The Pacific Island of Sāmoa, which lies between New Zealand and Hawaii, recognises four cultural genders: female, male, fa’afafine and fa’atama. The terms fa’afafine and fa’atama translate to “in the manner of a woman” and “in the manner of a man” respectively and are used by non-binary people. Japanese-Sāmoan artist Yuki Kihara is part of the Fa’afafine community. Her visually compelling projects centre and empower these traditional yet marginalised groups, reimagining histories and archives to unpick the effects of colonialism on the region. Now, her renowned series Paradise Camp, which received global acclaim at the 2022 Venice Biennale, is on display at The Whitworth, Manchester. The multi-media series responds to famous paintings of Tahiti and its people by French modernist artist Paul Gauguin. In an act she describes as “upcycling,” Kihara recreates these works in a profound gesture of reclamation. Paradise Camp is displayed alongside a new work, Darwin Drag, which engages with new research into how evolutionary biologist Charles Darwin shaped his findings to wrongly suggest that sexual diversity in animals was rare and unnatural, in order to conform with the conservative values of the Victorian period. Kihara speaks to Aesthetica about her decades-long commitment to recentring queer Indigenous narratives.

A: Tell us about Paradise Camp. How did the work first come about?

YK: It is a multidisciplinary project that considers the intersections of identity, history and colonialism through the lens of Sāmoan Fa’afafine culture. It emerged from my own experiences as a Fa’afafine, as well as the socio-political context of gender diversity in the Pacific. The work combines archival research, performance and visual art to challenge western-centric narratives and reclaim Indigenous perspectives. It also examines the impact of colonialism and tourism on Sāmoan culture, using camp aesthetics to critique and subvert these dynamics.

A: You’ve been empowering the voices and experiences of the Fa’afafine and Fa’atama in Sāmoa for over 20 years. Can you describe the process of collaborating with these communities?

YK: As a Fa’afafine, I’ve created much of my work alongside Fa’afafine and Fa’atama communities. This has been a deeply personal and ongoing process that begins with building trust and fostering open communication. I approach every collaboration with respect and a willingness to listen, recognising the invaluable knowledge and perspectives each person holds. Together, we co-create projects that reflect their lived realities, often drawing on shared cultural heritage and addressing contemporary issues. It is rooted in mutual understanding and commitment to amplifying marginalised voices. My art is also informed by my role as the co-editor of Samoan Queer Lives, a book that documents the diverse experiences of Fa’afafine, Fa’atama and LGBTQIA+ individuals. This has further deepened my knowledge of the complexities within these communities and has influenced my approach to collaboration, ensuring that their stories are told authentically and with care.

A: What inspired you to reclaim Paul Gauguin’s colonial imagery through a queer Indigenous lens?

YK: Gauguin’s oeuvre has long perpetuated harmful stereotypes, portraying Pacific cultures through a colonial gaze that ignores the lived realities of Indigenous people. As a Fa’afafine, I saw an opportunity to reinterpret his imagery through the lens of Fa’afafine and Fa’atama experiences, reclaiming agency and offering a more authentic representation of Pacific identities. By incorporating camp aesthetics and Indigenous perspectives, I aim to critique the Eurocentric narratives embedded in Gauguin’s work, while celebrating the resilience and complexity of queer Indigenous lives. This reclamation is also a way to highlight the ongoing impact of colonialism on Pacific cultures and to assert our voices and stories.

A: You have talked about repurposing the “landfill” of stereotypical Pacific Island imagery. How do you determine which colonial imagery is worth “upcycling” and which should be disregarded?

YK: I consider several factors. First, I look at the historical and cultural significance of the imagery – does it perpetuate harmful stereotypes or erase Indigenous perspectives? If it has been widely used to misrepresent or exoticise Pacific cultures, it becomes a candidate for repurposing. Second, I assess whether it can be subverted or recontextualised to challenge its original intent. For example, in Paradise Camp, I adapted Paul Gauguin’s colonial depictions of Pacific Islanders by reimagining them through a queer Indigenous lens, using camp aesthetics to critique and reclaim these representations. Lastly, I consider the potential impact of upcycling the imagery. Will it spark meaningful dialogue or contribute to the reclamation of Indigenous narratives? Imagery that lacks this potential or reinforces harmful tropes is better left disregarded in “landfill.”

