Thomas Heatherwick (b. 1970) is one of the UK’s most prolific designers. In 1994, he founded the eponymous studio with the mission to unite the disciplines of architecture, urban planning, product design and interiors into a single creative workspace. Since then, he’s been appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for services to the design industry and elected a Royal Academician. He’s worked on some of the most iconic projects of recent times: Azabudai Hills, in the centre of Tokyo; Google’s first purpose-built campuses in California; Little Island, a park and performance space on the Hudson River in New York; as well as the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town. Now, an all-new edition of Making, the definitive compendium of Heatherwick’s work, is published by Thames & Hudson. It’s an in-depth, behind-the-scenes look at the creative processes that drive the studio forward. It answers the question: “how did they do that?” with anecdotes and an unfiltered look at how he, and his team, turns ideas into reality.

A: Where did it all begin for you? What’s the story?

TH: I grew up in London and my early years were spent among people who pursued strong personal interests, exposing me to different influences and encouraging me to develop any natural aptitudes I might have. I spent time drawing, making and taking apart mechanical and electrical devices such as typewriters and cameras. I became curious about ideas, structures and problems being solved. After leaving school, I began a two-year diploma in general art and design, followed by an undergraduate degree in three-dimensional design at Manchester Polytechnic and then a two-year master’s degree at the Royal College of Art in London. In these seven years, my training allowed me to move freely between materials and processes: working with plastics, glassblowing, welding, jewellery-making, ceramics, embroidery and timber joinery. I was able to pursue my ongoing interest in the design of buildings and the built environment, and in 1994, I set up a studio to continue researching and experimenting with ideas and ways of making them happen.

A: The title of your book is summed up by one word: “making.” Does it mean something special to you?

TH: At this time, I became curious about the historical figure of the master builder, who had combined the roles and skills of the builder, craftsman, engineer and designer, which meant that the generation of ideas was connected to the process of turning them into reality. However, with the establishment of the Institute of Civil Engineers in 1818 and the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1834, engineering and architecture seemed to have evolved into elite professions with separate identities from the rest of the building trade. Now, not only was the designer of a building discouraged from having a creative connection to materials and practical making, but the craftsman lost his prestige, beginning the slow decline in skills and expertise within the building industry. My own experiences had convinced me that understanding materials, and gaining practical experience of using them, was essential to making ideas happen. For my degree course thesis, I interviewed architects, self-builders and contractors about their education and ways of working. At that time, young architects were given no practical experience of making, such as casting a form in concrete, making a timber joint or constructing a brick wall. Given that buildings are some of the largest objects made and experienced by humans, it was surprising that their designers were so far removed from the process of making. Later, studying at the Royal College of Art gave me space to think about the way in which I might practise when I left the education system. Instead of rigidly dividing artistic thinking into separate crafts and professions – sculpture, architecture, fashion, embroidery, metalwork and landscape, product and furniture design, I wanted to consider all design in three dimensions, not as multi-disciplinary design, but as a single discipline: three-dimensional design.

A: There are 150 entries in this volume. Looking back, is there an early project that is particularly meaningful?

TH: Whilst I was studying, I developed a particular way of thinking through making. Instead of starting with a drawing or a discussion, I used test pieces in the workshop to find ideas. Amongst the earliest included in the book are from 1990. I was trying to avoid needing an outcome and, instead, adopted a spirit of purposeful aimlessness. For me, most of these experiments were mini-mission statements for architectural projects. I wondered how each one might translate to the scale of a building or piece of furniture, or how a twist, joint or texture could become an element like a roofing membrane or cladding system.

A: How has this approach translated to today? Can you tell us about the most recent project in the book?

TH: For Space Garden (2023), we’ve been working with Ekblaw’s Aurelia Institute to imagine 36 controlled growing environments to house different plant species, to be sent into orbit for a 12-month research experiment. The project is currently in development, with the intention that, in the nottoo-distant future, it will be a beautiful landmark in low Earth orbit. We imagine it as an inspiring vantage point from which to look back at Earth and appreciate it as our only home in the universe, and somewhere we must protect at all costs.

