Photographer Mária Švarbová (b. 1988) is best known for her memorable Swimming Pool portraits. The shots, which rely on symmetry and geometry, position athletes in brightly coloured costumes against stark indoor recreation spaces. Švarbová’s images have gained significant traction over the past eight years, winning the Hasselblad Masters Award in 2018. She made the Forbes 30 Under 30 whilst garnering 400K Instagram followers since they were published in 2014.

The subject of the bather is well-established in art history, with famous examples including 19th century paintings like Bathers at Asnières by Georges Seurat (1859-1891) and Paul Cézanne’s The Bather. Later, David Hockney’s (b. 1937) A Bigger Splash became an icon of pop art and California cool. In fashion photography, red and blue swim caps and beach settings can be traced back to a 1949 shoot by Clifford Coffin (1913-1972) for American Vogue, or works by Louise Dahl Wolfe (1895-1989) and Martine Franck (1938-2012).

The architecture of vintage leisure spaces continues to be celebrated in contemporary work. In 2019, V&A, London, launched Into the Blue, whilst the Annie Kelly’s book Splash (2019), published by Rizzoli, took a wider look at the movement across the world. Other photographers transfixed by the minimalist shapes and clean symmetry of lanes include Brad Walls (b. 1992), whose award-winning aerial views of outdoor pools are taken using new imaging technologies.

Yet Švarbová seems to deviate from the idyllic, sun-drenched appeal of many influenced by mid-century works. Instead, figures stand stoic and controlled against the unsettling emptiness of minimalist architecture. These compositions evoke a sense of nostalgia and timelessness, but the focus on uncanny, abandoned locations feels distinctly modern. Images of grand, disused buildings are more popular than ever, with artists like Reginald Van de Velde (b. 1975) at the forefront. Most notable here is his book Between Nowhere & Never (2015), whilst Gohar Dashti (b. 1980) explores nature’s persistence in the face of human displacement, with Home (2017) revealing plants carpeting tiled floors and climbing staircases. The works capture forgotten and deteriorating buildings and reverberate with both unease and fascination.

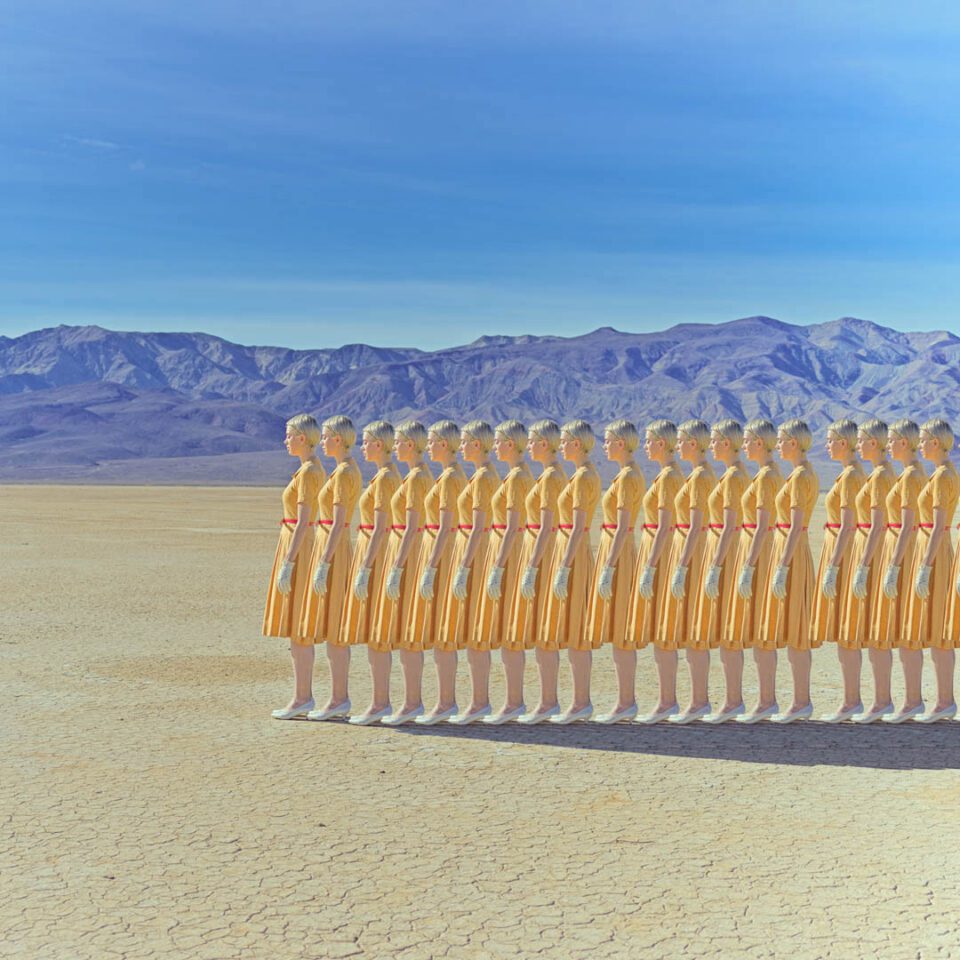

Švarbová combines the polished landscapes of the 20th century and the eeriness of contemporary, abandoned photographs in her latest series, which consider new forms of composition. She translates the symmetry of lane lines to parallel figures in corporate office spaces, whilst open mountainscapes depict solitary figures on empty tarmacked roads. Throughout, Švarbová manages to bridge the gap between the idyllic and derelict in scenes that use desolate environments as an allegory for human vulnerability. Now, a land- mark exhibition of her work appears at La Térmica, Malaga.

A: Your style focuses on experimentation rather than traditional portraiture. Can you discuss your influences?

MS: At the beginning of my career, I took a lot of expressive portraits. I developed gradually, working on photography that harmonises the space with the subject. My greatest influ- ences are architecture and design. I am fascinated by modern practices – especially Brutalism. This style, which emphasises minimalist, bare buildings and structured designs, provides me with the opportunity to craft scenes from these sterile and rigid spaces. My experiments extend to models as well as their environment – the human form fascinates me as much as the space they inhabit. I make the subject and en- vironment form one cohesive whole with curated structures. That’s why I prefer to shoot in built spaces, so I can discover and record these relationships. Lost in the Valley breaks this rule, but there are still lingering elements of humanity.

A: Early series, like Human Space (2015), draw upon more surrealist, dreamlike narratives than your recent work. How has your interest in Surrealism changed?

MS: My work hasn’t been influenced by Surrealism in eight years. Whilst some images maintain the dreamy, whimsical tone of my earlier works, the themes I examine are limitless – they’re not defined by the surreal. I am inspired by childhood memories, which often transfer into my work. The Butcher (2015) was created in this way. For example, Anna (2015) is reminiscent of a fragment from my past. It depicts a young girl in a red scarf and ponytails behind the counter, recalling how I played at the sales office behind the cash register. This girl appears several times – watching a couple’s embrace, covering her face with a tissue, sitting on the butcher’s counter. This retrospection informs my work. It is genuine authenticity that cannot be fabricated.

A: How does your focus on people performing routine actions relate to the idea of representing daily life?

MS: I want to concentrate on the day-to-day. The Butcher, Dining Room and The Marriage, amongst others, all illustrate people’s ordinary activities to highlight the realities of life. In Married Couple (2014), a couple stand next to each other, staring expressionless into the camera. I con- sider these my Plastic Worlds because the models do not act like living, moving subjects: they are figurines. By taking away emotion and allowing them to stand frozen in time- less poses, I create an environment that invites onlookers to stop and inspect the scene – and, consequently, to look inwards at their own feelings. As they attach their own associations, their imagination becomes part of my work.

A: Lost in the Valley (2019) showcases lone figures staring bleakly in front of empty mountainscapes. Can you describe this body of work in more detail? How did this remote, natural environment influence the series?

MS: These subjects are stranded, and not just in the literal sense. Throughout, participants are lost not only in location but in their souls. There isn’t one interpretation. You can look at the woman in Blue (2019) and perceive loss, nostalgia and melancholy. However, there is hope too – for discovering a better tomorrow and finding yourself. It’s important to have that balance, and this natural setting offered a new perspective. In later works, such as Fragile Concrete (2021), I reconcile these influences: concrete architecture complements the natural, vast blue skies and sea view.

A: What is the significance of the nostalgic atmosphere you evoke? How do you conjure this particular mood?

MS: It’s almost futuristic. The energy needs to be right. Ambience is characterised through bright spaces and daylight, contrast against these expansive architectural structures. The props, the colours, the location – these are all informed by the subject matter. I’m creating a narrative, so I follow the scene and let my personal emotions influence the over- all composition. There’s this tension, this excitement, that dictates the path for me. I know the scene is working when I catch myself photographing the same elements over again.

A: You studied archeology at university. In what ways do you think this has influenced your photography?

MS: I studied at Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Slovakia. It was a difficult subject, but I still use the practical and life skills I learned in my photography. I’m disciplined; I know that when I start a new project, I will complete it to the best of my ability. I also love combining different artistic disciplines, using them to create something new and interesting. Archaeology first inspired my Swim- ming Pool series. I used this knowledge to compare different interior structures, which informed the final locations.

A: Your more recent works use outdoor environments. Thinking back, how were you drawn to swimming pools?

MS: The location of the first pool I photographed was in my hometown of Zlaté Moravce in Slovakia. I was supposed to take portraits of swimmers. However, when I saw the architecture of the swimming pool – the cream tiles, the symmetry of the design, the perfect lighting – I forgot all about them. Instead, I started filming scenes and taking photos of the geometric shapes and the swimmers. I was fascinated by the clean lines and minimalism. I created a visual adventure that represented the concepts I truly value: harmony, uniformity and balance. In my personal life, I curate my possessions and search for this sense of equilibrium with the objects around me. It felt natural for this to impact my photography, so this was a hugely influential moment.

A: After your seminal Swimming Pool, you made Forbes 30 Under 30. How did it feel to achieve this recognition?

MS: It was such an enjoyable experience. I fell in love with photography, so it was brilliant to receive that kind of positive response for my work. I am now collaborating with Forbes Slovakia on the Forbes DNA campaign, which questions what qualities create successful people. Everyone is capable of making the 30 Under 30 list – these opportunities are available to anyone who works hard, is passionate and doesn’t give up. Perseverance is the key to success.

A: How does the title of your exhibition at La Térmica, This Is My Swim Lane, encompass all your projects 2010-2022? What can we expect from you in the future?

MS: I love the name. It’s a great play on words in English. Whilst I’m known primarily for Swimming Pool, which remains my largest ongoing concept, the idea of a Swim Lane shouldn’t be taken literally. The show investigates how my photography started, but it also highlights the changes that have occurred over the last decade. So, it doesn’t refer to the pool but to the photographic – and life – lane that I am following since that first experience in Zlaté Moravce. I must praise the curator, Dumia Medina, and everyone involved in the organisation of the exhibition. I’m also currently preparing for another solo exhibition in Seoul, Korea, which opens this December. Whilst I can’t say much about upcoming projects, I am excited about them. You can expect to see new works from me throughout 2023.

Words: Megan Jones

This is My Swim Lane | La Térmica Diputación de Málaga Until 12 February

Image Credits:

1. Mária Švarbová, Enigma (2021). From Fragile Concrete. 90×120. © Maria Svarbova for Kolektiv Cité Radieuse, with the kind authorization of Le Corbusier Foundation © FLC I ADAGP Paris 2021.

2. Mária Švarbová, Melancholia (2021). From Fragile Concrete. © Maria Svarbova for Kolektiv Cité Radieuse, with the kind authorization of Le Corbusier Foundation ©FLC I ADAGP Paris 2021.

3. Mária Švarbová, Origins (2019). From Lost in the Valley.

4. Mária Švarbová, Stairway (2022).

5. Mária Švarbová, Blue (detail) (2019). From Lost in the Valley.