A new publication foregrounds an age of innovation and experimentation, pushing the boundaries of architecture through poetic and geometric forms.

Villa Além (2014) stands in a cork forest in Portugal’s Alentejo region. It’s a striking and compelling house – nestled in a rugged, rural setting – not least because of its unique and unexpected appearance, but also its thick, angular concrete. It boasts flaps that splay skyward like an opened cardboard box. It was self-designed as a home for the Swiss architect Valerio Olgiati (b. 1958). Minimal and geometric, it is one of the most staggeringly beautiful examples included in Concrete Houses, a new publication by Melbourne-based writer Joe Rollo. The 312-page tome is released by Thames & Hudson Australia, and is an ode to concrete – to which Rollo has dedicated his entire career. He has been the Editor of C+A Magazine for the last 15 years – a biannual publication promoting the breadth of possibilities offered by the material. Though this work has stretched into the better part of two decades, his passion is unwavering: “Concrete offers an unlimited exploration of structure and shape. It has conviction, strength and directness, but plasticity, too, which makes the possibilities for form-making almost endless.”

In its earliest usage, concrete can be traced back to the pyramids of Egypt, but the Romans were the first to take it to full effect – moulding impressive decorative structures like the dome of the Pantheon. Concrete’s use has ebbed and flowed since, being overlooked for a period before widespread use by Modernist architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Oscar Niemeyer and Walter Gropius – who experimented when building the Bauhaus school in Dessau.

Poetic, hard-wearing, heavy, malleable, concrete’s mix of water, aggregate and cement is fluid enough to explore sharp angles and sinuous curves of any given mould, before setting into its permanent state. Concrete’s surface is created in any number of ways – from the board-marked textures of Modernism to the bush-hammered language of Brutalism, as well as the trend for tinted and polished finishes today. It’s a material that has consistently sparked curiosity in designers, pushing the boundaries of form work and inventing new possibilities for fluid constructions.

Rollo explains: “You can achieve a multitude of shapes that you would not otherwise achieve easily.” In this way, he views the featured buildings as a source of idea generation for both architects and clients about what happens when you really push the limits. Advances in technology have expanded this further. “Computers and CAD drawings enabled designers like Zaha Hadid to manifest extremely complex shapes,” he says, referring to the characteristically swooping shapes deployed by the late Iraqi architect and innovator.

Rollo presents a snapshot of what concrete can be – beyond the material’s history. He offers a collection of 19 houses constructed between 2007 and 2018. They have all been plucked from the pages of C+A, a kind of “best list” of projects that have landed on his desk over the last decade. They take us on a journey from Australia to Japan, Sweden to the USA, and through world-class practitioners including Sou Fujimoto, Marcio Kogan and Tom Kundig.

With Villa Além, Rollo explains how the traditional walled garden has been reinterpreted and given a “monumental character.” A red tinge has been added to the mix – a concession to the house’s context, helping the walls harmonise with russet soil. The building is connected with the colour and texture of the earth, as if planted there. Walls reaching up to 5.5 metres fold over as flaps that provide necessary shading. The architect, Valerio Olgiati, described these elements as “petals.” They’re fundamental to the play between light and shadow that keeps a succession of austere and practical rooms cool. “Thermally, concrete is an incredibly well-suited material for heat retention and for cooling – in countries like Australia, Spain, Brazil and Portugal.”

Another structure that is deeply integrated into forestry is Hiroi Ariyama and Megumi Matsubara’s It is a Garden (2016), in Japan’s Nagano Prefecture. The building casts assumptions aside that concrete is conducive with hermetic spaces. Conceived as a guest house, It is a Garden includes a series of five courtyards to let the woodland break through and open up the building into the sky. Huge panes of glass, clean lines act as a framework, which ensure the canopy is always visible – always to be recognised. “From just about anywhere you get glimpses of the woodland,” says Rollo, “whether you’re looking up or inwards.”

Whilst concrete is used as a framing device in Villa Além and It is a Garden, the smooth walls of Tom Kundig’s The Pierre (2011) are masterfully spliced with a craggy rock on Lopez Island, Washington, facing the sea. Set on the shoreline, the chunky residence seems purposefully wedged in stone, as if the weather might otherwise carry it away. The American architect is famed for joyful contraptions – pulleys, levers and rollers – but the playfulness in this project comes from the pairing of natural and manmade elements. A tiny cave-like bathroom is carved into the rock and the waste is used as aggregate for the terrazzo flooring in the living space, where an outcrop of stone is met by smooth, vertical concrete wall to form a hearth. It’s a clever intervention impossible to imagine with any other material.

If The Pierre seeks to make a statement, Dovecote (2016) by Azo Sequeira Arquitectos Associados is about subtly preserving a historic way of life. The house, situated in Braga, Portugal, is in fact a playroom that replaces a derelict dovecote in the garden. Poured within a wooden mould, the walls are veined with the faint impression of the grain. A small triangular opening, cut into the apex, is a nod to the doves that once flew through such an opening to roost.

