CasildART, located in the heart of Connaught Village, London, showcases the very best in contemporary Black art. The gallery spotlights works from emergent and mid-career artists from the UK and African diaspora, highlighting the breadth and diversity of Black creative expression. Their latest show is In His Own Image, presented as part of Connaught Village Art Month, which considers how Black male bodies have been projected upon, festishied and distorted by dominant cultural narratives. Twelve artists, including Richard Mensah, Sol Golden Sato, Matthre Small and Richard Mensah, engage in the radical act of self-definition, constructing, challenging and reimagining their identities. Aesthetica spoke to the show’s curator, Sukai Eccelston, about how In His Own Image invites audiences to witness the fullness of Black male experience and contribute to broader conversations about what it means to see – and to be seen.

A: Take us back to the start. What was the initial spark of inspiration behind In His Own Image?

SE: First of all, CasildART serves as a platform for artists of African and Caribbean heritage. Our gallery is dedicated to creating, showcasing, preserving heritage, and amplifying Black narratives. In His Own Image was a response to the widespread conversations about masculinity in the media and workplace. These discussions tend to be quite binary, usually focusing on white men and women, which often leaves Black men excluded from these broader conversations about masculinity. At the time these conversations were going on, I was reading bell hooks’ About Love, in which she explores how Black masculinity has been shaped by white patriarchal capitalism – a system that doesn’t serve Black men, and often creates challenges in how they see themselves and relate to others. One line in particular stayed with me: “If men are to liberate their souls, they must be willing to confront the ways they have been taught to think about masculinity.” On a personal level, I have two sons, and I don’t want them to be confined or limited by the stereotypes society places on them. I’m very aware that we all hold multiple, fluid identities, but Black men often have to adapt in subtle, sometimes invisible ways. In His Own Image grew out of that tension: a desire to explore and reframe what it means to exist, love, and thrive as a Black man today.

A: Tell us about the curation of the show. How did you narrow it down to these thirteen artists?

SE: For me, curation is storytelling. I wanted to tell a more complex story about masculinity. The process is also a bit like matchmaking – I looked for conversations between artists, for works that spoke to different dimensions of Black masculinity, from the deeply personal to the societal and political. In His Own Image brings together 13 contemporary male artists working mainly in painting but we also have some mixed media pieces in the show. It foregrounds themes of identity, vulnerability, intimacy and self-representation, creating a dialogue between the art, audience and wider community.

A: What role does art play in challenging dominant cultural narratives and fostering self-definition?

SE: Art is a mirror, a megaphone and sometimes a hammer – all at once. It can comfort, but it can also confront, and both are necessary. Transformation often begins with being uncomfortable. Art allows people to connect to a story in subtle and nuanced ways. It gives artists a way to speak their truth – to express what matters to them and to make sense of their world. For many, it’s the only place they can speak from authentically. When a work of art doesn’t come from that place of truth, it can feel hollow or soulless. Even when it carries contradictions or conflicting messages, it still reflects who the artist is – and that’s what gives it power. It is also about preserving legacy and heritage, ensuring that our stories, identities and experiences are not lost or defined by others. Importantly, artists don’t tell you what to think and there isn’t one single truth or one way of being a Black man. Each story is valid because it emerges from the artist’s own background and experiences – the things that have shaped their identity.

A: Family and community are central to many of the works on display. How do these relationships shape Black male identities – both nurturing and constraining them?

SE: Family and community are strong themes in the exhibition. Works like Wesley George’s Saturday Afternoon and Gabriel Choto’s Emotional Odyssey explore the expectations, pressures and joys of family life. Sometimes those expectations can feel like a heavy burden, but they also create space for cultural and creative expression. These relationships shape identity in complex ways: they ground us, but they also push us to define ourselves. The works capture that push-and-pull and, I hope, will resonate with audiences.

A: How did you balance the intimate and political when putting together the show?

SE: We did this by treating intimacy as political, and politics as intimate. For Black men, as for everyone, personal experiences are deeply shaped by the world around them. The two can’t really be separated. Take, for example, Richard Mensah’s Subterranea and Dance of a King – the latter a tribute to Fela Kuti, the creator of Afrobeat. At first glance, it’s a portrait of a man dancing to music, lost in his own groove. But it’s also profoundly political. Fela used music and performance as acts of resistance, yet he was equally celebrated for his style, sensuality and sartorial confidence. That blend of expression and defiance (to be seen) captures the heart of what this exhibition is about. Similarly, Wesley George’s Lovers Rock is an intimate portrait of a young couple sharing, perhaps, their first dance. These quiet, personal moments carry as much power as overtly political works. The key is to honour the experience while acknowledging broader social forces, without turning the gallery into a sociology classroom.

