What happens when a “typology,” a principle once used to categorise and study ferns and flowers, is turned toward the human gaze, the face of a nation, or the geometry of an industrial water tower? In a world where the image is omnipresent and meaning diluted, Typologien: Photography in 20th-Century Germany offers a pause. Opening at Fondazione Prada in Milan, this sprawling and thoughtful exhibition – curated by Susanne Pfeffer – unearths and reanimates the typological impulse in German photography, unfolding it across time, space and subject matter.

Presented in the Podium, the foundation’s central architectural space, Typologien resists the obvious path of chronology. Instead, it invites visitors into a visual dialogue defined by repetition, resemblance and rupture. Over 600 works by 25 artists are displayed in a deliberately disorienting, non-linear installation – “a system of suspended walls,” as the curators describe, designed to disrupt and recombine perspectives.

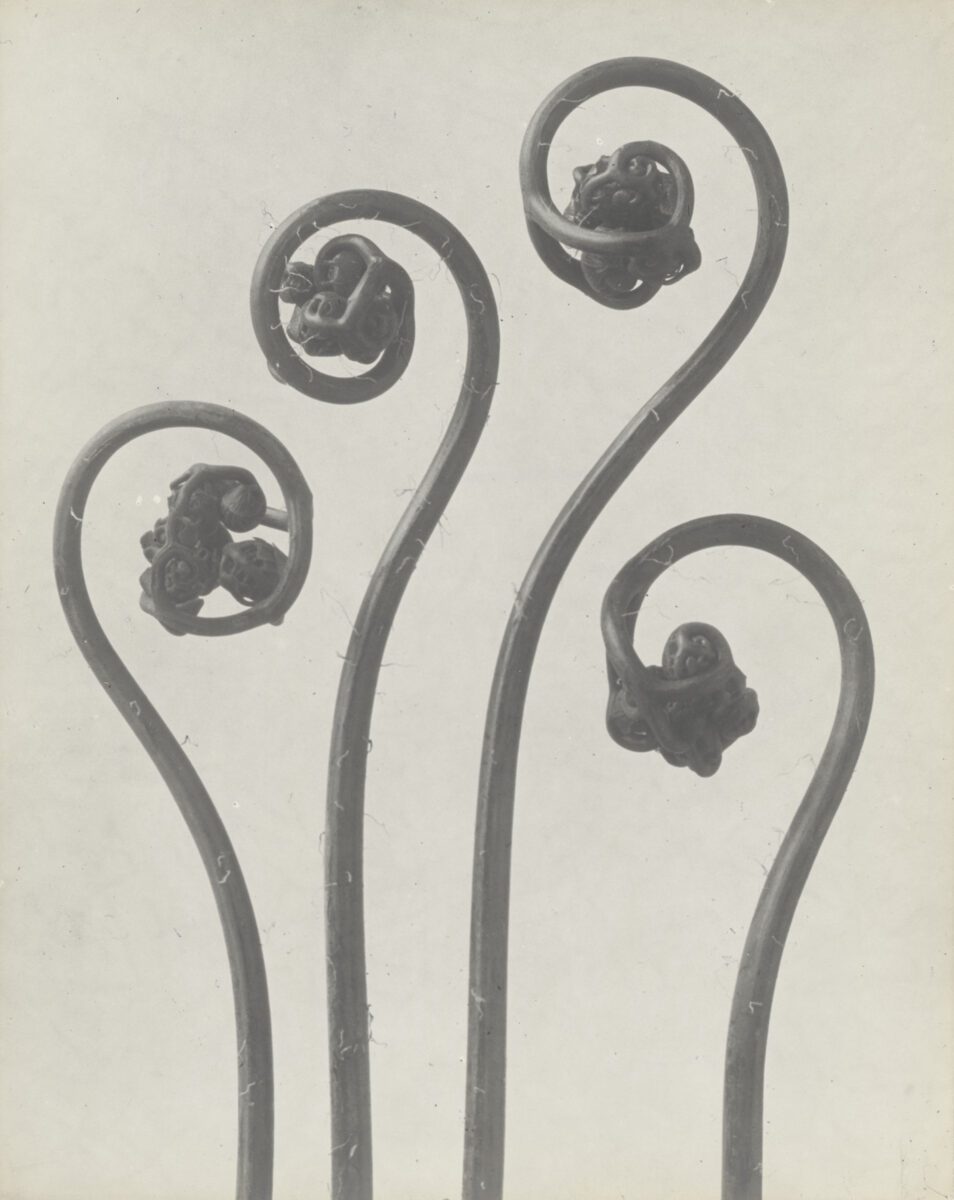

“This isn’t just about looking,” Pfeffer explains. “It’s about seeing through comparison. Only through juxtaposition and direct comparison is it possible to find out what is individual and what is universal, what is normative or real.” Her words echo across the exhibition’s conceptual architecture: a quietly radical approach to the photographic archive. The origins of typology in photography are traced back to Karl Blossfeldt’s botanical studies – detailed black-and-white portraits of plants that treat the organic like the mechanical. These works, emerging from the Weimar Republic’s Neue Sachlichkeit movement, appear almost futuristic today: alien ferns, frozen in time, poised in symmetry.

