“I consider the usual aids of self-definition – sex, age, talent, time and space – as tyrannical limitations upon my freedom of choice.” These words, written by Eleanor Antin (b. 1935) in 1974, sum up a career dedicated to exploring identity. The performance artist creates and inhabits alter egos that cross gender, class, geography and historical eras. She refers to these personas as her “selves,” staging them through literature, film and sculpture. These characters frame identity as fluid and performative, rather than adhering to society’s rigid standards. This approach aligns her with key figures of late 20th-century art, including Cindy Sherman, who constructed identities through self-portraiture, and Marina Abramović, a defining force in performance. In a time when identity politics and self-presentation are more scrutinised than ever, Antin offers a poignant meditation on the instability of the self.

Now, her work is on display at MUDAM, Luxembourg. The retrospective is the latest in a long line of solo shows dedicated to Antin’s oeuvre, including at ICA in Boston, Arnolfini in Bristol and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as well as appearing at the 37th Venice Biennial. Her institutional recognition goes back to 1975, when her renowned 100 Boots series debuted at MoMA in New York. Eleanor Antin: A Retrospective marks the first major European survey of her five-decade, multidisciplinary career. Here, the many facets of her practice are brought together, underlining how, by standing at the intersection of conceptual art, performance and second-wave feminism, Antin profoundly shaped the artistic canon.

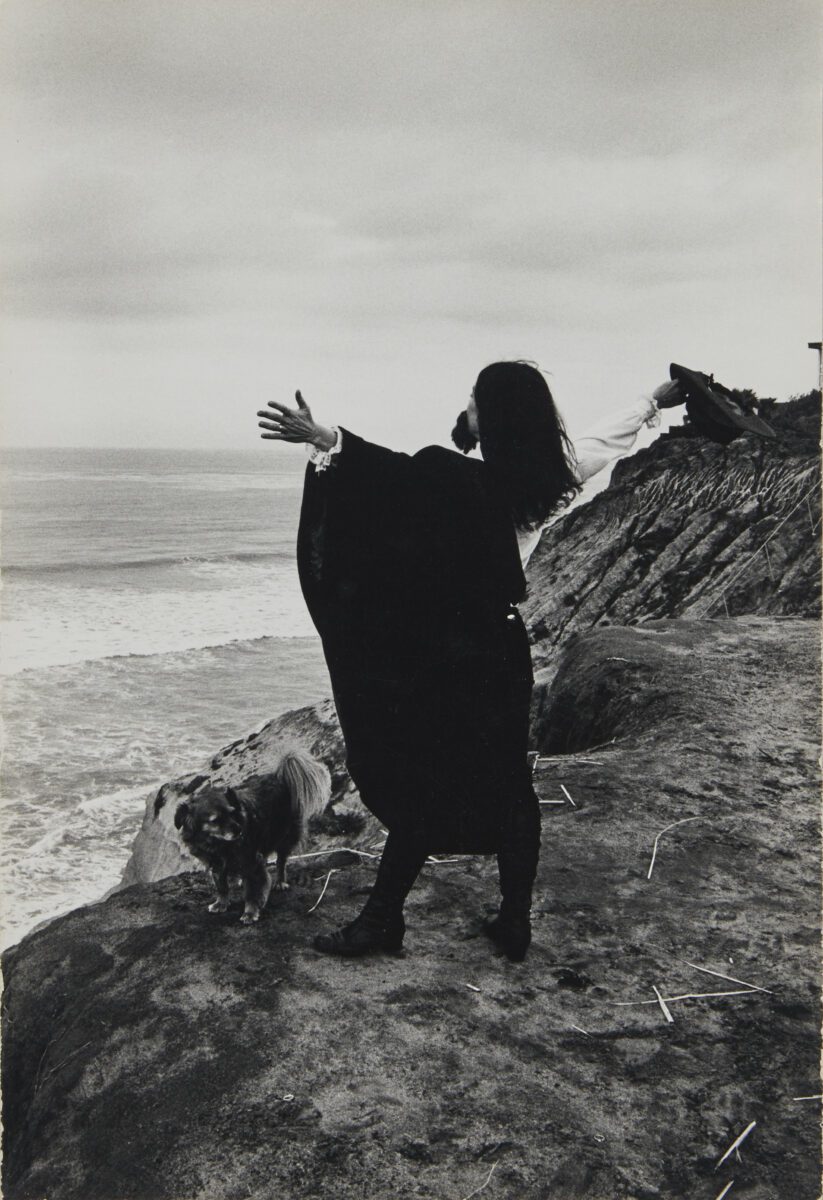

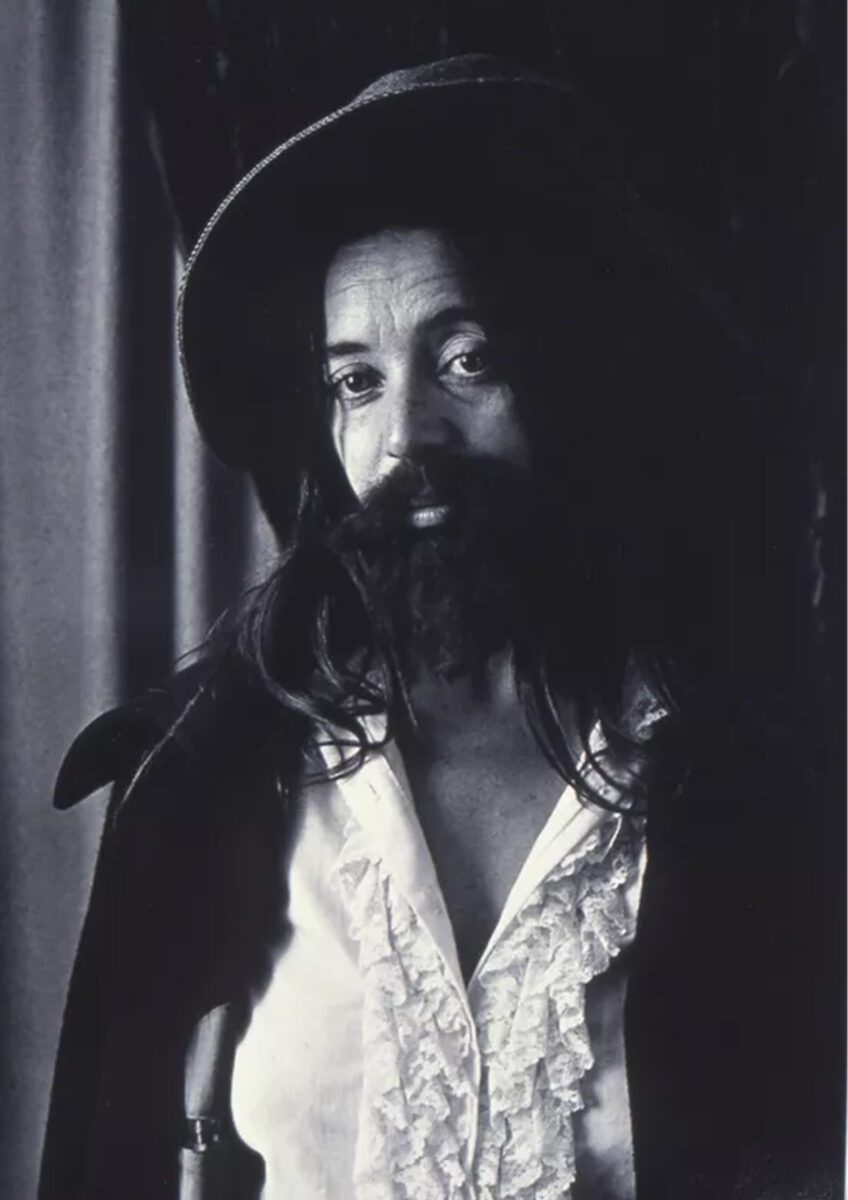

Visitors will encounter several iconic feminist works, in which Antin unflinchingly confronts society’s inherent misogyny with clarity and force. The exhibition’s first section, titled Classification, dissects female bodies and behaviour through the lens of taxonomy. Meanwhile, the following group of works, given the name Admiration, celebrate the overlooked women in Antin’s circle, revealing her connections to Carolee Schneeman, Kathy Acker, Martha Rosler and other women artists active in New York during the 1970s. Another of the gallery’s sections focuses on her archetypal alter ego: The King. The male persona takes centre stage in Power, which Antin uses to deconstruct patriarchal structures and social hierarchies. In one image, titled The King of Solana Beach (1974 – 1975), the artist stands on the edge of a cliff, gazing out to sea. She’s wearing a thick beard and regal cloak – this is The King’s domain and his power feels endless.

CARVING is perhaps the most striking and enduring part of MUDAM’s show, emblematic of her ability to cut across disciplines to create something uniquely powerful. CARVING: A Traditional Sculpture was created in 1972 and comprised 148 black-and-white photographs documenting the artist’s gradual weight loss over 37 days. Antin becomes both sculptor and sculpture, performing the act of self-monitoring, which was a common topic of discussion in the feminist movement at the time. The mixed-media artwork critiques the pressures placed on women to physically conform to narrow beauty ideals by shrinking their bodies to a certain size. It has echoes of the John Berger quote from the same year: “men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Antin returned to the concept in 2017 with CARVING: 45 Years Later, where she recreated the seminal piece. The two are almost identical: she stands naked in shots taken from the front, back, left and right, her hair long and dark. The difference, of course, is that she’s older. In displaying a body with lines, marks and wrinkles, Antin enacts radical acceptance in a society that often shuns ageing women. In an interview with Frieze, the artist said: “The idea of growing old doesn’t have to be some horror. I’ve always found older faces with life on them really interesting. There’s experience on the body, which I realised as I was working on my own body.”

Antin’s oeuvre played a crucial role in shaping the conceptual art movement, which emerged, in part, as a critique of an art market dominated by large-scale paintings and sculptures – often confined to crates, galleries and elite circulation. In contrast, conceptual art embraced immateriality, reproducibility and ephemerality, challenging traditional notions of ownership, value and artistic production. One prime example is Road Movie, which is currently on view in MUDAM’s Grand Hall. It showcases Antin’s iconic 100 Boots: a series of 51 black-and-white postcards sent through the U.S. Postal Service to friends, artists, critics and institutions. In doing this, she transforms the post into both medium and exhibition space, rendering her series of ironic installations widely accessible.

Eleanor Antin: A Retrospective is an impressive tribute to an artist who used her platform to challenge the status quo. The show is rooted in second-wave feminism and the 1970s art scene, where Antin was a dominant voice in conversations about women’s place in a changing world. Yet, her considerations of the female body, representation and the accessibility of the arts feel just as home in conversations had in 2025 as they did more than half a century earlier.

Eleanor Antin: A Retrospective is at MUDAM, Luxembourg until 8 February: mudam.com

Words: Emma Jacob

Image Credits:

1. Eleanor Antin, The Two Eleanors, (1973).

2. Eleanor Antin, Eleanore, (1954).

3. Eleanor Antin, The King Of Solana Beach, (1974-75). Courtesy the Artist and Richard Saltoun.

4. Eleanor Antin, Portrait Of A King.

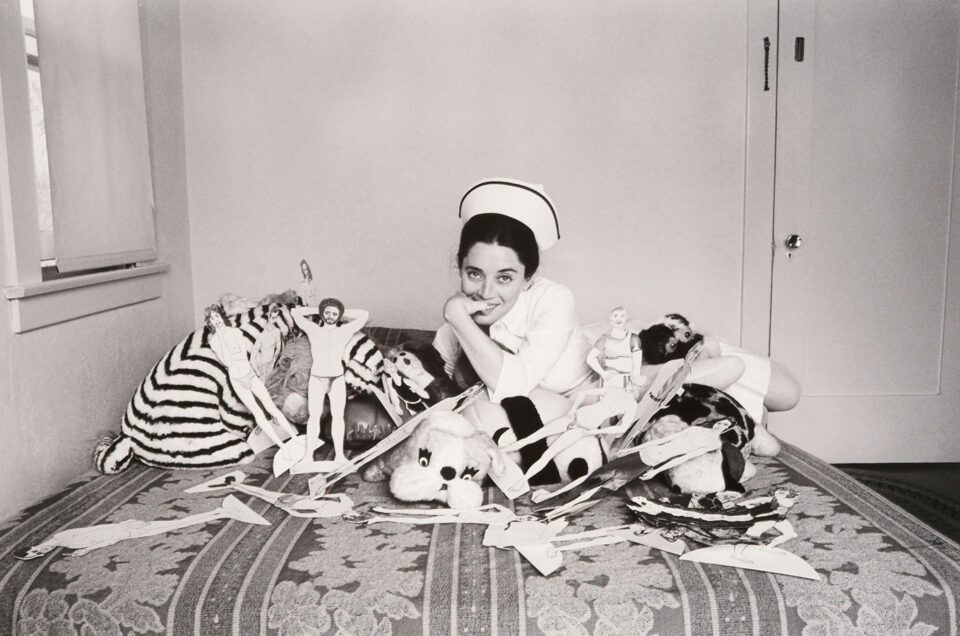

5. Eleanor Antin, Nurse Eleanor RN, (1976).