A: The exhibition is part of Connaught Village Art Month. What opportunities does this event offer that feel different from more traditional gallery exhibitions or art fairs?

SE: CasildART is a social enterprise, not a commercial gallery: we sit at the intersection of art, culture and community. We act as a hub for artistic and intellectual exchange, offering exhibitions and educational programmes that support artists and engage communities. This work is vital in diversifying the art world and ensuring that the contributions of Black artists are recognised and celebrated. The experience we offer is different. We’re not just showcasing art; we want the work to move people, to start conversations, and to create genuine connections. For us, it’s about engagement as much as raising awareness and visibility of contemporary Black art.

A: The featured artists are from all around the world, such as Sol Golden Sato, who grew up in Malawi before moving to the UK. How did you navigate the intersection of national and cultural identities?

SE: This really comes through in the work itself. Identity is layered – national, cultural, personal – and in this show, we let those layers speak for themselves rather than flattening them into a single narrative. Sol Golden Sato has three works in the exhibition. His painting Dionysius SuperFreaks explores eroticism as a cultural and political force within Black British life. Inspired by the underground blues parties of 1990s Brixton, spaces of joy, resistance, and community for Black migrants excluded from mainstream nightlife, it channels that energy into an ecstatic, sensorial composition. We also have works by Ethiopian artists Tsehay Nigatu and Natnael Ashebir, who both explore the body as a vessel for introspection, vulnerability and resilience. Ashebir’s Story of the Wind series merges history, memory and belonging, creating spaces where past and present converge. Each artist tells his story from a unique cultural vantage point, but together, they form a cohesive narrative.

A: Artists like Matthew Small paints on reclaimed objects such as car bonnets and signage. How do these material choices reflect the way identity is constructed and perceived?

SE: The materials an artist chooses are deeply connected to their practice. They form the foundation of creative expression and often carry symbolic meaning. Materials might be selected for their aesthetic qualities or functional purpose – even to challenge our idea of ‘fine art’. Matthew Small’s choice to work with scrap metal and found wood is both deliberate and poetic. By painting portraits of young men and boys on reclaimed materials, he transforms what has been discarded into something beautiful and worthy of our attention. The surfaces themselves weathered, chipped and imperfect are layered with meaning, mirroring the complex narratives surrounding identity, value and visibility. His portraits are soulful and powerful, drawing you directly into the eyes of his subjects. In doing so, Small compels us to see and value young Black boys (and girls) – too often overlooked, stereotyped or discarded. Through his work, the materials and the subjects become inseparable: both are reclaimed, reimagined and given new dignity.

A: How do you see the role of exhibitions like this in reshaping institutional narratives about race, gender, and power?

SE: Exhibitions like In His Own Image are small revolutions within the art world. They challenge dominant narratives, broaden perspectives and create space for voices that have long been marginalised. CasildART serves as both a convenor and an incubator, a place where new stories can take shape and emerging talent can find a home. For many artists, our gallery is the first space where their work is exhibited, and that early opportunity can be truly transformative, not just for their practice, but for how they see themselves within the wider art ecosystem. In the last five years, some institutions have showcased Black artists, but there’s still a long way to go. Too often, museums present a “whitewashed” version of history and culture that reinforces old hierarchies. Institutions have a responsibility to continually re-examine their practices and embrace multiple perspectives. But real change will only happen when the teams behind the scenes – from curators to senior leadership – are as diverse as the communities they claim to represent.

A: How do you hope audiences engage with the show?

SE: I hope audiences pause, look closely, and really see the humanity in each artist. I hope they laugh, reflect and maybe even disagree – that’s part of honest engagement. And maybe they’ll find an emotional connection with one or two pieces that lingers long after they’ve left the gallery. Mostly, I want people to leave with a renewed sense that we are all complex, evolving, and – if we allow ourselves – deeply human.