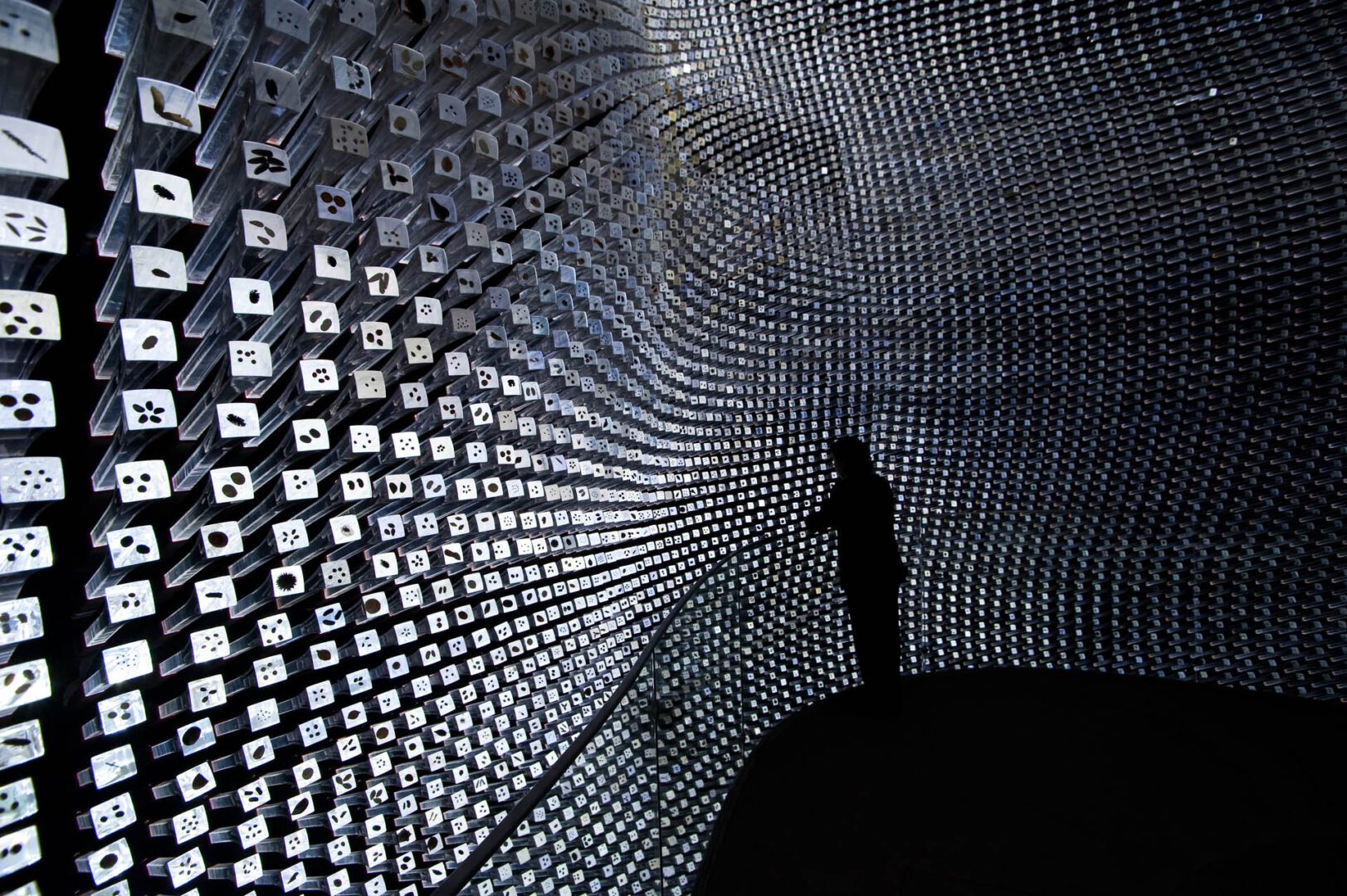

A: The UK Pavilion (2007), which is otherwise known as The Seed Cathedral, is one of your most visually recognisable structures. How did it come into being?

TH: In 1851, the first world’s fair was held in Hyde Park in London. It’s now called World Expo. Nations of the world create government-sponsored pavilions that promote their country, economy, technology and culture. We won the competition to design the pavilion that would represent the United Kingdom at the 2010 World Expo, held in Shanghai, China. It was the largest ever. We imagined governments of every country saying the same things to their designers: “Show that our country has a strong economy… Show our splendid industry… Show that we are a good country for a holiday… Show our cultural diversity… Show that we are sustainable.” But in the final paragraph, the UK’s brief changed tone: “When people vote for the best pavilion, make sure that you are in the top five!” Every pavilion was an advertisement for its country. What could we say about the UK, and how? Research showed that the perception of the country in much of the world still carried lingering stereotypes of London smog, bowler hats, Marmite, double-decker buses, the Royal Family and red telephone boxes. How could we get away from these clichéd, old-fashioned stereotypes and better reflect the inventiveness and creativity of contemporary Britain?

A: What was the outcome? How did you find a solution?

TH: With its slogan “Better City, Better Life”, the theme of the Expo was the future of cities. We decided to consider the relationship of cities to nature. Since 2000, Kew Gardens has been running the Millennium Seed Bank, which aims to collect and preserve 25 per cent of the world’s wild plant species. A critical moment in the early stages was when its Director agreed to provide us with 250,000 seeds. The result: 60,000 silvery, tingling hairs protruded from every surface, making a structure six storeys in height. Inside, their tips – into which a quarter of a million seeds were cast – formed a curvaceous undulating surface. Two weeks before the end of the Expo, it was officially announced that the UK Pavilion had won the event’s top prize, the gold medal for Pavilion Design.

A: In recent years, the studio has been involved in shaping cities and towns. What’s that been like?

TH: The greatest need for innovation seems to be in finding ways to apply artistic thinking to the problems of a city, rather than automatically emulating Bilbao, where an extraordinary art gallery transformed its fortunes. For example, in designing a new bio-mass power station in Middlesbrough, there was an opportunity for the area to develop a new identity by investing in necessary renewable energy infrastructure, which would at the same time be a park, cultural facility and educational resource. On our huge new district projects, London Olympia, Xi’an CCBD in China, and Azabudai Hills in Tokyo, we have been investigating what new kinds of public space can offer the occupants of a crowded city. It’s about how to use materials and forms at a human scale, at which people touch, experience and live in the world.

