. This withdrawal from chromatic identity becomes a conceptual strategy, dislodging the viewer’s reliance on (skin) colour as the primary interpretive lens. In doing so, the work destabilises the aesthetic hierarchies inherited from classical sculpture.

A: In what ways do you see your work reclaiming and recontextualising the Black body?

RD: The reclamation of the Black body within my practice is both formal and philosophical. Historically, the Black form has been rendered peripheral, positioned as object rather than subject; as spectacle rather than self. My work insists upon the centrality of Black and brown bodies, demonstrating their autonomy and ordinariness. Through monochromatism, scale, materiality and stillness, I attempt to normalise the Black figure within sculptural space, not as an exception but as standard. Recontextualisation, for me, involves abstraction. By removing narrative markers and stripping away overt cultural identifiers, I aim to create a space where the body can be seen anew, detached from the histories of colonial gaze. It becomes an invitation to encounter Blackness not through the lens of trauma or fetishisation, but through form, texture and a highly technological methodology and, ultimately, presence. This act of centring is, for me, political and deeply personal. It is about reclaiming the Black body as a site of multiplicity – a body that holds both vulnerability and power, hypervisibility and erasure.

A: How do you hope audiences respond to the piece?

RD: I hope that audiences have sustained engagement with Untitled. That they can encounter the work slowly, and sit with its quietness, its material ambiguity. Curiosity, for me, is a radical mode of looking; it suggests an openness to unlearning, to re-seeing. Ideally, the work interrupts familiar ways of viewing the body and asks: What does it mean to look without narration? To encounter form without the need to categorise it? Ultimately, Untitled aims to occupy a liminal space: between realism and abstraction, self and object, representation and refusal. It is less about providing answers for audiences and more about holding the question of how bodies like mine come to exist, persist, and are seen within the sculptural canon.

The Aesthetica Art Prize Exhibition 2025 is at York Art Gallery until 25 January.

rayvenn-dclark.com | yorkartgallery.org.uk

Words: Emma Jacob & Rayvenn D’Clark

Find out more about the Aesthetica Art Prize 2025 Shortlist here.

Image Credits:

All images courtesy Rayvenn Shaleigha D’Clark.