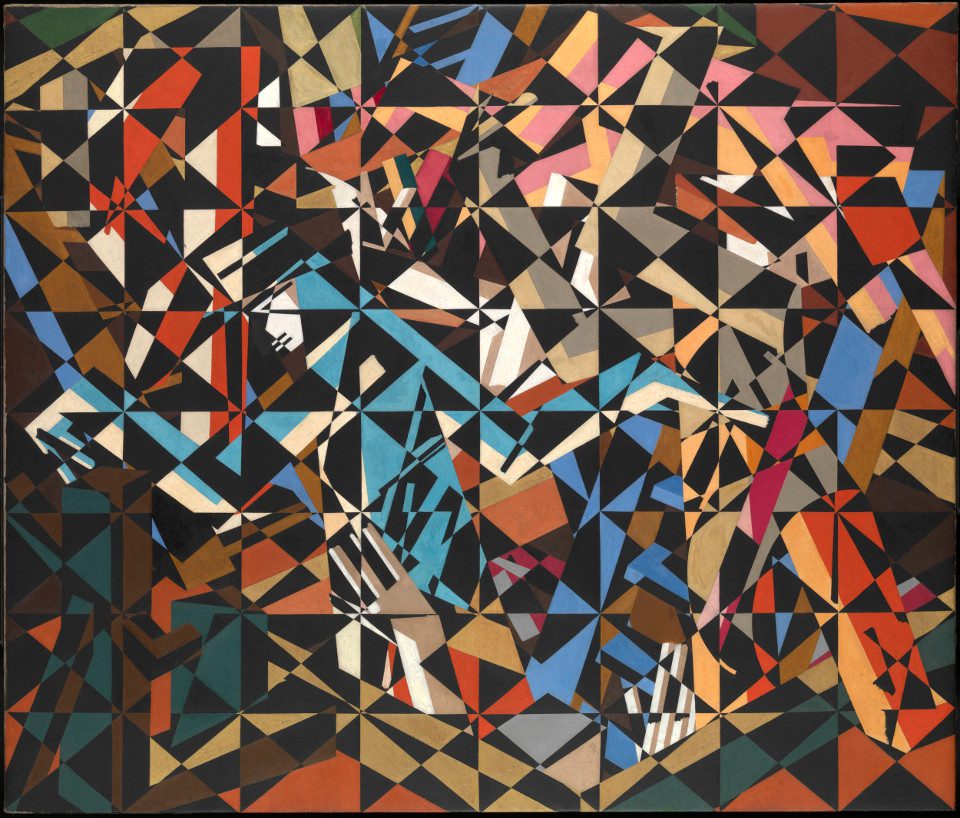

Winner of the IK Prize 2015, Tate Sensorium by creative agency Flying Object offers an immersive exploration of key works from Tate‘s prestigious art collection. Working with a team of collaborators and international ‘sense’ specialists, the collective seeks to reunite the act of seeing with the sensations of taste, touch, smell and hearing. Each of the four 20th century British paintings selected for the project (David Bomberg’s In the Hold (c.1913-14); Figure in the Landscape (1945) by Francis Bacon; John Latham’s Full Stop (1961), and Interior II (1964) by Richard Hamilton) play with the theme of abstraction and can be appreciated sensually in terms of their subject matter, use of shape, form, colour, and style. We speak to Tom Pursey, co-founder of Flying Object, about the impact of technological advances on visual art and the process of devising a multisensory interpretation of 20th century painting.

A: You have been awarded the IK Prize 2015. What does this accolade mean to you and how will exposure from the prize forward your work as a creative agency?

TP: It means a huge amount. We are still a young agency – we’ll turn two just after Tate Sensorium opens – and we are still finding out how we can best do the work that we want to do. The IK Prize has given us the opportunity to do two things that we, as an agency, are very keen on: to use technology to create immersive experiences that excite people, and to work with arts and cultural organisations in new and interesting ways. But more importantly, perhaps, it has afforded us a huge platform, as well as a chance to work with one of the world’s great museums and with a collection of first class artworks.

A: In your opinion, how important are awards such as the IK Prize for recognising the impact of digital technologies on art appreciation?

TP: I think the most important element of the IK Prize is how open it is. The brief was simply “connect the world with art”. There are so many ways that digital technology can augment the appreciation of art, and it’s crucial to be able to try out new technologies, and keep coming up with new ideas. Too often ‘digital’ means another app, or a game, or a website; something displayed on a screen. To break out of these all-to-familiar behaviours requires asking the right questions in the right way, having the budget and resource to support a good idea – and often, a fair bit of institutional bravery. The IK Prize provides a framework that allows all of this.

