Between 1980 and 1990, there were only eight solo exhibitions of Black women artists in mainstream galleries. It is against this backdrop of inequality that the British Black Arts Movement emerged. Founded in 1982, the group opened up space for conversations about race and colonial legacies in the art world. Amongst them were key female pioneers, such as Lubaina Himid (b. 1954), Maud Sulter (b. 1960) and Sonia Boyce (b. 1962). Work by many of these women is on display at Somerset House, London, as part of the ground-breaking new exhibition BLACK VENUS. The show examines the historical representation and shifting legacy of Black women in visual culture. Debuted in 2022 at New York’s Fotografiska, this presentation reworks the curation with over 19 new works and six UK-based artists added to the line-up, including Boyce, Maxine Walker (b.1962) and Alberta Whittle (b.1980).

Curator Aindrea Emelife highlights the ways western societies have “othered” and fetishised Black women, whilst simultaneously challenging and reclaiming their narratives. To do so, BLACK VENUS pairs over 40 contemporary and primarily photographic artworks with a selection of archival imagery, dated between 1793 and 1930. These illustrations are a sample of historical caricatures of the Black body. They revolve around three perceived archetypes: the Hottentot Venus, the Sable Venus and the Jezebel. Through these three thematic pillars, visitors will witness the shifting image of the Black woman in visual culture. Outdated and cliched narratives are juxtaposed with complex and nuanced stories of women and non-binary artists working today. Their work offers a riotous affront to centuries-long objectification, showcasing all that Black womanhood can be, and has always been.

At the centre of the show is is the “Hottentot Venus”, a recurrent archetype appearing throughout visual culture and the epithet given to Sarah Baartman (1789-1815). Baartman was the alias imposed on a South African women, whose birth name is believed to be Ssehura. She was enslaved by Dutch colonists who then toured her as a “freak show” exhibit. The derogatory term “hottentot” refers to her heritage as part of the Khoikhoi people from South Africa, and the legacy of her treatment persisted into the 20th century. Her remains – preserved by naturalist Georges Cuvier and displayed at Paris’ Museum of Man – were only repatriated and laid to rest in Hankey, South Africa, in 2002. In this way, BLACK VENUS supplies a reminder of colonial-era exploitation and the commodification of Black bodies.

Crucially, the exhibition places such images of oppression against evocative portraits by influential Black image-makers. In HOTT-EN-TOT (1994), for example, Renee Cox (b.1960) explores the show’s titular inspiration by posing as the Hottentot Venus. Drawings of Ssehura from the time period heavily caricatured her as a sexual object to be gawked at, depicting a side or three-quarters profile which emphasised her behind. Cox rejects these representations, directing her gaze fully and unwaveringly towards the viewer, wearing metallic prosthetics that enlarge her breasts and backside. This image of the Hottentot Venus stares back; it’s a way of reclaiming agency and space. Elsewhere, Miss Thang (2009), from Cox’s psychodrama The Discreet Charm of the Bougies, places its subject amongst the trappings and luxuries of the paradigmatic housewife. Miss Thang sees the series’ fictional character, Missy, reclined and relaxed in a bubbling jacuzzi. It’s a moment of peace and rest – a Black woman experiencing self-actualisation.

BLACK VENUS looks at other archival archetypes, including painter and book illustrator Thomas Stothard’s (1755-1834) The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies (c. 1800). The image has a lot to answer for in the long-standing exoticisation of Black women in visual culture. In the etching, Black beauty is framed within the context of Western classical culture. Here, the “Sable Venus” rises from the sea on a half-shell and receives the predatory attention of the sea god, Triton. Elsewhere in the show, sexual objectification is exemplified through the Jezebel trope and the image of performer and cultural icon, Josephine Baker (1906-1975). BLACK VENUS examines Baker’s own self-awareness as a tool to challenge racial prejudice, satirising Western audiences’ colonialist sexual fantasies and narrow definitions of beauty. Baker’s approach is shared by many of the contemporary artists we meet in BLACK VENUS, who are continuing to critique harmful obsessions with Black women’s anatomy and sexuality.

One photographer doing so is Ayana V. Jackson (b. 1977). Anarcha (2017) and Black Rice (2019) offer counterimages to the cruel and dehumanising treatment of Black women between antebellum slavery and the present day. By presenting them in repose and control, the photographer subverts colonial depictions of forced labour. Jackson challenges the notion that fragility and vulnerability are attributes that belong exclusively to white women’s bodies. In conversation with Emelife, Jackson explains that: “Anarcha (2017) is based on the names of Black women who gynaecologist James Marion Sims experimented on during the slavery period in terribly brutal conditions. A lot of enslaved women had a tear between the anus and the vagina that would happen in childbirth, and Sims invented the first speculum to identify where the tear was and sew it up. Anarcha, Lucy and Betsey were [the women] experimented on the most, with up to 30 surgeries, and I wanted to honour Anarcha. I ended up thinking about historical references of the Black woman’s body at leisure, of Turkish baths, and wanted to place Anarcha in that space.”

BLACK VENUS acknowledges centuries of dehumanising representations of Black women. Against the context of such a disturbing reality, its contemporary artists shine as examples of what Black femininity can look like, and achieve. Today – unlike during the 1980s – their creative talent can be experienced in galleries across the UK. Sonia Boyce: Feeling Her Way is at the Leeds Art Gallery, and Carrie Mae Weems: Reflections for Now is at Barbican, London. As Emelife, says: “Rather than simply putting forth a compelling group of contemporary talent, BLACK VENUS defines a legacy. At a time when Black women are finally being allowed to claim agency over the way their own image is seen, it is important to track how we have reached this moment. In looking through these images, which span different stages of history, we are confronted with a mirror of the political and socio-economic understandings of Black women at the time and how the many faces of Black womanhood continue to shift in the public consciousness.”

Somerset House: BLACK VENUS: Reclaiming Black Women in Visual Culture | 20 July – 24 September

Words: Diana Bestwish Tetteh

Image Credits:

1. Ming Smith, Grace on Motor Cycle, 1978 © Courtesy of the artist and Pip py Houldsworth Gallery, London.

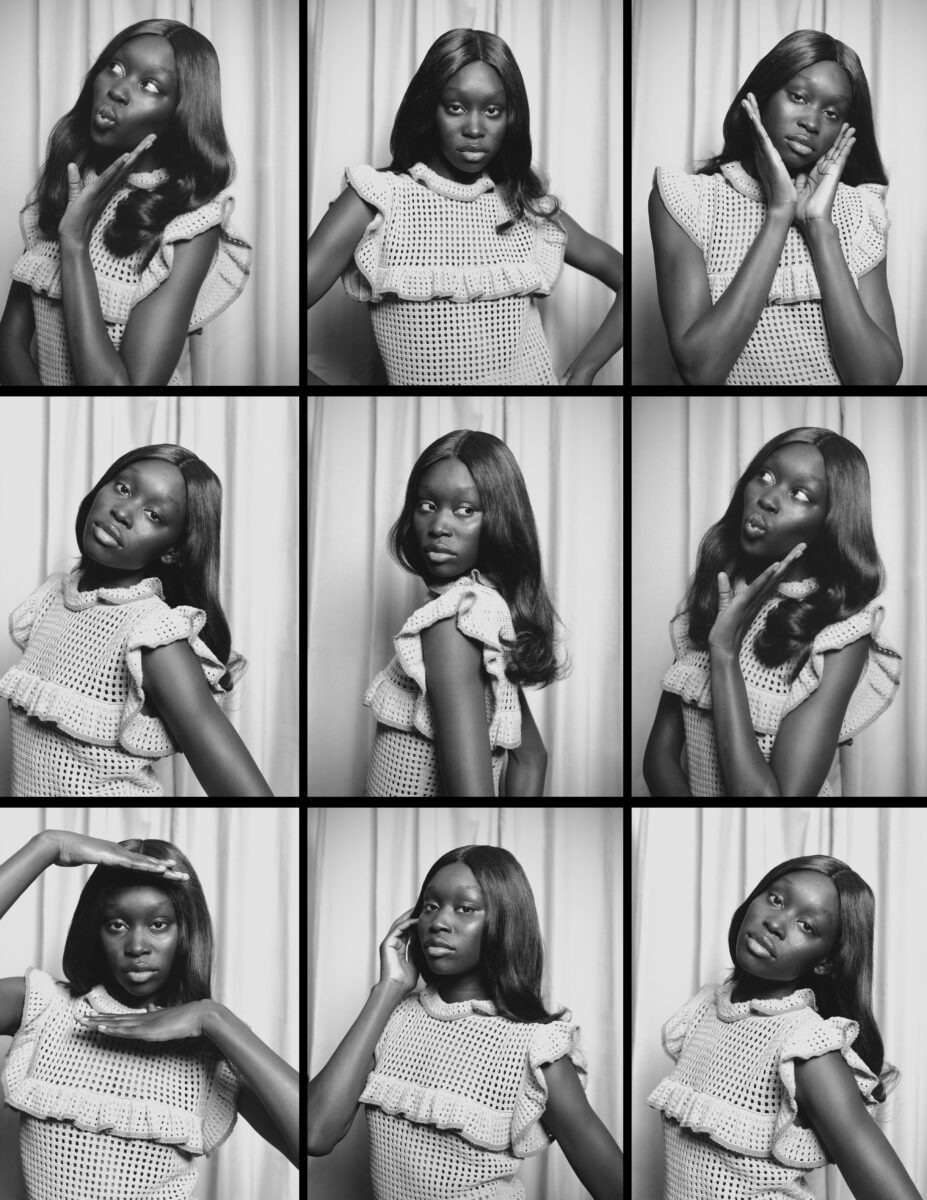

2. Amber Pinkerton Photo Booth, Sabah, Girls Next Door , 2020, © Courtesy the Artist and ALICE BLACK.

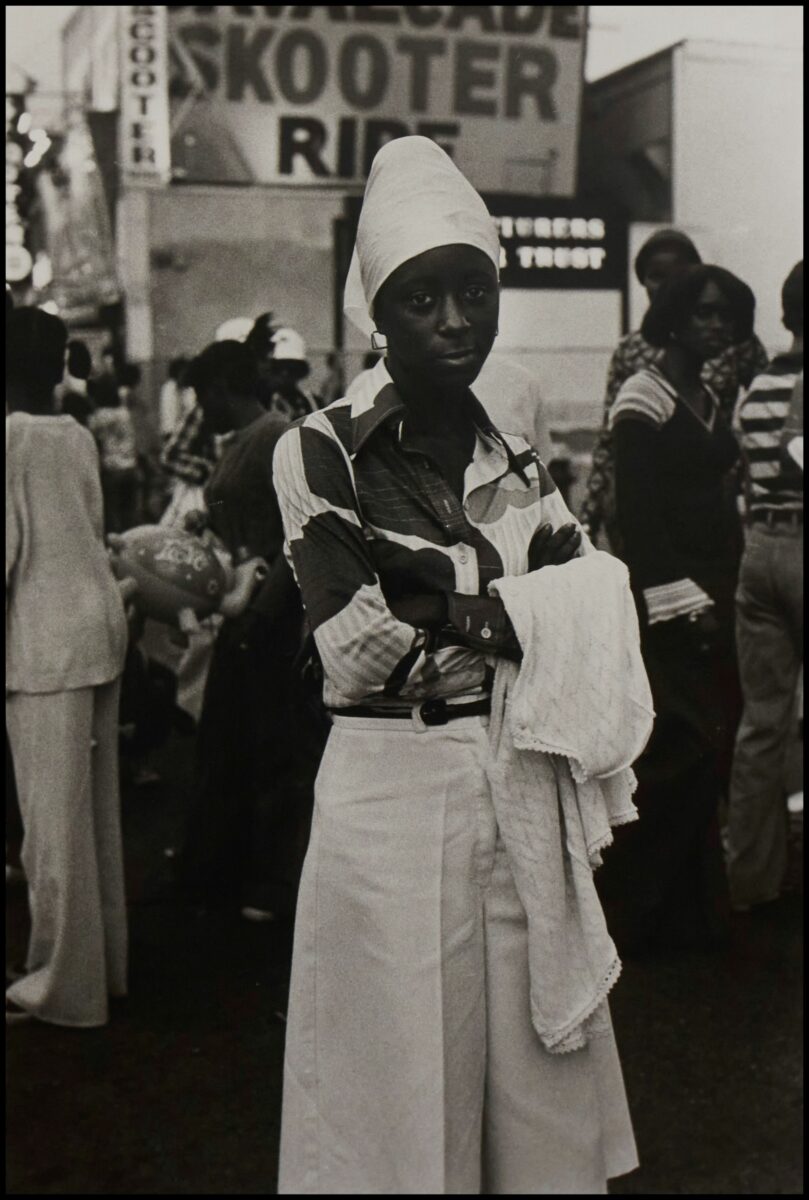

3. Ming Smith, Instant Model, 1976 © Courtesy of the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London.

4. Widline Cadet, On a Clear Day, I Thought I Saw Forever , 2020 © Courtesy of the artist.