In a complex world, approaches to the time-honoured theme of representation are shifting. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, celebrates a diverse range of methodologies through the latest edition of the longstanding New Photography exhibition. The show’s curator, Lucy Gallun, discusses the history of the initiative and the unique qualities of this year’s iteration, Being.

A: The exhibition comprises work made since 2016. Why is it important to highlight such recent images?

LG: Many of the works in the exhibition are made quite recently — from 2016, 2017 and even some from 2018. With the New Photography exhibitions, the Museum has an opportunity to reflect upon some of the most urgent issues that artists are grappling with whilst presenting recent work to our audiences. The particular theme of this exhibition, “Being”, came simply from looking at a lot of new work and wanting to react to the expansive ways in which artists are confronting representations of their own lives and the lives of others. I also immediately noticed that this complex theme might feel different in tone from that of the last iteration of — Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015, of which I was also one of the curators — and I was eager to emphasize the range of different paths that could be explored in the exhibitions from year to year. I’m sure the exhibitions to follow will continue to explore a wide variety of themes.

A: New Photography foregrounds both emerging and established practitioners. How does the initiative impact the careers of chosen artists?

LG: Some of the artists included in the exhibition are just starting out in their careers (for some, this will be their first time exhibiting their work at an institution in New York), whereas others have more established practices and have, in some cases, been supporting the field of photography through teaching or other means. But for all the artists, this will be the first exhibition of their work at The Museum of Modern Art. New Photography has long been an important part of the contemporary program at MoMA, providing an opportunity to present new work by a diverse array of artists. Indeed, even from the first exhibition in 1985, the photographers included were of different ages and were not all at the same stages of their careers. The exhibition continues the museum’s long tradition of commitment to the work of less familiar photographers of exceptional talent.

A: The theme for 2018’s show is human experience and personhood. How have the selected practitioners succeeded in responding to this universal theme in unique ways?

LG: All the works in the exhibition take on charged and layered notions of personhood and subjectivity using photography or photo-based media. Some works might be considered figurative in a more straightforward sense, while others do not include depictions of the human body at all, but despite such differences in approach, all the works in the exhibition contend with representations of people. In this way, the exhibition is organized around something that we all share – humanity – but also inherent in these artists’ representations is the recognition of difference: they respond to a diversity of lived experiences and circumstances.

A: Rights of representation are contested for many individuals in contemporary society. How do these artists disrupt traditional notions of photographic composition?

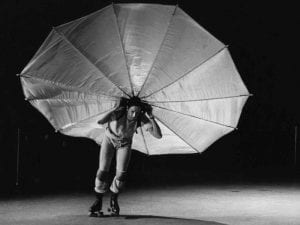

LG: Many of the works included in the exhibition do deploy conventions of lighting and pose that have been traditionally associated with studio photographic portraits, but interrupt these mechanisms in various ways. For example, some utilize recently-ubiquitous photo-technologies, such as facial recognition software associated with smartphone cameras. In other pictures, bodies or parts of bodies (appendages, faces) are multiplied, causing slippage between them and confusing our understanding of where one being begins and another ends. Some artists have removed recognizable physical bodies altogether, leaving only the debris left behind from the studio session or the traces of a physical presence. Or in other pictures, a model or a sitter may be physically present, but their face has been covered or obscured. At a time when representation is contested or fraught for many (for many people, a photographic likeness can present a political or emotional threat, for example), these artists consider the operations and parameters of standard photographic portraiture even as they disrupt them.

A: How does this edition of New Photography stand out or differ from previous iterations?

LG: The first New Photography exhibition was organized by John Szarkowski in 1985, and from the beginning the exhibition series had a goal of presenting work that, in his words, “seemed to represent the most interesting achievements of new photography.” From then onward the exhibitions were held yearly, and the format of the exhibitions usually consisted of separate, individual presentations of works by three to six artists, without connections being drawn between the different artists’ bodies of work. Starting with the last exhibition, which took place on the 30th anniversary of the beginning of the series, we’ve updated the format. We are now presenting thematic exhibitions that are held less frequently, though still at regular intervals (around every two years), and they are much expanded in terms of their size, which allows us to examine themes across the field of photography and to draw connecting threads across the artists’ practices.

A: What does MoMA have on the horizon for the rest of 2018?

LG: In the short term, I am currently organizing another upcoming photography exhibition, Projects 108: Gauri Gill, opening at MoMA PS1!

The exhibition runs from 18 March. Find out more here.

Credits:

1. Sam Contis. Denim Dress. 2014. Pigmented inkjet print, 31 5/8 × 41 11/16″ (80.3 × 105.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Thomas and Susan Dunn © 2018 Sam Contis