A famous critique of Jean-François Lyotard’s brassy “I define postmodern as incredulity toward meta-narratives” is that, if you go in for his postmodernism, you have to be incredulous towards this statement as well. You also have to distrust the meta-narrative of postmodernism, and have to distrust the “have to” part, then not take that distrust for granted in turn, and so on and backwards. This quickly becomes recursive, the mental equivalent of looking in a mirror at a mirror behind you. So what starts out as a defence against monolithic and dubiously agenda-driven claims to power becomes paralysing quickly – what possible action can you take when everything triggers an endless chain of distrust? For artist Mary Kelly, whose career has been devoted to a narrative-based analysis of Feminism and post-modernism, flitting between the personal and the theoretical as in her famous Post-Partum Document (1973–1979), this is of crucial importance. How much incredulity, or rather self-incredulity, is needed, is healthy – even towards the narratives of Feminism and post-modernism themselves?

On the passage of a Few People through a Rather Brief Period of Time is a careful tending to this, at a point when she feels as though her “era” has ended. Hers is the generation of people born during World War II – those who inherited the spirit of the fight for a just world by being born into a ruined one. From this, they charted a brave course in the fight for civil rights, Feminism, and the hope of a socialist utopia. It is logical therefore that Circa 1968 (2004) is the lynchpin of this exhibition and the point of focus, straight ahead as you walk in, around which all else hangs. Made for the 2004 Whitney Biennale, it uses an image taken by Jean-Pierre Rey from Life magazine, 1968, in which Caroline de Bendern is on the shoulders of Jean-Jacques Lebel, the leader of the student occupation in Paris, hoisting the Vietnamese flag in a zeal reminiscent of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. Light noise is projected onto this image, in a way re-animating it but perhaps not quite enough.

While this is a call to those who were not alive to see or feel this moment, it is also striking how unreal it seems, as though the piece doesn’t quite believe in itself entirely. Delacroix’s own revolutionary zeal has faded into art history, and it is noticeable how the image from Life has become a model for current protests despite being frozen in time. Mary Kelly quotes Guy Debord: “That which was directly lived reappears frozen in the distance, fit into the tastes and illusions of the era carried away with it.” How do we access this moment as it, from our perspective, flickers in the light noise and the era that has elapsed since? Is this moment important? At the same time it is only “circa” something. It is an approximation. Some things are passed down: passion, a style, a cause; but even if the past does have answers, they are hard to see through the interference, and remembering is an act of making, not of re-making. Here comes the necessary incredulousness.

Because actually, although this photograph is famous, the moment it features is fairly trivial, just as it is in Liberty Leading the People. A flag is waved, a woman is on a man’s shoulders, a figure surmounts a pile of bodies. These aren’t moments the world changed, but they are something more, ghostly, and potentially more insidious. Although they are forgettable moments in the fluxes of life, they have become allegories rather than just a few people passing through a rather brief period of time, and an allegory is a type of manipulable conclusion. They have become impersonal, like the marines on Iwo Jima in Life, April, 1945 (2014), or the rioter raising his fist “in defiance and rage” as tear gas billows around him in Rhodesia in 7 Days, February, 1972 (2014). Kelly’s work tries to give them back their status as people, though time has lost their personality.

Alderney Street, 1973 (2014) shows why. It is based on a photo of the Alderney Street commune in Pimlico, which ran from 1970–1976 and at which Kelly lived. It shows that action is carried out by a few people passing through, who touch and are touched by historical movement and new ideas, yet barely appear at all and soon fade into the hive of the event, as in 7 Days, March, 1972 (2014). Two unidentified women are on the March front cover, but the issue features an interview with Simone De Beauvoir, who declared “Today, I’ve changed. I’ve really become a feminist”, which in turn enraptured and inspired Kelly to independent struggle for female emancipation.

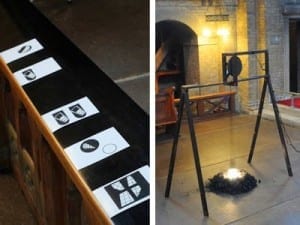

Although this show is about 1960s and 1970s political activism, friendship, time and awakening, there is no sepia tinting or nostalgia involved. To be nostalgic is to look back on time as lost, but for Kelly it accumulates, sometimes obscures, sometimes passing things of value on to the next generation, things perhaps to be used. This is even evident in her choice of material: tumble dryer lint, accumulated over many months and washing cycles, then printed onto the paper in layers. The more dense the lint, the more saturated the colour area, like a more-vivid memory.

In all the lint built up since 1968, or even 1830, Kelly lays down her one piece about modern conflict – she is modestly nervous about telling things to the internet age. It is based on a photo by Peter MacDiarmid of protesters at a rally in Tahrir Square, Egypt, 23 November 2011. They are wearing gas masks, and one holds a camera phone in one of the three single arms raised in this exhibition. People are still meeting history and the lint keeps falling. The conundrum doesn’t go away. It is necessary to remain incredulous but you have to believe in something, and Kelly’s work seems to tread that line wonderfully. Not by supporting the authoritative answer of a revolution or the meta-narratives behind them, but by spurring us on to the constant questioning of protest.

Mary Kelly: On the Passage of a Few People through a Rather Brief Period of Time, until 4 October, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, 6 Heddon Street, London, W1B 4BT.

Jack Castle

Credits

1. Mary Kelly, Tahrir, 2014, compressed lint, framed, 114.3 cm x 175.9 cm, 45 in x 69.25 in H6682 7/13.