Scene VII: In His Own Image is at CasildArt until 8 November 2025: casildart.com

Words: Emma Jacob & Sukai Eccleston

Image Credits:

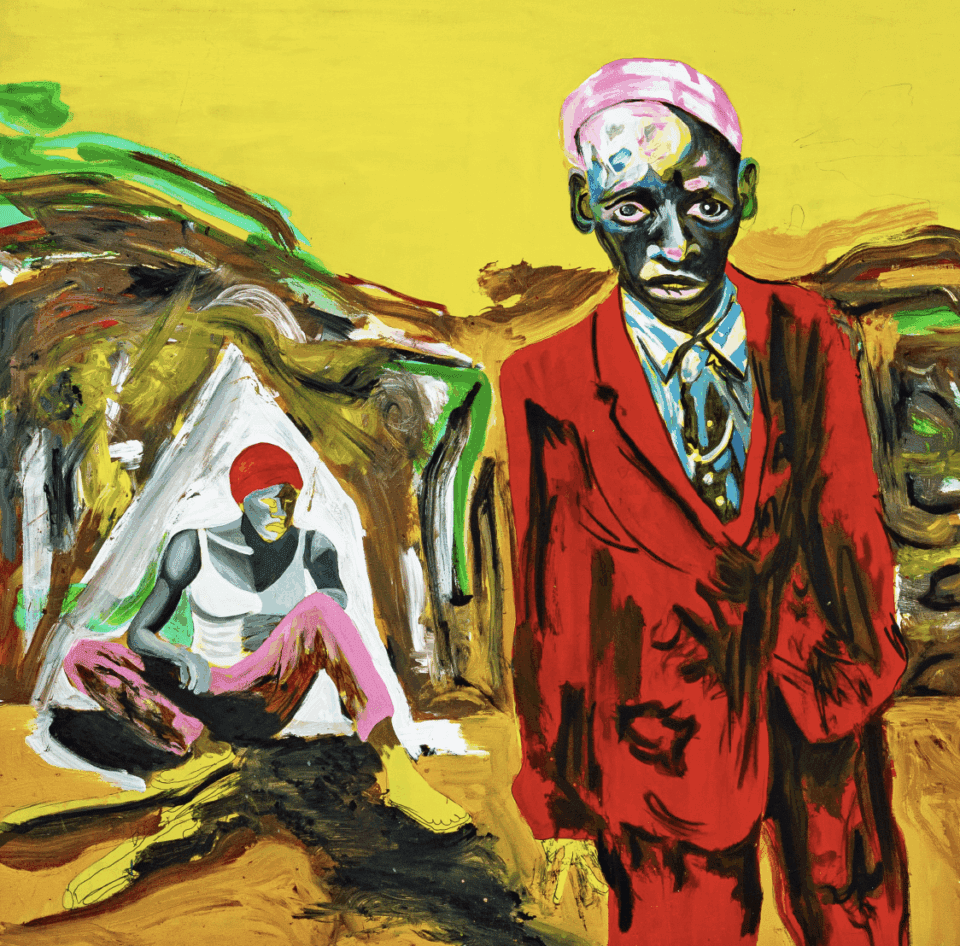

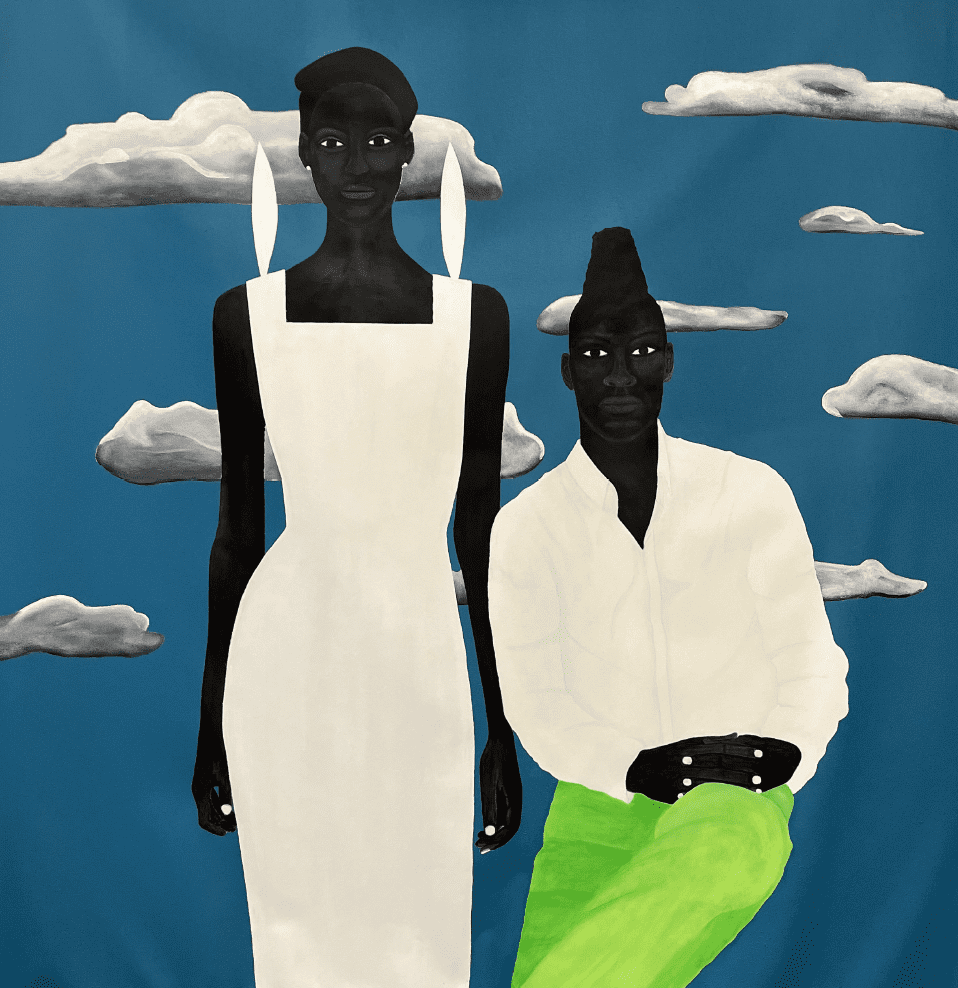

1&5. Christian Hiadzi, BECOMING II, Acrylic on canvas, 120 x 115 cm.

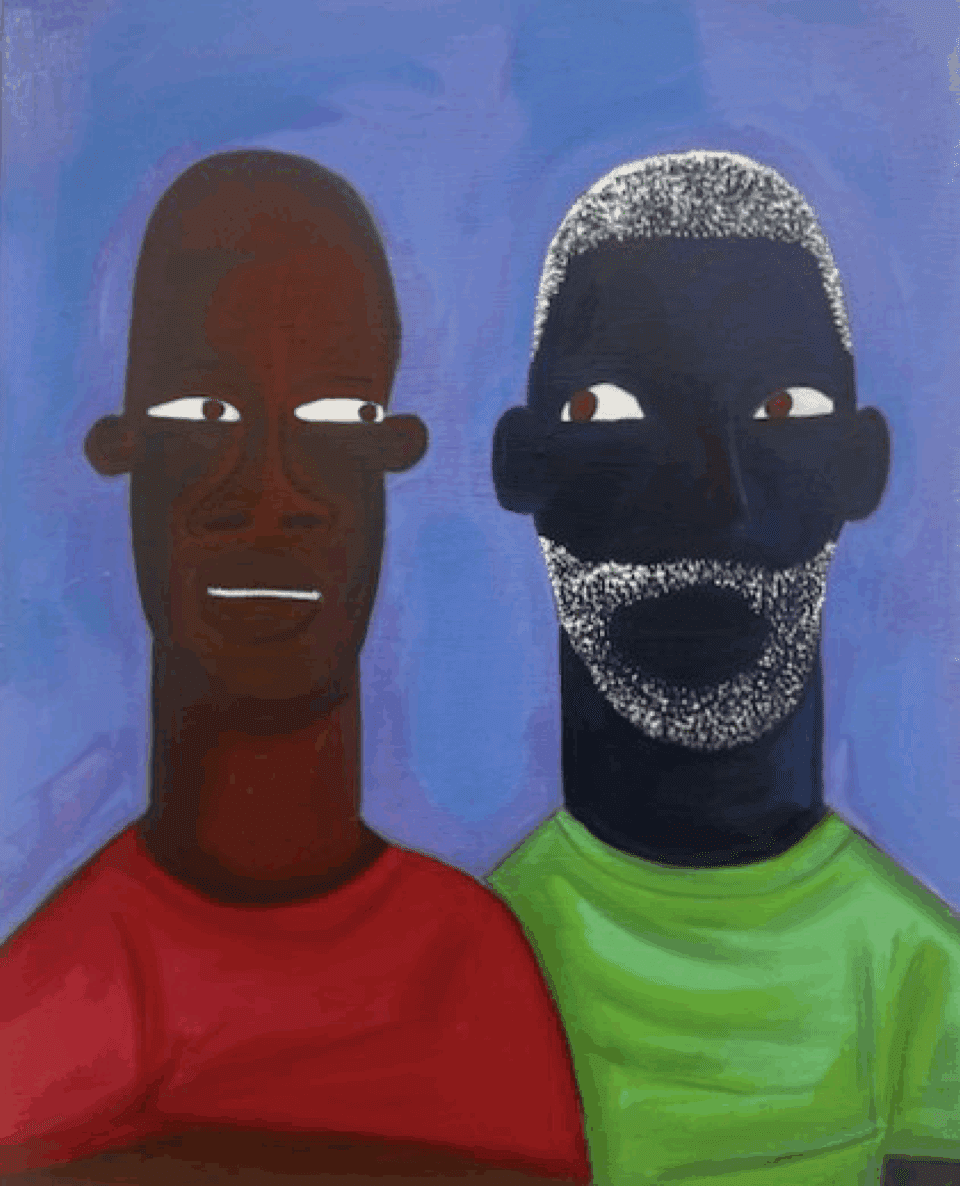

2. Sol Golden Sato, MR RARE EARTH’S TYCOON, 180 x 180cm, displayed at CasildART.

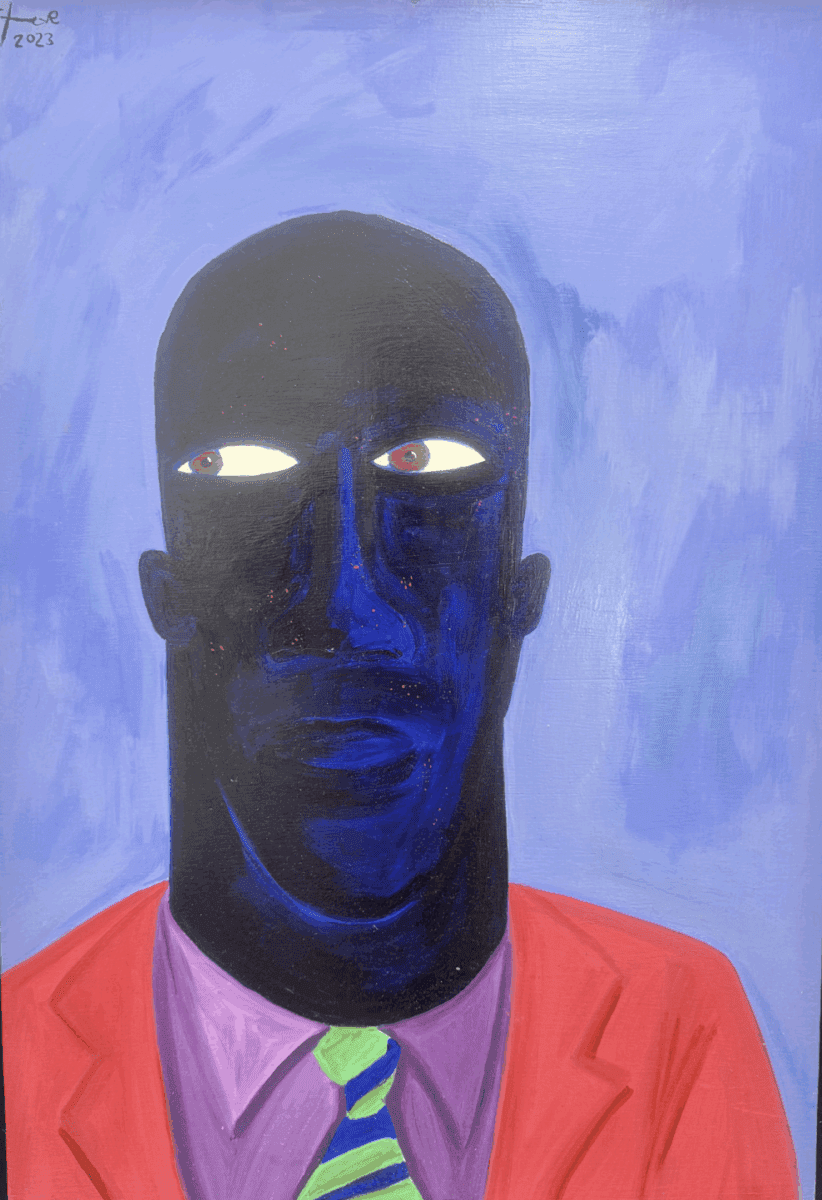

3. Stephen Anthony Davids, I AM MY FATHER, 40 x 50 cm, displayed at White & Case.

4. Stephen Anthony Davids, SELF PORTRAIT (SIDE EYE) MAN IN PINK SUIT, 63cm x 87cm, displayed at White & Case.

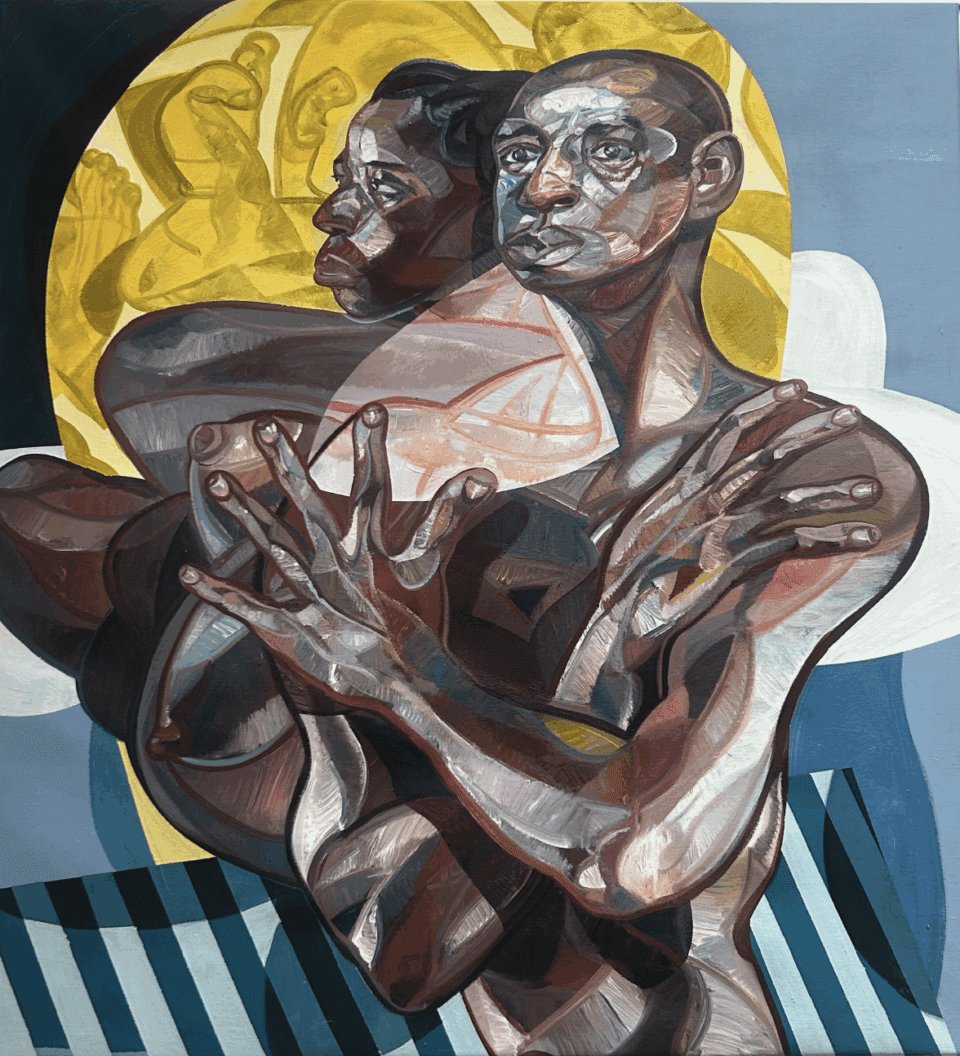

6. Nigatu Tsehay, Echoes of the Unseen I, 2023, Signed on Verso, Acrylic on Canvas, 101 x 93.5 cm, displayed at White & Case.

7. Nigatu Tsehay, Echoes of the Unseen II, 2023, Signed on Verso, Acrylic on Canvas, 110 x 94 cm, displayed at White & Case.

8. Christian Hiadzi, QUIET SENTIMENTS, Acrylic on canvas, 120 x 115, displayed at White & Case.