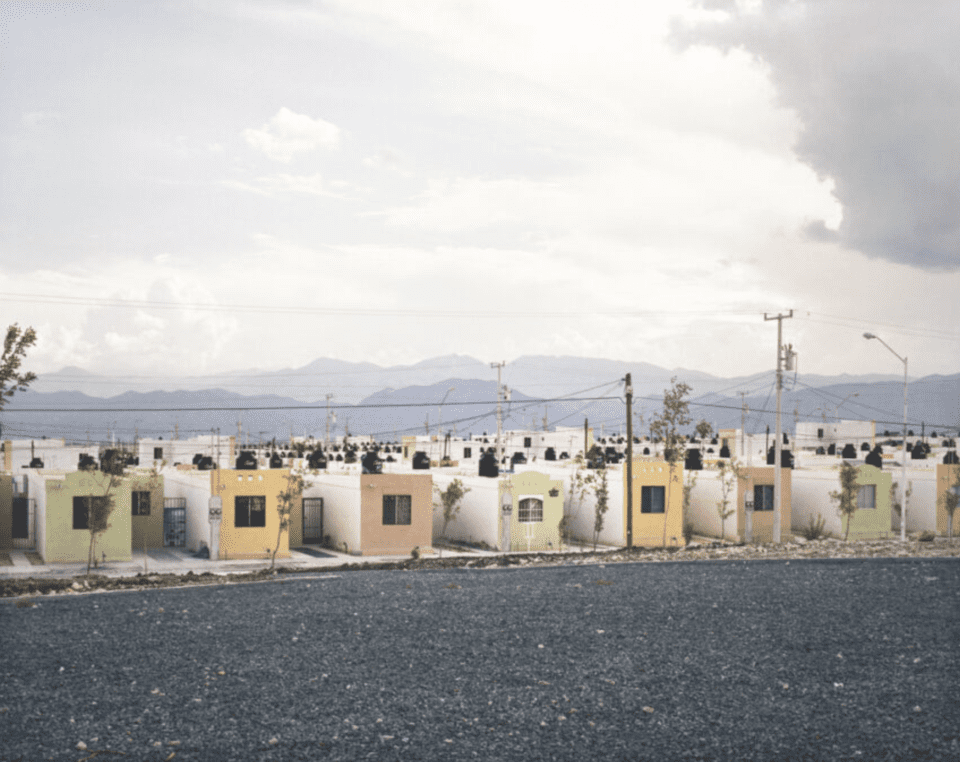

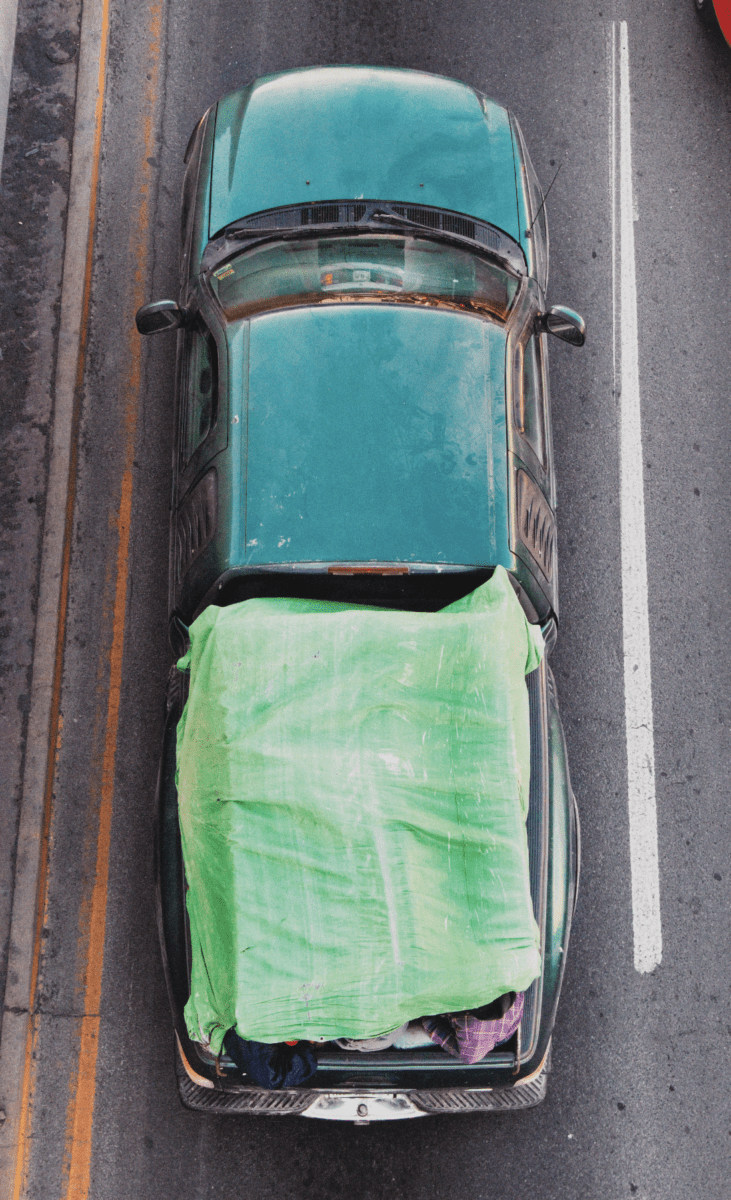

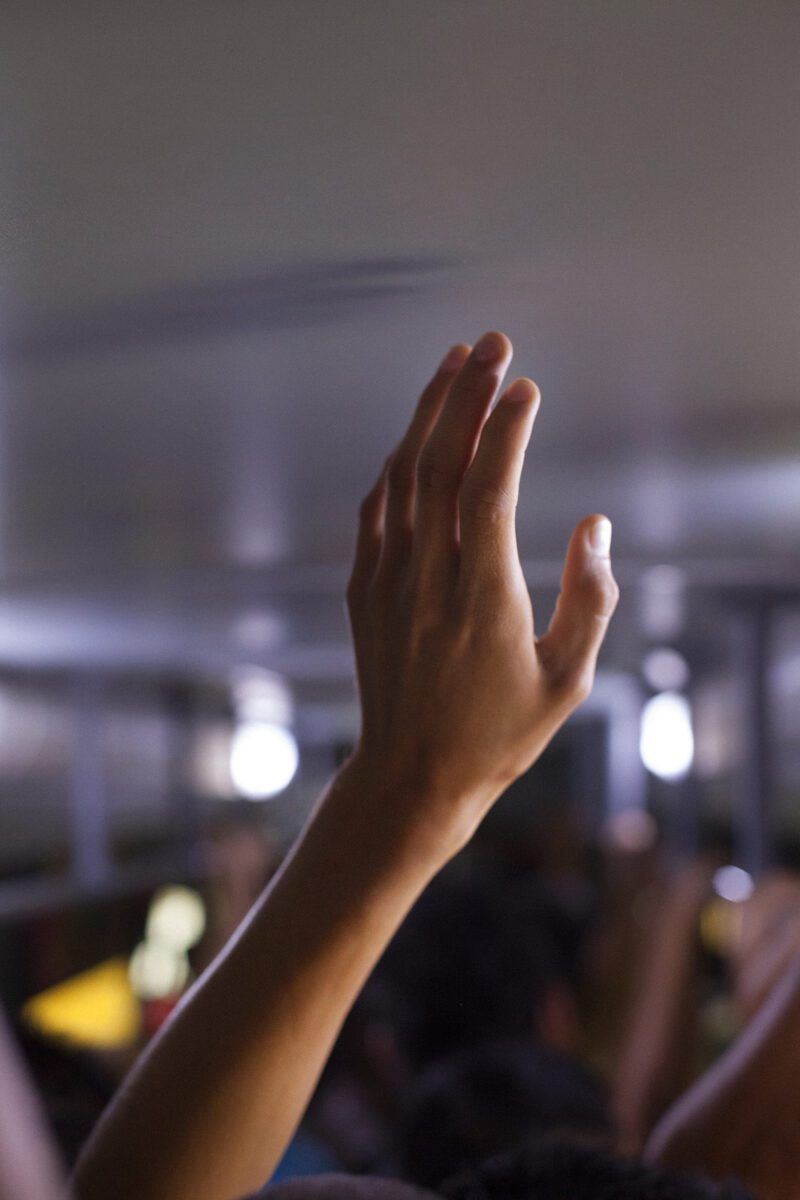

The US-Mexico Border. Suburban sprawl. Wealth disparities. These concepts are subject of photographer Alejandro Cartagena (b. 1977). The prolific artist, originally from the Dominican Republic and now based in Mexico, employs landscape and portraiture to examine social, urban and environmental issues. He uses a vast array of formats and techniques, from documentary and collage to the appropriation of vernacular photographs and AI-generated imagery. There is a political decisiveness to his practice, prompting viewers to question to the systems that shape our world. They’re rooted in Mexico, and each image has a distinct sense of place, but his series speaks to shared global conditions of migration, environmental crisis and unchecked development, offering a powerful reflection on the broader forces defining life in the 21st century. Carpoolers (2014 – 2024), documented the commuters of Monterrey, often piled into the back of pickup trucks, whilst Deutsche Börse-nominated series A Small Guide to Homeownership (2020) exposes the dangers of urban growth through an ironic “how to” guide to buying a home. Now, SFMOMA presents the first major retrospective of the artist, bringing together two decades of his work. Cartagena sat down with Aesthetica to discuss the show, his creative process and what the future of his practice looks like.

A: Take us back to the start. How did you start working behind the lens?

AC: I came to photography through photo albums. My family moved from the Dominican Republic to Mexico when I was 13 and I felt an urgency to maintain a connection with my past. The family’s photo albums became a place where I could go back and rebuild stories. That experience sparked an obsession with the idea that photographs don’t just show the world; they produce meaning, memory and myths.

A: Between Borders, Americanos and Without Walls are a trilogy of projects that explore the US-Mexico border. How do these works push back against simplistic narratives of south-to-north migration?

AC: I came to these “stories” because they are part of where I live and of the people, places and events that shape me. The border is often reduced to a single storyline, but it’s a complex lived geography with tangible infrastructure and a large amount of invisible forces – cultural, economic, social and political – that push and pull us in multiple ways. That’s why the trilogy moves through different “chapters” of the same border, in order to propose other kinds of narratives. These projects insist that migration is not only south-to-north, or that what happens there is just illegal immigration, violence and drug trafficking. It’s also about emotional hardships, family, construction and loss of identity, hope and vulnerability.

A: How do you navigate documenting political and social topics at a time when, both in the US and globally, the landscape is constantly shifting?

AC: I try not to photograph the news cycle. I capture the conditions and phenomena that outlast them: borders, housing, land use, labour and the ways policy becomes visible in ordinary space. The instability of our world is not something the camera can solve; it’s an instrument that helps us better understand these complicated spaces. In addition to this, we’re also living through a crisis about what images mean. What is real, what is fabricated, what is believable? In that context, photography’s value is in being in front of something and being accountable to it. Today, because of where we are with the state of the world, we need to reinvigorate the documentary side of photography more urgently than ever.

A: Carpoolers, which documents commuters getting to work without reliable transport or public infrastructure, really struck a chord with people. Why do you think that series has been so popular?

AC: I honestly don’t have a simple answer. I think there are many things at play. Viewers tend to project different stories and ideas onto the images: from class, labour conditions and migration, to a bit of nostalgia. It is amazing how the work accommodates so many interpretations. Importantly, the fact that it is a series helps build the personal relationships that people have with the stories they see in the images.

A: You often focus on series over singular images. What does a collection of works allow you to express that a single photograph cannot?

AC: I tend to think that a series allows contradictions. A space for the viewer to think. Seriality allows you to examine a subject from multiple angles, keeping the work open-ended rather than heavy-handed.

A: Environmental change runs through your work. Do you think photography can still shift how we respond to climate crisis?

AC: Photography can’t replace policy, but it can change what feels normal. I’ve spent years looking at how land is used and abused, culture is built through space and environmental consequences are hidden inside stories of “development”. When you show these patterns not as spectacles, but as lived landscapes, you can disturb the stories we tell ourselves about progress. This kind of impact might also come from exhibitions, projects or books – cultural objects that slow down attention and connect climate to unexpected themes like housing, inequality and labour, rather than treating it as an isolated issue.

A: You said that “photography changed our world two centuries ago.” Does it still have the power to transform how we interact with our modern world?

AC: I’d argue that it still has that ability. Think of reactions to those photographs of White House staff by Christopher Anderson for Vanity Fair a few weeks ago. Simple, strong shots that created visceral reactions. People understood the larger meaning through the images themselves; no need for the photographer to give us a page-long statement about what they represent. That being said, photography is in an imminent crisis because of the proliferation of AI. These tools raise the question of why we still need photographic images. I have many ideas about the answer, but the fact we are asking feels important.

A: Why do you choose to incorporate AI into your practice?

AC: Generative AI has created a crisis for photography, especially for the public’s idea that “photograph equals proof”. I’m excited by this problem, because it forces better questions: why do we make photographs now? What do they do that other images cannot? My interest in AI reflects my interest in how images have created the visual structures we operate in today. These models learn by studying millions of human-made photos and extracting conventions. It forms an understanding of how we “think” a landscape looks or how we “think” a face is aesthetically built. In that sense, AI images are strange mirrors of humanity. They come from our visual culture. They can expose our biases, our habits of seeing. I’m not using AI to replace photography, but to interrogate it: to understand how images are made, believed and how that affects us.

A: Do you have a particular image or series that stands out as a particular favourite?

AC: I’ve told the curator, Shana Lopes, many times that what hit me the hardest about the show was the way the different projects connect with each other. I’m seeing work that I had never seen together in the same space. I started finding more links and recurring obsessions that have been with me since the start.

A: What would you like people to take away from visiting the show?

AC: If the exhibition works, it doesn’t tell you what to think about my observations. It leaves you more alert to how images construct belief and makes you more attentive to the systems that organise our culture.

Alejandro Cartagena: Ground Rules is at SFMOMA, San Francisco until 19 April: sfmoma.org

Words: Emma Jacob & Alejandro Cartagena

Image Credits:

1&5. Alejandro Cartagena, Suburban Bus #56, from the series Suburban Bus, 2016; courtesy the artist; © Alejandro Cartagena

2. Alejandro Cartagena, Suburbia Mexicana, Fragmented City #13. Collection SFMOMA. Gift of the artist and Javier Alvarado, © Alejandro Cartagena.

3. Alejandro Cartagena, Carpoolers #50, 2011-2012. Collection SFMOMA. Purchase through a gift of Kirsten Wolfe © Alejandro Cartagena.

4. Alejandro Cartagena, Business in a Newly Built Suburb in Juarez, from the series Suburbia Mexicana, 2009. Collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund purchase © Alejandro Cartagena.

6. Alejandro Cartagena, Suburban Bus #16, from the series Suburban Bus, 2016; courtesy the artist; © Alejandro Cartagena.

7. Alejandro Cartagena, Fragmented Cities, Escobedo, from the series Suburbia Mexicana, 2005–10; courtesy the artist; © Alejandro Cartagena.