August Sander’s Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time) from 1929 offers a counterpoint, applying the same rigid classification to human society. With subjects arranged by profession, class, and role, Sander’s portraits construct a sociological archive that is both precise and profoundly human. Walter Benjamin famously called it a “training atlas of physiognomic perception,” and in Pfeffer’s hands, it becomes foundational: not just as history, but as a provocation. “The unique, the individual, seems to have been absorbed into a global mass,” Pfeffer reflects. “And yet this is precisely when it seems important – to artists – to take a closer look.”

Bernd and Hilla Becher answered that call in the late 1950s with their now-iconic typologies of industrial structures: gas tanks, blast furnaces and grain silos. Shot head-on and framed identically, their works operate almost like taxonomies of ruins. “The information we want to provide is only created through the sequence,” they wrote. “Through the juxtaposition of similar or different objects with the same function.” Their approach not only influenced generations of conceptual artists but defined a German photographic sensibility that remains potent today.

Indeed, many of their students – Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth – are present in Typologien, each refracting the Bechers’ influence through their own evolving practices. Gursky’s monumental images, Höfer’s hushed interiors, Struth’s urban grids: all continue the typological mission while questioning its limits.

This tension – between the systematic and the subversive – courses through the exhibition. Hans-Peter Feldmann’s quiet catalogues of ordinary things, like Alle Kleider einer Frau (All the Clothes of a Woman, 1975), challenge our hierarchies of value. “With his typologies,” says Pfeffer, “he emphasised the equal value of all photographs, their image sources and motifs, and underscored the de-hierarchisation inherent in every typology.” Gerhard Richter’s Atlas takes this a step further. A sprawling “private album” composed of found images, historical fragments, and personal snapshots, Atlas resists order while imitating its appearance. Typology here is not a system but a mirror – distorted, overwhelming, and deeply unsettling.

That slippage between categorisation and chaos is where Typologien finds its most contemporary relevance. In an era shaped by the algorithm, where digital platforms categorize and recirculate imagery at speed, the exhibition urges us to slow down. Isa Genzken’s Hi-Fi series, composed of Japanese stereo ads, and her Ohr (Ear) portraits – close-ups of women’s ears photographed on the streets of New York – mock the idea of a single, stable visual taxonomy. What does it mean to organize bodies, ears, or even stereo systems? What gets lost in the act of naming? “When the present seems to have abandoned the future,” Pfeffer says, “we need to observe the past more closely. When everything seems to be shouting at you… it is important to take a quiet pause.” That ethos radiates through Typologien – not as nostalgia, but as necessity.

Aesthetica has long championed exhibitions that bridge the historical and the contemporary, that explore how artistic form shapes social thought. Typologien does just that. It excavates a lineage of image-making deeply entwined with Germany’s turbulent modern history – from Weimar ambition to post-war reflection, from industrial rise to conceptual reinvention. And in doing so, it offers an understated yet vital proposition: that photography, at its most restrained, can be at its most radical.

As visitors exit the Podium, they are left not with a neat narrative but a mosaic of repetitions and subtle deviations. The cow, the fern, the water tower, the face. The typology is not a constraint – it’s a lens. And through it, we are invited to look again, and to look closer. Typologien: Photography in 20th-Century Germany is not just an exhibition – it’s an act of quiet resistance. In a world of visual excess, it returns to the image as observation, as evidence, as language. It reminds us, gently but urgently, that meaning often resides not in the extraordinary, but in the deliberate documentation of the everyday.

Typologien: Photography in 20th Century Germany is at Fondazione Prada, Milan, until 14 July 2025.

Words: Anna Müller

Image Credits:

1. Heinrich Riebesehl Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969 [ People in the Elevator , 20.11.1969] 1969 Kicken Berlin © Heinrich Riebesehl, by SIAE 2025

2. Thomas Ruff Porträt (Pia Stadtbäumer) 1988 MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST , Frankfurt © Thomas Ruff , by SIAE 2025 Photo by Axel Schneider, Frankfurt am Main

3. Thomas Ruff Porträt (Simone Buch) 1988 MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST , Frankfurt © Thomas Ruff , by SIAE 2025 Photo by Axel Schneider, Frankfurt am Main

4. Hilla Becher Studie eines Eichenblatts [Oak Leaf] 1965 © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne, 2025

5. Karl Blossfeldt Adiantum pedatum , h aarfarn , j unge, noch eingerollte Wedel [M aidenhair f ern , y oung, still curled fronds] n.d. Courtesy Berlin University of Arts, Archive – Karl Blossfeldt Collection in cooperation with Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne