“If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough.” These are the words of photojournalist and Magnum co-founder Robert Capa (1913-1954). In a rare 1947 interview, he describes putting this into practice for one of his most famous photographs, Death of a Loyalist Militiaman, Cordoba Front (1936). It shows the moment a man was shot down during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Capa recalls being “there in the trench” with the Loyalist men. It’s a controversial image when considering the ethics of documentary photography and the responsibility towards the people behind cameras. Nevertheless, the image preserves a piece of history. Years later, this level of proximity transports audiences back in time.

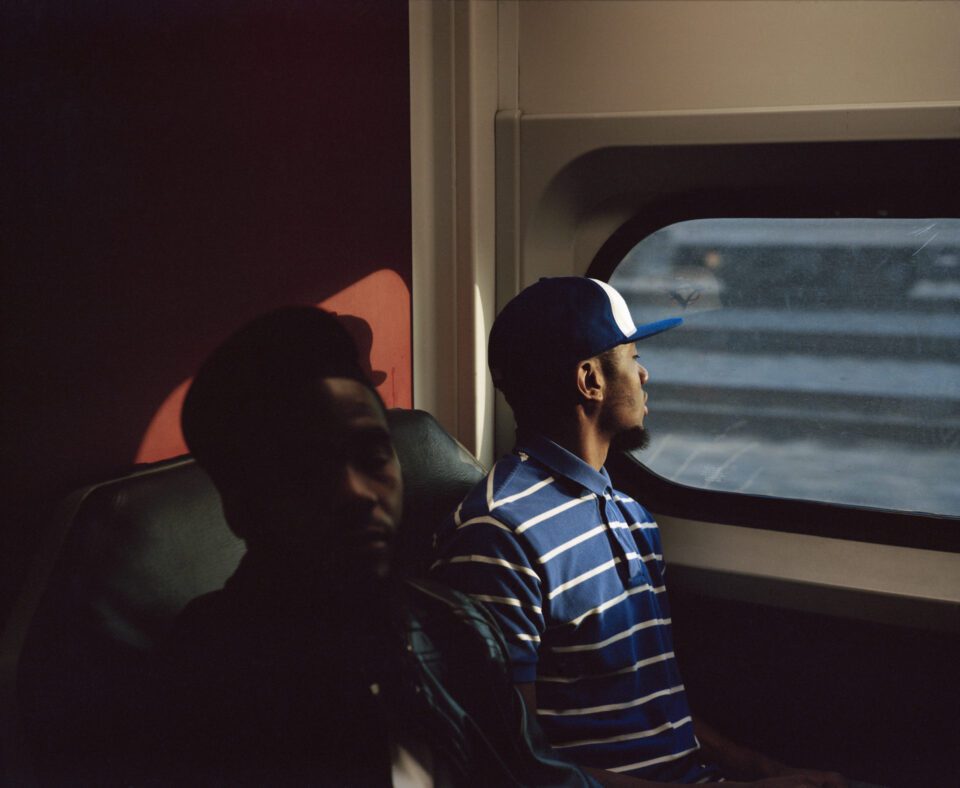

Close Enough is an exhibition guided by this approach to photojournalism. Marking the 75th anniversary of Magnum, Hangar Photo Art Center displays the work of 12 women photographers whose practices follow in the footsteps of co-founder Capa. The collection is united by the ways they bridge the distance between artist, subject and viewer. These are revealing glimpses into people, places and perspectives. For example, Myriam Boulos presents lovers tangled in a passionate kiss; Nanna Heitmann shows us anti-war protests in Moscow and Hannah Price takes us on a peaceful bus ride with dozing commuters. Today, we focus on two standout photographers from the show – Olivia Arthur (b. 1980) and Sabiha Çimen (b. 1986).

We see a figure hunched over with their back facing the camera. Their head is bowed so low that, from the camera’s vantage point, they appear headless. The greyscale scene holds the viewer’s attention as we contemplate the subject’s emotional state. Olivia Arthur’s piece is called Bombay India (2016). The photographer and former Magnum president focuses on people’s lives and cultural identities around the world. This shot is from the series In Private (2016-2018), which began as a project with photographer Bharat Sikka focused on the LGBTQ+ community in Mumbai, India. It eventually grew to encompass all forms of intimacy and sexuality in the city. We see transgender activist Urmi Jadav look at us from one picture. Elsewhere, we make eye contact with a man as he stands in an overcrowded train compartment. Journalist and poet Tishani Doshi reflects on the series and observes that: “The people in Arthur’s photographs look back at us. They hint at ways in which the body can arc back to a more seamless state of being — able to morph into cloud, animal, god, container of both kama and bhakti/eros and agape, Shiva and Shakti/ male and female — a more complete, less shackled version of ourselves.”

Sabiha Çimen, meanwhile, takes us to Istanbul, Turkey. Here, we meet her “creative collaborators”: Seyma, Nehir and Sare. They are sitting on a roller coaster as a plane flies overhead. They shield their eyes from the bright sunlight, surrounded by pastel pinks and clear blue skies. Çimen is a self-taught photographer who travelled around her home country to photograph Muslim schoolgirls studying to become “hafiz.” The term translates to “guardian”/ “memoriser” and is an ancient rite of passage wherein an individual has memorised all 77,430 words of the Holy Qur’an. Hafiz are treated with utmost respect so, since the tradition is mostly upheld by girls, Çimen explains that it is a “rare example of when women and girls can have elevated status in certain Islamic countries.” In an interview with Guardian’s Lydia Figes, the photographer explains: “I wanted to counter the demeaning representations of Muslim women in visual culture, both in the east and the west by showing that these women and girls are not simply bound to the oppressive structures surrounding them.” The photojournalist is amongst a growing number of women challenging these stereotypes by telling their own stories through art. Another example is Muslim Sisterhood, a community and creative agency led by Lamisa Khan, Zeinab Salah and Sara Gulamali that was recently recognised as part of this year’s Vogue Business 100 Innovators. Their work is centred on “reclaiming ownership over images of ourselves and how people perceive us.”

What does it mean to be “close enough”? The ambiguity of the phrase becomes apparent when we see the different ways photojournalists have interpreted the idea. Capa illustrated it by being at the centre of conflict. But, as Arthur and Çimen show, closeness can also refer to more than physical proximity. Is it about the bond between people behind and in front of the lens? Or could it be the split second of intimacy granted when the subject chooses to let their guard down? Close Enough honours all these possibilities. Curator Charlotte Cotton states: “Each photographer openly narrates their creative journey, ranging from reflections upon long-term personal projects to work-in-progress and pivots in their practices. They give personal accounts of their visual vantage points and create a constellation of photographic relativity.”

Hangar Photo Art Centre, Close Enough | 8 September – 16 December 2023

Words: Diana Bestwish Tetteh

Image Credits:

- A plane files low over students riding a train at a funfair over the weekend. Istanbul, Turkey, 29 August 2018 © Sabiha Çimen/Magnum Photos.

- Morning commute on the Septa R5, 30th Street station, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 2009 © Hannah Price/Magnum Photos.

- Adrienne and Zion, Water Valley, Mississippi, USA, 2019 © Carolyn Drake/Magnum Photos.