Yuna Ding is a Chinese cross-media artist, living and working in London. Her signature aesthetic – spanning illustration, installation, digital art and more – is defined by muted colour palettes and a soft focus, pastel-like finish. Yet beneath the delicate visual language and playful aesthetic lies an astute cultural critique, probing the “soft violence” embedded within family structures and social expectations. It’s an approach that has captured audiences globally, with exhibitions in Beijing, London and Paris.

Love to Fish (2023), for example, reflects on a problematic dynamic between romantic partners, using apples – the biblical forbidden fruit – as a conflicted symbol of love and lust. These surreal compositions, rendered in pale pinks and various shades of red, tell a story of control, danger, desire and power. Apples replace human faces, becoming mask, companion and captor. Here, the subversive cuteness of Yoshitomo Nara meets the enigmatic visions and mythical creatures of Leonora Carrington, or Dorothea Tanning. This is just one example of Ding leveraging what she calls “soft image politics” – converting vulnerability, emotional labour and conflict into visuals that are gentle, yet incisive and thought-provoking.

Other recent works include Identity of Yuna (2024). The idea for the project came after the artist cut off a clothing label, which included key information about the garment: its material, washing instructions and where it was made. “As the label seemed to define the identity of the clothes, I began to think about my own identity,” she recalls. The result is a collage of moments and memories that make up the tapestry of her life: from “sewing” and “bento”, to “insomnia” and “passive smoking”. It’s a testament to the raw and deeply personal quality that sets Ding apart. This is an artist who is unafraid to lay themselves bare – much like Tracey Emin, who was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1998 for the then-controversial My Bed.

This summer, Ding’s unfiltered approach saw her featured in She Looked Back, a group exhibition at Purist Gallery, London, that challenged the notion of “female identity” as a fixed label. The show portrayed womanhood not as a monolith, but as a dynamic, complex process that is constantly shifting. As such, it was the perfect backdrop for Ding’s paintings, which were described as “the exhibition’s most candid and raw personal archive.” They follow the artist through key stages of life. Child depicts the moment her personality began to take shape. Girlhood captures when “the concept of femininity was superimposed” upon her. In Wife, she navigates the realities of a difficult relationship, before Mom confronts the profound challenge of maintaining self-value and fulfilment amidst the demands of family life.

Motherhood has become a major throughline in Ding’s practice. Following the birth of her child, she experienced postpartum depression and neurosis. Now, as a parent to a nine-year-old, she’s interested in how art can foster healing – transforming her personal experience into something tangible. She organises workshops for mothers and is committed to wider societal change, particularly in areas such as mental health, maternity care for immigrant women and gaps in the UK healthcare system.

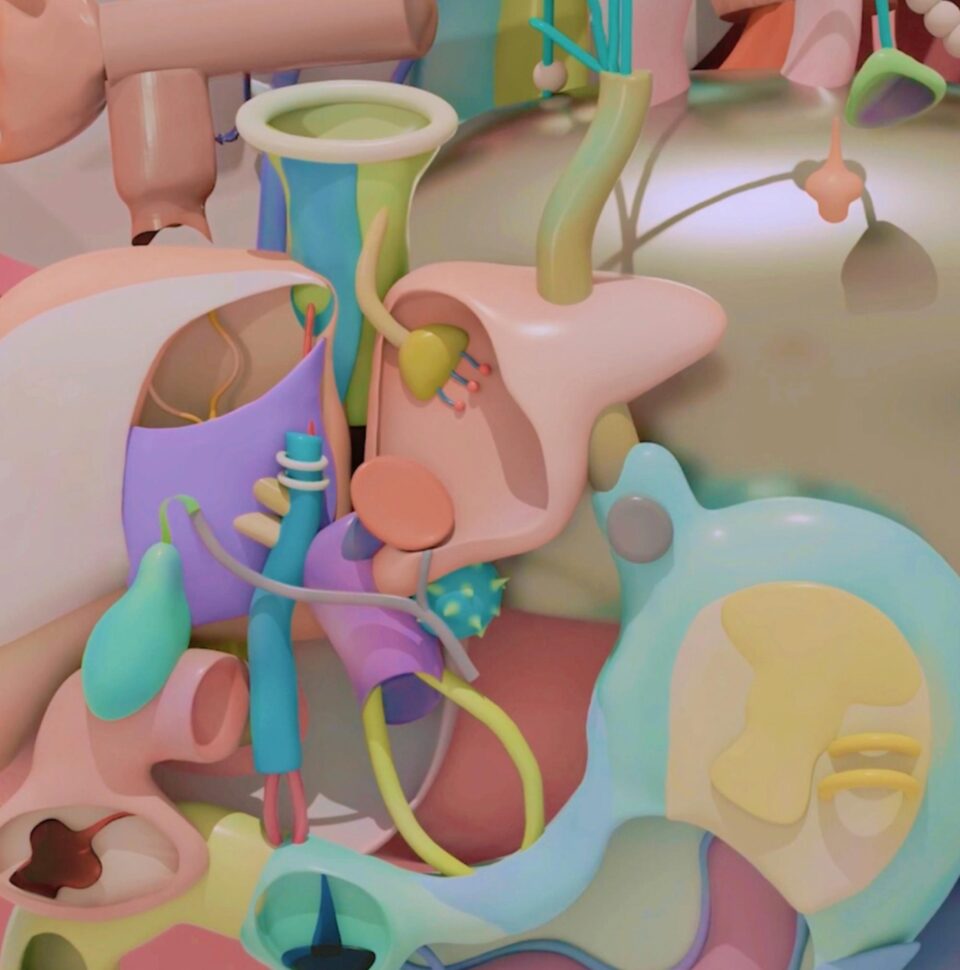

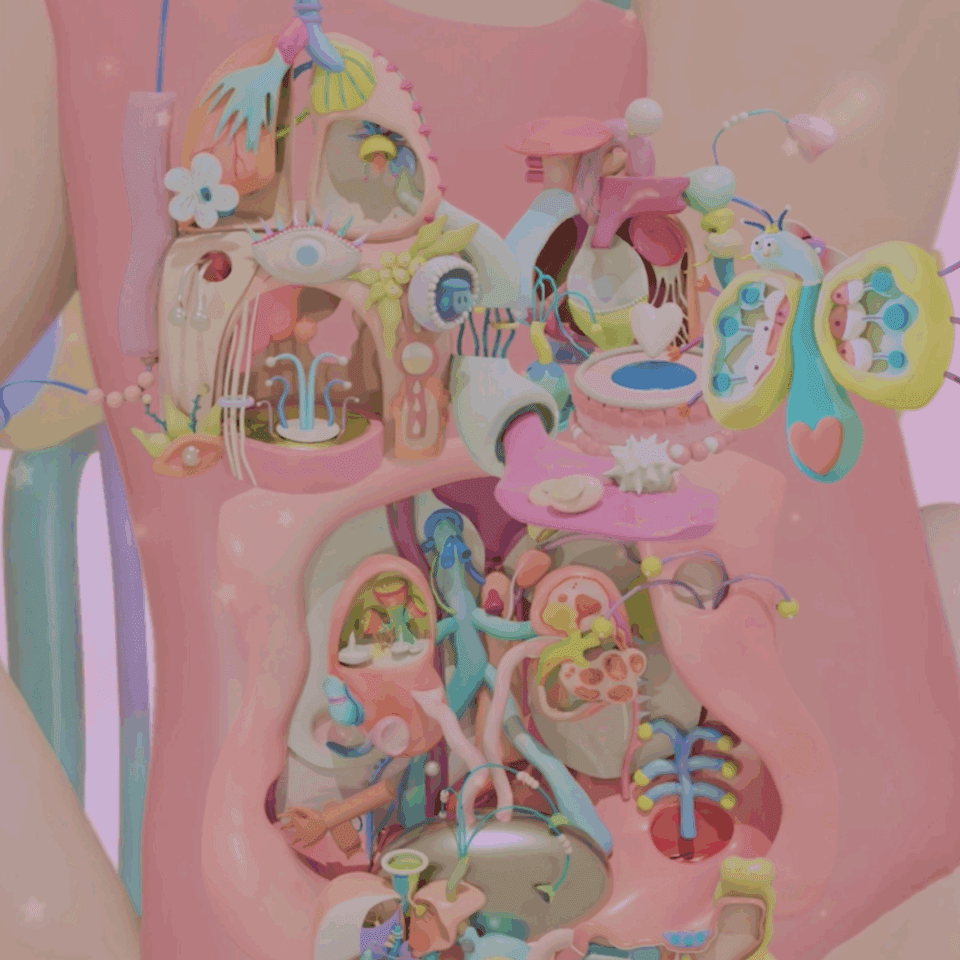

Many of Ding’s works offer a critique of “mother” as a gendered structural symbol. Her most recent piece, WARMENG (2025), is no exception. It is an ambitious digital art piece that employs 3D illustration, moving image and sound to construct a virtual representation of the body. The piece may call to mind Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490 – 1500); it’s a similarly crowded, dreamlike composition, where pink forms sprout flowers and the grotesque intersects with the beautiful. Elsewhere, WARMENG’s toy-like proportions evoke a doll’s house or child’s playset. Whatever the association, the work is designed to visualise “happy hormones” – mapping the symbiotic relationship between organs and emotions. Here again, Yuna Ding subverts intimacy, soft aesthetics and pastel tones as critical tools, prompting viewers to consider the weight of structural pressures – sometimes before they even realise it themselves.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits:

1. Yuna Ding, Love to Fish, (2023).

2. Yuna Ding, WARMENG, (2025).

3. Yuna Ding, WARMENG, (2025).

4. Yuna Ding, Love to Fish, (2023).

5. Yuna Ding, Love to Fish, (2023).

6. Yuna Ding, WARMENG, (2025).

7. Yuna Ding, WARMENG, (2025).