Aïda Muluneh. Mous Lamrabat. Prince Gyasi. Thandiwe Muriu. Zanele Muholi. These are just a few contemporary African photographers – from Ethiopia and Ghana to Kenya and Morocco – making waves in the art world. But, what about those who came before? Archivist and writer Amy Sall addresses this question in her new book, The African Gaze. Published by Thames & Hudson, this stunning compendium takes the reader on a journey through time to uncover Africa’s greatest lens-based practitioners. There are 25 photographers and 25 filmmakers featured, each with biographies that place them in context and footnotes that invite readers to learn even more. Some of the artists included are already starting to receive more international recognition, such as Seydou Keïta, Sanlé Sory and Ernst Cole. However, the volume really shines when it comes to spotlighting past visionaries overlooked by the canon.

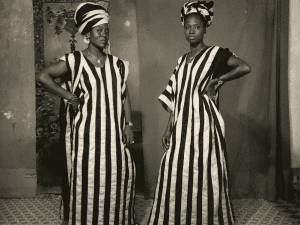

Many will know Keïta’s studio photographs showing the fashionably dressed people of Mali. However, fewer will recognise the name of his mentor, Mountaga Dembélé (1919-2004), who dubbed himself the “first Black photographer in Bamako.” Sall introduces us to him in The African Gaze, highlighting the artist’s archive of family portraits. One shows two women with arms over each other’s shoulders and fingers interlaced. Dembélé overlays purple and gold over the monochromatic base photograph to inject colour into the accessories and clothes of his subjects. The lens-based artist was known for his powerful vision for the overall piece and would often direct the poses of his clients in order to achieve the most interesting final result. In an interview with scholar Érika Nimis, Dembélé shared: “I decided on the poses people took… I organised all of that myself…Even the way the bandanas were tied, I did it for them.” As the Malian photography scene grows bigger and bigger – with events like Bamako Encounters spotlighting lens-based creativity since 1994 – this is a moment to give credit to an early pioneer of the medium.

We are also introduced to the late Felicia Abban (1935-2024) – who is considered the first woman photographer in Ghana. She was able to build an impressive 60 year career for herself in a male-dominated field, which is reflected through the fact that she is one of very few women in Sall’s book. At age 18, Abban set up her own photography shop called ‘Mrs Felicia Abban’s Day and Night Quality Art Studio’ and gained renown through the years to the extent that, in the 1960s, she was the photographer of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972). Today, she is famous for her self-portraits, which she used to advertise her business, build her skills and as a mode of self-expression. In one shot, she wears a bright smile along with an ornately patterned dress, white gloves and flower-adorned cloche hat. In 2019, curator Nana Ofosuaa Oforiatta Ayim selected Abban’s work to be part of Ghana’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Ayim, who got to know Abban in the last years of her life, stated in an interview for Document that: “in her own words, she said she thought she could portray women better than the men around her.”

As Sall aptly states in her preface: “expression through the camera underscored a necessity, desire and right to portray African people as they were and as they wished to be seen.” In recent years, we have seen the art world begin to recognise African photographers with exhibitions like A World in Common at Tate and 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair. This delayed recognition does not mean that photographers from the continent are only emerging now. Forebears such as Dembélé and Abban have long been using the camera as a tool for expression. The African Gaze spotlights those overlooked by history. It’s an essential archive that enriches our knowledge of past pioneers and preserves their names for generations to come. Packed with reference material, Sall’s book is an entry point into the breadth and beauty of African photography.

The African Gaze | Thames & Hudson

Words: Diana Bestwish Tetteh

Image Credits:

- Je vais décoller, (1977). © Sanlé Sory, Courtesy David Hill Gallery, London.

- Untitled, Podor, (1963-78). © Estate of Oumar Ly.

- Filles du bar-dansing, Léopoldville, (1955-65). © Jean Depara, Courtesy Revue Noire.

- Self-portrait, from 70’s Lifestyle series, (1975-78). © Samuel Fosso, Courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris.