Cerith Wyn Evans has spent decades bending light into language and sound into sculpture. Born in Wales and educated at Saint Martin’s School of Art and the Royal College of Art, he first emerged in the 1980s London experimental film scene before shifting his practice toward installations that make perception tangible. His works are ephemeral and monumental. Each piece asks us to consider how we inhabit time, how we move through space, and how light and sound shape our sense of being. Wyn Evans’ practice has always been deeply informed by music, literature and philosophy, weaving these disciplines into environments that feel both cerebral and sensory. It is this complexity and the insistence that thought and form are inseparable, which has made him one of the most significant contemporary artists working today.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s Cerith Wyn Evans …. in light of the visible marks the artist’s first major solo exhibition in the Asia-Pacific region. Running until 19 October 2025, it is a landmark presentation, both in scope and ambition. MCA Australia’s galleries become a luminous field, a “polyphonic immersion,” as Director Suzanne Cotter notes, “into a world of light, sound and pure poetry.” The museum’s location on Warrane/Sydney Harbour gives the exhibition an additional charge, with light and sound spilling beyond the walls and dissolving the boundary between institution and environment. In this context, Wyn Evans’ work feels not only exhibited but fully activated, engaging the city itself as collaborator.

MCA’s recent programming has set a precedent for staging transformative experiences. From its explorations of moving image and sound-based practices to its commitment to large-scale, immersive exhibitions, the institution has carved a reputation for giving artists space to operate at their most ambitious. Wyn Evans’ presentation pushes this further. The museum’s glass-lined galleries are alive with neon, sound and shifting light. The result is an exhibition that cannot be contained within its floor plan; it resonates outward, folding the city and its rhythms into the experience.

The centrepiece is Sydney Drift (2025), a major new neon installation that harnesses the shifting luminosity of Circular Quay. As daylight changes, so too does the work, transforming the MCA’s galleries into a constantly evolving environment. It breathes and recalibrates, drawing visitors into its slow, deliberate tempo. Alongside, Two Gravity Gongs (2025) extends this principle into sound, allowing the vibrations of the harbour precinct to reverberate through the museum’s architecture. Together, these pieces create an experience that collapses the division between inside and outside, art and world.