A: Flying Object has proposes a multisensory experience of a series of iconic works from the Tate collection. Can you describe the process of selection and collaboration between you and these pieces?

TP: Our first job was to build the team of wonderful people who specialise in different senses – hearing, smell, taste and touch. This included audio specialist Nick Ryan; master chocolatier Paul A Young; scent expert Odette Toilette; interactive theatre maker Annette Mees; lighting designer Cis O’Boyle; digital agency Make Us Proud; and the Sussex Computer Human Interaction Lab team led by Dr Marianna Obrist at the Department of Informatics, University of Sussex. Together we wandered the galleries of Tate Britain asking questions: what might this sound or feel like? Does this painting make you think about flavours or scents?

Doing that helped establish a role for the senses in the gallery space. That role is to encourage the visitor to develop their own responses to artworks, with the senses as stimulations, jumping off points. We realised the sensory stimuli could trigger thoughts or memories, focus attention on different parts of the artworks, and even bring out colour and aspects of shape and form. That was exciting, but it meant providing a sensory landscape that was open and varied, not single interpretations. We were very keen to avoid direct interpretation, and it’s made the result much stronger.

Early on, we decided to use only 20th century art. By moving away from direct representation we could lean into this open and fluid interpretative space. We wanted a broad range of pieces that can each be read in different ways. That’s more fun and interesting than – here is a bunch of flowers, and this is what the flowers smell like. After selecting our final four art works, each painting was assigned a lead sense, plus one or two others. We then formed small creative teams with the sense specialists to devise the individual experiences, responding to the painting and relevant information about its context or process of creation. We prototyped, tried things out, iterated, then staged a full dress rehearsal with friends – before iterating some more. It was a full creative process, during which the artworks seemed to bloom, offering more depth with every new approach.

A: The works included in Tate Sensorium are not obvious choices for adaptation. What challenges did you encounter when creating this project?

TP: Interesting you think that! As mentioned above, focusing on 20th century art and away from direct representation may not have been obvious, but on reflection has allowed us more space to work in. You might think you want a painting that depicts, say, something obvious to smell. But we realised we wanted paintings that had a broad range of interpretations. People respond to sensory stimuli differently – instinctively, and very personally. By choosing works without obvious readings we can use the senses to offer people ways to create personal connections unique to them.

The most difficult part was deciding what not to put in. Make it too complicated and no-one gets anything out of it. Each room has to work as a multi-sensory experience – the sight of the painting coupled with the two/three other senses we’re stimulating. A rather unforeseen challenge we encountered was around language. It’s quite hard to talk about, for example, smells, in a language that tends to be audiovisual – sounds to me like… the way I see it… and so on. When we’re talking about a scent that’s sharp, is everyone understanding the term in the same way?

A: How does Tate Sensorium correlate with the agency’s ongoing output?

TP: All our work at Flying Object is designed to engage people. We want to create things that people like, want to talk about, want to share with friends. That could be video designed for YouTube, or fun online interactive stuff, or real-world experiences like Tate Sensorium. In general we try to do a broad range of things – it’s challenging, in a good way, and having an approach that works across a range of areas keeps things interesting.

A: In what way do you see the technology developed by Flying Object being used in the future of art, and how does it seek to connect with wider audiences?

TP: I definitely think there is potential for elements of Tate Sensorium to re-appear in galleries and museums. We are at a point in technology where devices to create smells and haptic sensations are becoming more available. Meanwhile our understanding of how the brain processes sensory information has evolved massively in the last 10-15 years. You can see the impact of this in modern restaurants, and ideas that were initially the preserve of the Hestons of the world are now becoming more commonplace.

It is really important to us that we learn from Tate Sensorium – how do people react, how do the experiences impact how they view the art. We’re seeing it as an experiment and inviting people to take part, recording both biometric information as well as questionnaire responses, and sharing that information with the visitor. But it’s also important that we create something that people like the sound of, and an experience that’s fun and different. I think museums will reach a broader audience – specifically, a younger audience – by playing with the gallery space, and by cleverly bringing in technology, in a way that augments the experience but without distracting from the core focus.

IK Prize 2015: Tate Sensorium, 26 August – 20 September, Tate Britain, Millbank, London, SW1P 4RG.

Find out more www.tate.org.uk/sensorium.

Visit Flying Object’s website www.weareflyingobject.com.

Follow us on Twitter @AestheticaMag for the latest news in contemporary art and culture.

Credits

1. David Bomberg, In the Hold c.1913–4. Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1967. Copyright of Tate.