Lebanon recently marked fifty years since the outbreak of Civil War in 1975. The conflict was driven by sectarian violence, class struggle, foreign interference and invasions, and its aftermath changed the face of the nation. It lasted 15 years, cost 150,000 lives and led to the exodus of almost one million people. Lebanon was controlled by Syria until 2005, whilst Israel occupied the south of the country until 2000. The decades since have seen economic and political turmoil frequently rear their head, whilst violence in the region throughout June 2025 has caused anxiety about the future of the country’s stability. Photographer Randa Mirza was born in 1978, three years into the Civil War, and her earliest childhood memories were of bomb shelters and violence. Her artist career has been dedicated to reflecting on the nation’s history, shared trauma and collective memory. A new exhibition at Fotomuseum Den Haag is the culmination of two decades of photographic inquiry. The show spans eight series, examining what it means to be Lebanese and charting the dramatic changes that capital city of Beirut has undergone. Aesthetica spoke to the artist about her work, the ways that her early experiences shape her practice and how she sees the role of the camera in documenting national history.

A: Tell us about how you first started working behind the lens.

RM: My first photographs involved portraits and nudes of my friends. We did it for fun but we took ourselves very seriously. Back then, I was doing travel photography, working as a lifeguard in the summer and saving money to cover my travel and film expenses. I did wedding and events photography for a short while, as well as a lot of documentary work with humanitarian organisations and ecological militant groups in Lebanon and France. I also shot music concerts, theatre and dance shows produced by my artistic friends, and briefly worked for newspapers and architecture firms. I did almost every kind of photography except fashion and advertising, whilst simultaneously developing my artistic practice.

A: Beirutopia at Fotomuseum Den Haag spans 25 years. How did you stitch together such a wide body of work into a single show?

RM: The exhibition consists of eight series created between 2000 and 2025, and each one has a specific visual language and approaches a different topic. The thing that links them together is that they are all speaking about the lingering effects of violence – whether it be economic, political or conflict-based. They tell the history of Lebanon starting from the end of the Civil War up until the recent national collapse. The show passes through the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah; the Beirut port explosion in 2020; the coronavirus pandemic; and a financial crash that impoverished 80% of the population. Recently, I started working on images of the systematic destruction of homes by the Israeli army in southern Lebanon, reflecting on the idea of loss and resistance. I think of the exhibition as a puzzle. All the pieces were already there waiting for me to connect them together, in order to construct the whole picture. They are different chapters of the story of the political upheaval and transformation that took place in Lebanon in the last quarter of a century.

A: You describe a formative childhood memory of your mother urging you to run under bombs without looking back. How has this experience shaped the way you view the world, and how you choose to photograph it?

RM: This is one of my most vivid war memories. Our neighborhood was under indiscriminate heavy bombing and my family and I had to flee to a nearby shelter. My mum decided that we would run the 300 metres that separated us from the shelter one after the other. She thought that running at different times would minimise the risk of us all dying together. Several years later, I told this memory to a friend who shared with me a personal comparable story. He and his family found themselves in a situation where they had to decide if they would flee the bombardment or stay at home in a corridor. His mum decided that they should stay where they were and not take the risk of running under the bombs to a safer place. She said to them: “If we are going to die, it’d be better if we die all together.” I think these kinds of intense violent experiences shaped our understanding of urgency, love, life and death. They affect the way we see, and relate to, the world.

A: Your images blur truth and fiction. Why did you choose this over a documentary style?

RM: Rather than depicting reality, my work addresses the traces that war and conflict have left on both collective and individual memory. To do this, I often interweave and question truth and fiction, as well as the relationship between the viewer, image and person behind the camera. This style of photography allows me to alter the audience’s point of view and question the ways images are generally produced and received. I see photographs as a construction of reality, rather than a representation of it. I am interested in what pictures hide and how hegemonic narratives are constructed through images in order to blur reality. My aim is “bringing to light what is forgotten or intentionally hidden.” In other words, I want to deconstruct dominant imagery to unveil propaganda.

A: How do you view the role of artists and photographers in preserving national history?

RM: I come from a place where there has not been a consensus on how we narrate our national history. The lessons taught in schools stop at the country’s independence from the French mandate in 1943. Different narratives are taught depending whether you belong to a certain religious, political, ethnic or social group. This creates a shattered population within a single nation, but at the same time I find it enriching to always be confronted with the possibility of doubt and questioning. As we all know, history is written by the winners. We can only look at it more objectively after decades. By then, it has already become fiction.

A: In Abandoned Rooms, you photograph interiors left behind by displaced families during Syrian occupation. What first compelled you to take on this project?

RM: Abandoned Rooms is a series about traumatic memory and amnesia. It features vacant apartments and destroyed villas, hotels, chalets and summer houses. They were used as shelters during the Lebanese Civil War for the people who fled dangerous regions. Numerous local and foreign militias and armies also inhabited these structures, turning them into housing or headquarters. Despite the gradual restitution of properties since the end of the war in 1990, many of these structures remain in ruin. I entered the wrecks with the desire, curiosity, excitement and fear of returning to places steeped in one’s own past. Walking through the intimacy of each room was like an actual visit to the locked chambers of my personal memory.

A: You live between Beirut and Marseilles. How does this dual experience shape your sense of place, memory and home?

RM: Duality is a thread that keeps coming back in my work – whether relating to gender, identity or belonging. I travel back and forth between different point of views, aesthetics and imaginations. Duality for me is not about experiencing two different things at once. It’s about understanding how thought is constructed and how experiences shape mental frameworks. I read somewhere once that if you speak one language, you are one person and if you speak two languages, you are two people. The more people I am, the wider my vision of the world.

A: The exhibition presents utopia as an illusion. Do you think there is still hope for progress and positive change in the future?

RM: My work talks about a speculative, profit-oriented and neoliberal vision of the future that uses the ideal of progress to erase the historic memory of a culture. It is not progress that is questioned here, but how systems of domination instrumentalise humanity’s continuous desire for positive change. Utopias are more urgent then ever; in fact, they are in danger.

A: Memory is central to your practice, both personal and collective. How do you see photography as an act of remembering?

RM: For a long time, I tried to fill the black holes and empty patches of my past with photographic investigations of history, time and space. The images I make are my memories, both real and imagined. I feel that something has been taken away from me and by photographing the world, I am taking it back. It was not only memory that was taken from me, but also places, loved ones, a feeling of safety and the possibility of knowing stability and future projection. Photography becomes a means for reparation.

A: What’s next? What are you working on?

RM: The villages of southern Lebanon – particularly those bordering the occupied Palestinian territories – were almost entirely razed to the ground by Israeli bombing between August and December 2024. Recent reports state that more homes have been destroyed after the ceasefire that took place on 27 November 2024, than during the last year. A few days after the ceasefire, I flew to Lebanon to return to my homeland after several months of war, taking a large-format view camera and some blank film to photograph the systematic destruction of homes by the Israeli army. To shoot with a large-format view camera requires lengthy manipulations before each shutter release, and is therefore akin to an ancestral performance practiced by Arab poets in front of the Atlal – the traces of abandoned homes, worn remains and empty rubble. Home ruins were fundamental pillars of ancient Arabic poetry. In referring to the last vestiges of the built structure, Atlal symbolises nostalgia, love, loss, perpetual change, departure and separation. The ancient act of composing verses while visiting the atlal is defined as “standing before the ruins” or “crying over the ruins”, a ritual of purification and meditation. The photographic act of shooting with a camera thus becomes a poetic ritual of resistance, reconciliation and reparation in the face of the brutality of war.

Randa Mirza: Beirutopia is at Fotomuseum Den Haag until 28 September: fotomuseumdenhaag.nl

Words: Emma Jacob & Randa Mirza

Image Credits:

1&6. The Selective Residence, from the series Beirutopia, 2011 © Randa Mirza, courtesy of Galerie Tanit.

2. Live up to your true nature, from the series Beirutopia, 2011 © Randa Mirza, courtesy of Galerie Tanit.

3. Zonder titel, Room 4, from the series Abandoned Rooms, 2005-2006 © Randa Mirza, courtesy of Galerie Tanit.

4. Apr 17, 2020, at 11-59-05 AM, from the series We promise, we deliver, 2020 © Randa Mirza, courtesy of Galerie Tanit.

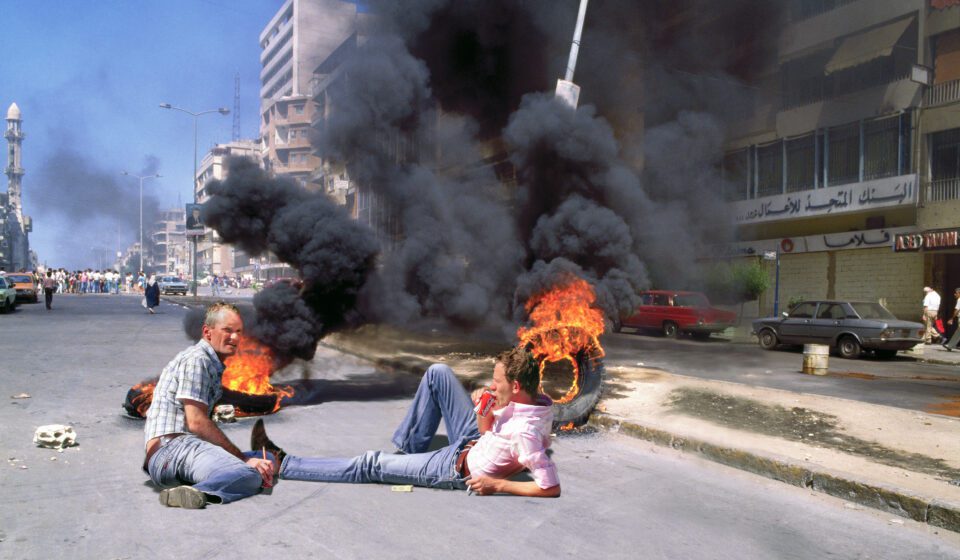

5. Zonder titel No.4 / Cowboys, from the series Parallel Universes, 2006-2008 © Randa Mirza, courtesy of Galerie Tanit.