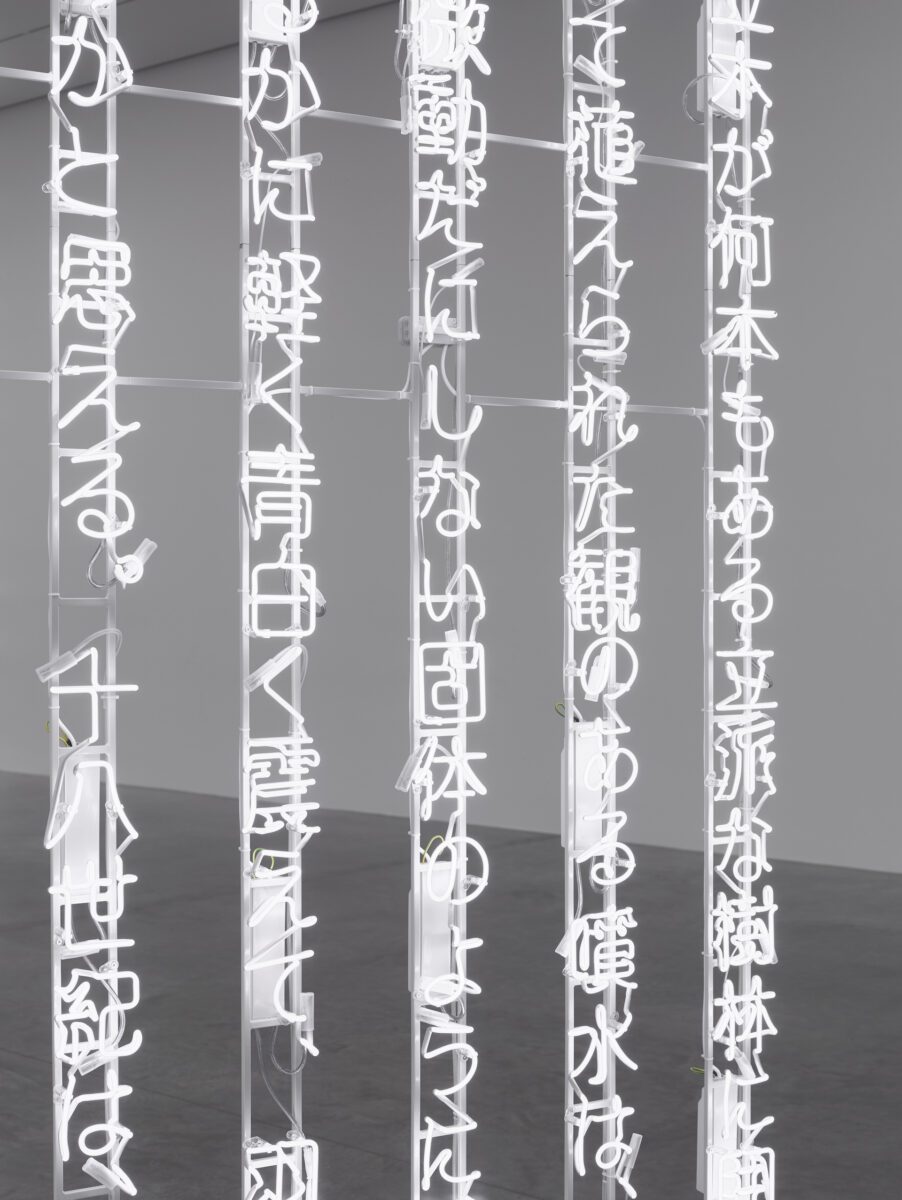

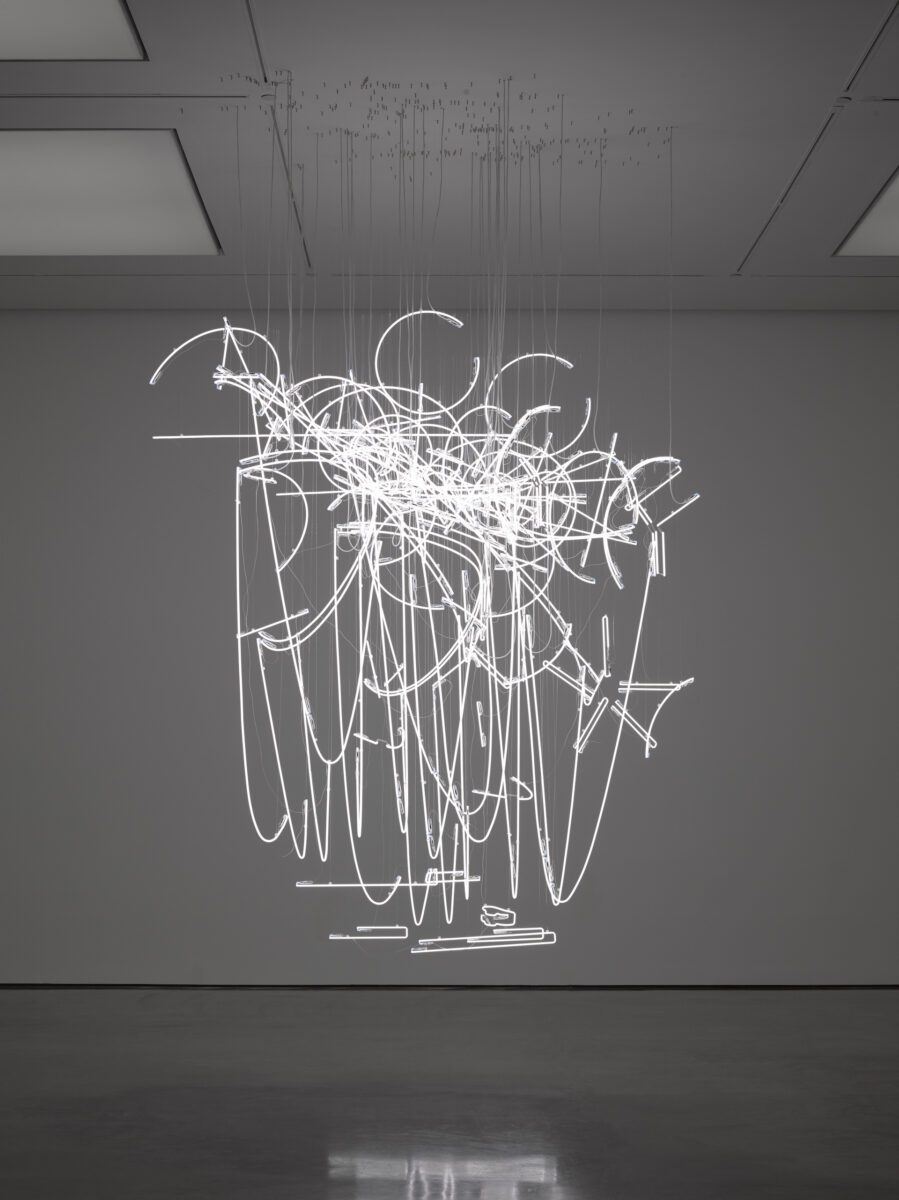

Other highlights include Composition for 37 Flutes (2018) – a sculpture that literally exhales sound – and F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N (2020), a monumental neon wall, three metres high and ten metres wide, that functions simultaneously as barrier and threshold. These works insist on movement: you do not simply look at them; you move with them, around them, through them. Similarly, the series Neon Forms (after Noh) (2015–ongoing) unfurls in the air like luminous calligraphy. Referencing the precision and elegance of Japanese Noh theatre, these gestural forms transform language into a spatial phenomenon, inviting viewers to navigate a choreography of light suspended in space.

“Conceived as if visitors were strolling through a garden,” writes curator Lara Strongman in the accompanying publication, “the exhibition invites a contemplative passage through space and time.” This metaphor of the garden is crucial. Like a garden, the show resists linearity; it is a space for wandering and return, where pathways cross and shift as light changes throughout the day. Works such as StarStarStar/Steer (2019) and phase shifts (after David Tudor) (2023) heighten this sense of fluidity, tracing invisible forces of sound and energy through the galleries and amplifying the exhibition’s atmosphere.

Wyn Evans’ practice sits in dialogue with a constellation of artists who also work with light and sound to interrogate perception. James Turrell’s skyspaces share his invitation to linger and look differently, yet Wyn Evans roots his work in a textual and musical density that gives it a different charge. Tracey Emin’s neons use language to speak in urgent, confessional tones, while Wyn Evans’ are architectural and spatial, less about emotion than structure and resonance. Even Ryoji Ikeda’s immersive sound-and-light environments, which translate data into pure sensory form, feel adjacent to Wyn Evans’ concerns, though his work is grounded less in systems and more in what he has called “the poetics of transmission.”

For the MCA, this exhibition represents more than a survey of an extraordinary career; it is a site-responsive dialogue with Sydney itself. Still Life (In course of arrangement…) (2025) incorporates native plants into the museum’s interior, merging the ecological with the sculptural and folding the outside world into the gallery. This emphasis on environment is not merely aesthetic. It signals an expanded understanding of sculpture as something porous, alive and attuned to the energies of its setting.

The exhibition’s public program extends this sensibility. Sonic improvisations by musicians from the Sydney Conservatorium ripple through the galleries, while The Catchment Dance Collective animates the space with movement, treating Wyn Evans’ installations as scores rather than static objects. Morning Tai Chi sessions on the Sculpture Terrace echo the exhibition’s themes of flow and duration, aligning the rhythms of the body with those of light and sound. These are not supplemental activities but essential components of an exhibition that understands art as experience rather than spectacle.

Ultimately, in light of the visible is less a retrospective than an invitation. It reasserts the vitality of sculpture not as an object to be circled but as an environment to be entered, inhabited and felt. In an era dominated by speed and instant image-making, Wyn Evans offers a counterpoint: works that demand time, patience and attention. In return, they sharpen our perception and remind us what it means to truly dwell – within art. Sydney will remember this exhibition not only for its scale but for its atmosphere: a charged field of light, sound, and thought that lingers long after you’ve left the gallery. As Cotter puts it, this is “a world of light, sound and pure poetry.” In Wyn Evans’ hands, that poetry is not metaphor. It is an experience.

Cerith Wyn Evans …. in light of the visible is at MCA Australia until 19 October.

Words: Simon Cartwright

Image Credits:

1. Cerith Wyn Evans, Sydney Drift, 2025. Installation view, Cerith Wyn Evans …. in light of the visible, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2025, image courtesy and © Cerith Wyn Evans, photograph: Hamish McIntosh.

2. Cerith Wyn Evans, F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N, 2020. White neon, 150 3/8 x 426 3/4 in. (382 x 1084 c m). © Cerith Wyn Evans. Photo © White Cube (Ollie Hammick).

3. Cerith Wyn Evans, F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N, 2020. White neon, 150 3/8 x 426 3/4 in. (382 x 1084 c m). © Cerith Wyn Evans. Photo © White Cube (Ollie Hammick).

4. Cerith Wyn Evans, Neon Forms (after Noh I), 2015. © Cerith Wyn Evans. Photo © White Cube (George Darrell).

5. Cerith Wyn Evans, Composition for 37 flutes, 2018. 37 crystal glass flutes, ‘ breathing ’ unit and valve system and plastic tubes, 187 13/16 x 139 3/4 x 118 1/8 in. (477 x 355 x 300 cm). Installation view, “…. the Illuminating Gas”, Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan, 31 October 2019 – 6 July 2020. © Cerith Wyn Evans. Photo © Agostino Osio. Courtesy the artist; White Cube and Pirelli Hangar Bicocca.