These understated details show how delicately concrete can be employed, poured and, eventually, decorated. “It became an exercise in replacing the previous form.” says Rollo. The showstopper is the small gap at the base of the house, which creates an illusion of levitation – enabling light to seep through. “From some angles it looks like it’s floating,” says Rollo. Azo Sequeira adds: “We wanted the room to be inspired by magic, fantasy and also by childhood dreams. We decided to transform the old blueprints into a minimal tree house that represented memories and imagination of purity of light and peace.”

An architecture publication penned by an Australian writer would not be complete without the inclusion of Peter Stutchbury. Invisible House (2012) is sheltered by the Blue Mountains under a vast cantilevering roof. It acts as an awning to shelter a terrace bound by walls compiled from cuts of mesmerising pink sandstone and supports a suite of rusted steel boxes that act as periscopes. Whilst considered a relatively low-cost material in the UK and the USA, the intensive labour involved in producing a concrete building makes it a luxurious choice. “As much as I’d love to have a house like this, I couldn’t afford one,” Rollo states wryly.

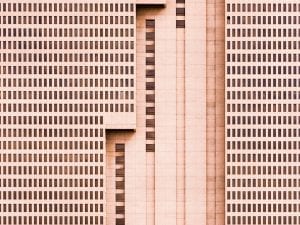

In an inner-city context, set amidst Edwardian-era dwellings in Melbourne, Andrés Casillas De Alba and Evolva Architects’ Camberwell House (2015) draws inspiration from Pritzker Prize-winning architects Luis Barragán – known for brightly coloured, geometric forms – and Tadao Ando – acclaimed for using raw grey concrete. The pock-marked rectilinear walls and a pop of lurid pink paintwork pays homage to them both. “Camberwell House was designed by an architect who had worked with Barragán. However, it actually fits in with the streetscape – the house has that warmth that you wouldn’t normally expect of a modern building.”

For the home of an art collector in Sydney, Indigo Slam (2016), Smart Design Studio created an experimental design that brings together expressed barrel vaults, tilted skylights and smooth curves in a single sweep – rightly described by Rollo as taking on the appearance of a pop-up book. “Concrete has gone from a purely utilitarian material for industrial applications to being used in much more creative ways,” he says. At first glance the heavy use of the material does not appear conducive to the environment, but the angles and openings help to channel in natural light and aid cross-ventilation. Geothermal heating and cooling are also present, as well as solar panels and rainwater harvesting. Inside, the spaces are bright and tactile, the curves softened by white paint and a palette of stone, brick and wood. “Internally it need not be a cold material to live with,” says Rollo.

Whilst the climate crisis has sharply highlighted concrete’s negative traits – if it were a country it would be the world’s third largest carbon emitter after China and the USA – environmental damage has also brought an impetus for innovation across all fields of study and construction. The plasticity of fibreglass is a starting point. Fibre concrete negates the need for steel reinforcing rods and has been used by the likes of Zaha Hadid Architects in projects such as the Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku (not included in the text). “Technology and the new developments of CAD designs mean that we can create shapes that would have been so laborious and time-consuming that the costs would have been prohibitive,” says Rollo. The continually developing world of 3D printing has also brought an economic use of resources with its ability to create structures without form work, whilst researchers at ETH Zurich have also done away with ridged moulds to come up with a digital fabrication technique using woven yarn known as KnitCrete, which ensures that building in concrete will become more sustainable in years to come.

Across Europe in particular, concrete has long been associated with an intensive period of postwar construction. Many of these public buildings and housing estates now face demolition or remodelling, such as the Birmingham Central Library which was ripped down in 2013. Opinion of the Brutalist style has swung from positive to negative and back again, especially as so few examples of the movement remain intact. The Bauhaus centenary has changed many perspectives once again, asking questions about beauty and function through open interiors, minimal aesthetics and a lack of ornament in an age of over-distraction. Rollo’s collection, with its sweeping curves, block-minimal lines, monumental towers and mesmerising spaces, does the same. It offers architecture as a poetry of geometry and mathematics – blueprints pushed to the limits of gravity and perception.

Jessica Mairs

Concrete Houses is published by Thames & Hudson.

Dovecote Braga, Portugal, 2016. Architect: AZO SEQUEIRA ARQUITECTOS ASSOCIADOS. Image: Nelson Garrido.

Lune de Sang Pavilion, Northern New South Wales, Australia, 2018. Architect: CHROFI. Image: Brett Boardman.

Camberwell House, Melbourne, Australia, 2015. Architect: ANDRÉS CASILLAS DE ALBA AND EVOLVA ARCHITECTS. Image: John Gollings and Jeremy Weihrauch.

It is a Garden, Nagano, Japan, 2016. Architect: ASSISTANT. Image: Daici Ano.

It is a Garden, Nagano, Japan, 2016.

Architect: ASSISTANT. Image: Daici Ano.