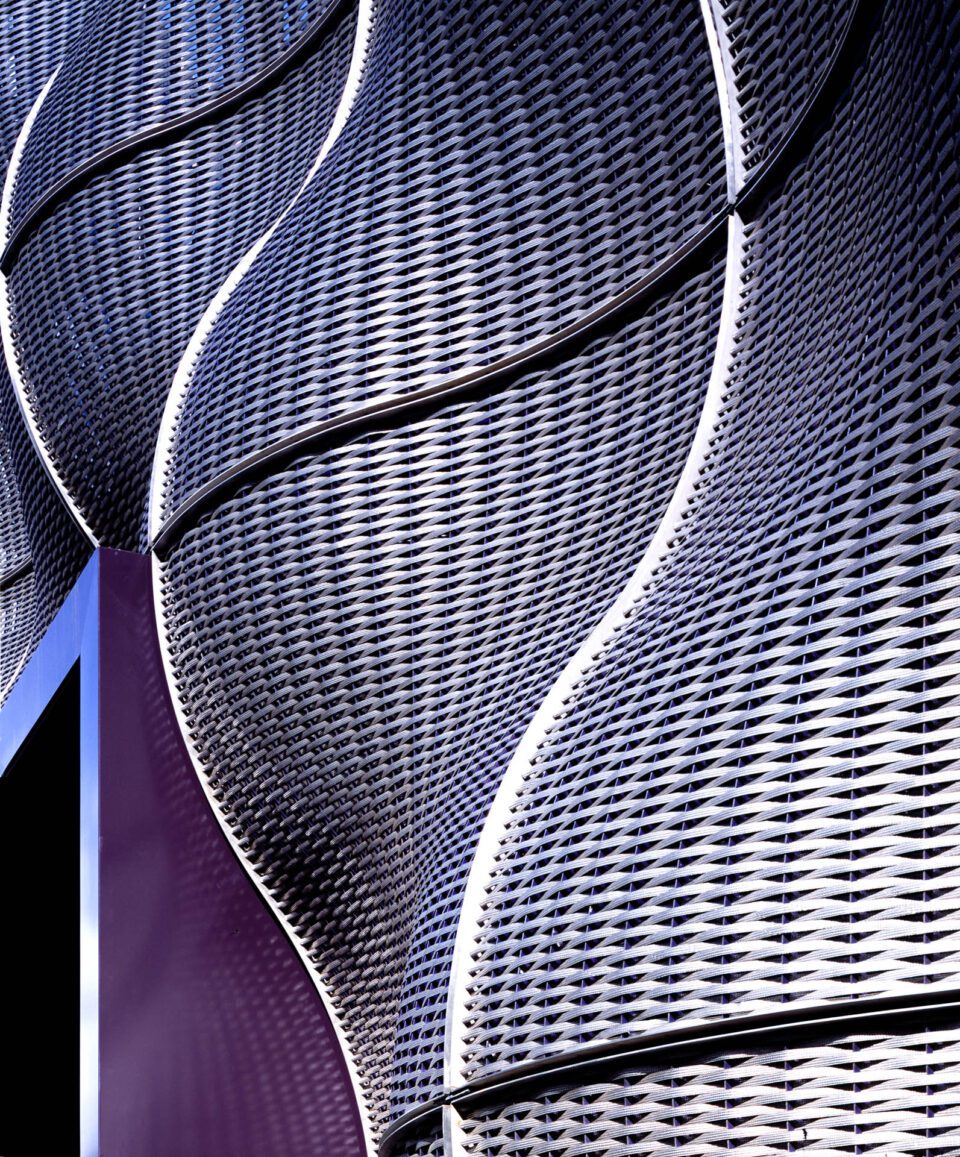

A: It’s quite a big shift – from pavilions to whole districts. Can you tell us about a difficulty you’ve faced?

TH: The process of getting planning permission for Coal Drops Yard was not smooth. Historic England liked our design, but the city planner was not convinced. He commented that we were not sufficiently respecting the sense of the warehouses as a pair. We went away dejected, sure that we were right, and frustrated that he was not understanding us. But we decided to take his feedback on board and play with the roof. Surprise, surprise, the project got stronger and more interesting. I was proud of my team for not always thinking we were right and embracing the challenge we had been given. I am grateful to the planner pushing us to make something better. His job was to represent the public – we are passionate about the public too. We both wanted the same thing. I love this story: he was right, and we learned from him.

A: Every project is introduced with a question: “Can a building help you heal? Can a strong structure look delicate?” What role does this play in your process?

TH: We have found that we tend to guide ourselves towards ideas by finding a few key questions to ask ourselves. These descriptions may give the impression that ideas come easily, but almost every project, whether it is built or not, is an intense mixture of certainty and doubt, breakthroughs and dead ends, tension and hilarity, frustration and progress.

Thomas Heatherwick: Making | Thames & Hudson

Published 16 January

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image credits:

1. UK Pavilion, (2007). Image: Daniele Mattioli. © Heatherwick Studio

2. Coal Drops Yard, (2013). Image: Luke Hayes. © Heatherwick Studio

3. Guy’s Hospital, (2004). Image: Edmund Sumner. © Heatherwick Studio

4. Google Workspaces, (2014). Image: Christopher McAnneny. © Heatherwick Studio

5. Guy’s Hospital, (2004). Image: Edmund Sumner. © Heatherwick Studio