A: The Paradise photographic series is accompanied by a set of video works that feature a five-part Fa’afafine talk show, and an imagined interview between yourself and Gauguin. What types of conversations does this blending of fiction and history open up?

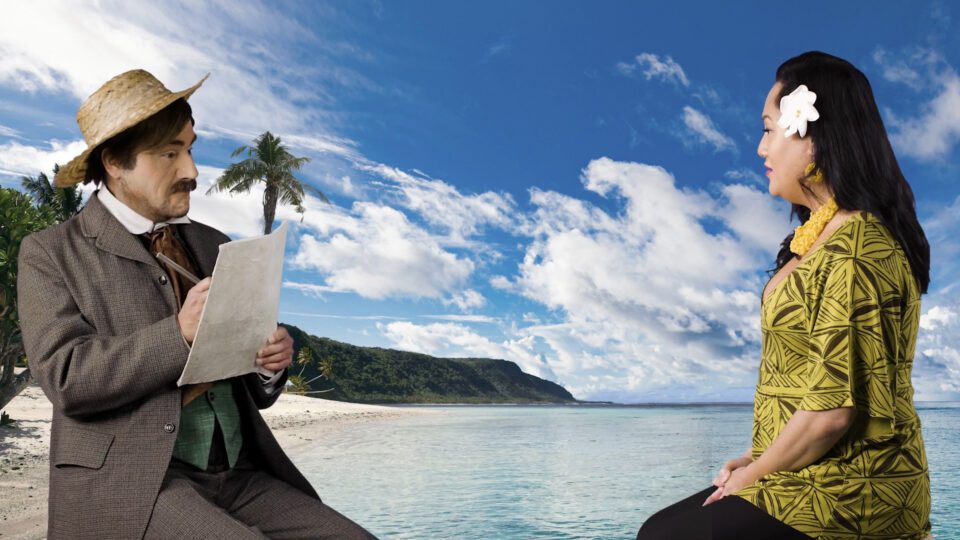

YK: In juxtaposing historical colonial imagery with contemporary Fa’afafine voices, the work creates a dialogue between past and present, highlighting the ongoing impact of colonialism on Pacific cultures. First Impressions: Paul Gauguin – a Fa’afafine talkshow that critiques Gauguin paintings – allows for the amplification of marginalised voices, offering a platform to discuss issues of gender diversity, cultural resilience and the reclamation of agency. Talanoa between Yuki Kihara and Paul Gauguin features an imagined interview between myself and Gauguin and serves as a critical intervention, allowing me to confront and subvert his colonial gaze. This fictional interaction becomes a space to question and deconstruct the power dynamics embedded in his work, while also asserting Fa’afafine perspectives as central to the narrative. Together, these elements create a multilayered conversation that invites viewers to rethink history, representation and the complexities of identity.

A: Paradise Camp is always evolving, introducing new components at each location, from Venice to Upolu to Manchester. Why did you choose to build on the exhibition in this way?

YK: The project is inherently responsive to the contexts in which it is presented. Each location – whether Venice, Gadigal lands Sydney, Upolu, Norwich or Manchester – brings its own cultural, historical and political dynamics, which influence how the work is received and understood. By introducing new components at each site, I aim to create a dialogue between the exhibition and its audience, tailoring the narrative to reflect the specifics of each context. For example, incorporating local histories or engaging with local voices allows the work to remain relevant and impactful. This evolving approach also mirrors the fluidity of identity and the ongoing nature of decolonisation, emphasising that these conversations are not static but continually unfolding. Additionally, this method ensures that Paradise Camp remains a living, breathing thing, capable of adapting and growing as it travels, while staying rooted in its core themes of reclamation, resistance and representation.

A: How do you see the project developing in the future?

YK: Paradise Camp was created as a form of resistance, using art to assert the dignity and complexity of Fa’afafine and queer Indigenous identities. Unfortunately, the ongoing targeting of trans and non-binary people globally shows that this work is far from done. The project serves as a reminder of the resilience and strength of these communities, while also highlighting the systemic changes still needed. In the future, I see Paradise Camp continuing to evolve as a platform for advocacy and dialogue. It will adapt to the changing socio-political landscape, incorporating new voices and stories to reflect the lived realities of Fa’afafine, trans and non-binary people. The project will also expand its reach, engaging with diverse audiences and fostering solidarity across movements for gender and racial justice. Ultimately, my hope is that Paradise Camp contributes to a world where such work is no longer necessary – a world where Fa’afafine, trans and non-binary people are celebrated and protected.

A: What role does humour play in your creative practice?

YK: It plays a significant role in my creative practice, serving as both a tool for evaluation and a means of connection. In using satire, I can address serious and often painful subjects – such as colonialism, gender oppression and cultural erasure – without losing the audience’s attention or overwhelming them with heaviness. Humour creates an entry point for viewers to engage with difficult topics, encouraging them to reflect while also finding moments of joy. At the same time, this levity is deeply rooted in the resilience and creativity of Fa’afafine and queer Indigenous communities. It reflects our ability to find strength and solidarity even in the face of adversity, turning critique into a celebration of identity and survival.

A: Darwin Drag engages with research showing that Darwin changed his findings to suggest that non-heteronormative species and same-sex attraction in animals was rare. Why is this reclamation of suppressed knowledge so important right now?

YK: This work is essential because it challenges the heteronormative biases that have long shaped scientific narratives and societal norms. Charles Darwin’s framing of non-heteronormative behaviors in animals as rare was not a neutral observation, but a reflection of the conservative values of his time. This distortion of scientific understanding has had lasting consequences, reinforcing harmful stereotypes. Reclaiming this knowledge is an act of resistance. It disrupts the false narrative that queerness is “unnatural” and asserts the validity of gay existence as part of the natural world. At a time when trans and non-binary people are under attack, this is especially important, exposing how power structures – whether in science, religion or politics – have historically been used to suppress and control marginalised groups. By bringing this knowledge to light, Darwin Drag invites audiences to question whose values are upheld in the construction of knowledge and to imagine a more inclusive and truthful world.

A: What do you hope audiences take away from visiting the show at The Whitworth?

YK: An interactive aspect of Darwin in Paradise Camp at The Whitworth invites audiences to engage in a colouring exercise featuring sex-changing fish species and drag queens from the Darwin Drag video work. This interactive activity is designed to spark curiosity about the fluidity of gender and sexuality in both nature and human culture. By colouring these images, audiences are encouraged to reflect on the ways in which gender expression and identity transcend rigid binaries. The inclusion of drag queens alongside sex-changing fish challenges conventional notions of fixed identities. Through this exercise, I hope audiences take away a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of science, art and identity. I want them to see how fluidity and diversity are not only natural but also something to be celebrated. Ultimately, the program aims to foster empathy, challenge heteronormative assumptions and inspire a broader acceptance of the rich spectrum of gender and sexual expression.

Yuki Kihara: Darwin in Paradise Camp is at The Whitworth, Manchester 3 October 2025 – 1 March 2026: whitworth.manchester.ac.uk

Words: Emma Jacob & Yuki Kihara

Image Credits:

1&6. Yuki Kihara, Two Fa’afafine on the Beach (after Gauguin), 2020, c-print. Copyright: Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand.

2. Yuki Kihara, Talanoa Between Yuki Kihara and Paul Gauguin, 2022, digital video. Copyright: Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand.

3.Yuki Kihara, Nafea e te Fa’aipoipo? When Will You Marry? (after Gauguin), 2020. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand.

4. Darwin Drag, 2025, single channel video by Yuki Kihara. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand. Supported by the Sainsbury Centre, Creative New Zealand, British Council and the Whitworth, The University of Manchester.

4. Yuki Kihara, Nafea e te Fa’aipoipo? When Will You Marry? (after Gauguin), 2020. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand.

5. Yuki Kihara, Two Fa’afafine (after Gauguin) 2020, c-print. Copyright: Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand.

5. Yuki Kihara, Fonofono o le Nuanua: Patches of the Rainbow (after Gauguin), 2020, C-print. Copyright: