Interview by Stephanie Bailey

When I was offered the chance to interview Matthew Higgs via The Apartment, Athens, I jumped at the chance. An artist, curator, publisher and director of White Columns, he is known for scouring antique book stores, flea markets and other places where he might come across book covers and pages including; “Art in Times of Crisis”, “Pictures in Peril”, and “Art for Spastics,” which he then frames and presents as found conceptual art. His multi-faceted practice reflects not only a world that is constantly undergoing a process of evolution, but a world in which such developments are created with pieces of the past reframed into different contexts. Such a critical approach might serve us well as we decipher events and movements in current times.

On explaining how he manages to remain so diverse in his career, he notes: “I like the spaces between these different identities/disciplines. In my own work as an artist, curator, writer, gallery director, and educator I’m interested in the points of intersection and the points of departure inherent to these disciplines. Negotiating these different roles is what I enjoy the most. In all cases it’s about making decisions and thinking about the context for the decision making process.” With a fluid and diverse approach that somewhat characterizes the inter-relationship between different disciplines within contemporary art today, and considering text is one of his main mediums, I wondered how Higgs would answer basic questions related to his own artistic practice and to ‘art’ in general via email. This is what he wrote.

Why did you become an artist?

I made a decision to go to art school around the age of 16 (I eventually went when I turned 18). I saw art – and art school – as an open territory, without an obvious outcome (or indeed any obvious employment prospects.) Unlike other options at college – e.g. law, medicine, engineering, architecture, etc. – art seemed to be, by definition, more precarious. Aged sixteen it seemed important to keep one’s options open, and art school certainly encouraged this.

Have your influences changed as your career has developed?

I became interested in art, as a teenager, through an interest in music, especially the independent music scene that emerged after punk in 1978-1981 (when I was 14-16 years old.) All my formative influences – which remain important to this day – came from music: e.g. Joy Division, Throbbing Gristle, The Fall, The Pop Group, etc. It was an exhilarating time to be growing up in the UK. The first time I saw Joy Division play live in 1979 remains the greatest thing I have ever witnessed, even as a naive fourteen year old it was clear to me that I had just experienced something of staggering significance, and that my life could never be the same again.

You are known for Imprint 93; how did you get the idea to do this, and what made you go into publishing?

I started a small publishing project in the early 1990s in London. It was a way to collaborate with artists I was interested in, and it allowed me to develop my own identity as a publisher/curator – in that Imprint 93 reflected many of the things that interested me in art at that time. I financed all of the projects myself, and they were mostly printed at night on the photocopier at the office where I worked during the day. The project was inspired by the independent publishing movements of the 60s and 70s. (“It was easy, it was cheap, go and do it!”) However in the early 1990s, and certainly in London, very few people were publishing works in this way, so Imprint 93 stood out, simply because it was fairly unique. Many of the artists who I collaborated with – including Peter Doig, Elizabeth Peyton, Jeremy Deller, Martin Creed, Chris Ofili, etc. – are now much better know, but at the time these were artists at the beginning of their careers, just as I was at the beginning of my own career as a curator. It was a very organic and mutual process.

During the 90s you promoted artists outside the YBA movement and have been known to generally shy away from the mainstream. How did you feel about the YBAs and their impact on British art? In your view, what did the YBAs (and Charles Saatchi) do for art in both general terms of the art, the artist, the audience, and the market?

I moved from the UK to the USA in 2001, so next year I will have been away for 10 years. It was clear – even as early as 1992/1993 – that the emergence and promotion of certain tendencies within British art (which would became known as the ‘YBA’) was problematic. Charles Saatchi’s support and interest in work that was visceral, theatrical, graphic, literal-minded, etc. was ultimately very one-dimensional. Paradoxically he made British art more provincial – which I’m sure wasn’t the intention. The term ‘YBA’ obviously didn’t reflect or articulate the true complexity of art being made in the UK during this period. Artists such as Tacita Dean, Steve McQueen, Peter Doig, Jeremy Deller, Liam Gillick, among many others, clearly had radically different ambitions and agendas. (It’s perhaps significant that Dean, McQueen, Doig, and others no longer choose to live in the UK.) Twenty years later the legacy of the ‘YBA’ and the British media’s ongoing obsession with its leading characters (“Damien”, “Tracey” etc.) still distorts the reception of visual culture in the UK.

What is the purpose of art today?

Art, unlike theatre, cinema, dance etc., retains a somewhat ambiguous function. I think this ‘unknown’ or ‘unknowable’ aspect of art is a significant part of its appeal. Certainly for me, growing up as a teenager in a small working class town in the North of England in the late 1970s art provided me with an opportunity to think about myself – and my life – in ways that I couldn’t have imagined otherwise.

What is an artist’s role today?

Ultimately artists – and here I include novelists, musicians, poets, playwrights, etc. – ask questions. If we look back over the history of art, it is clear that artists remain among the most perceptive commentators on the problems that we all face – as a society – at any given time.

What makes an artist?

Independent and idiosyncratic thinking and an ability to translate one’s thoughts into another medium.

What makes your work ‘art’?

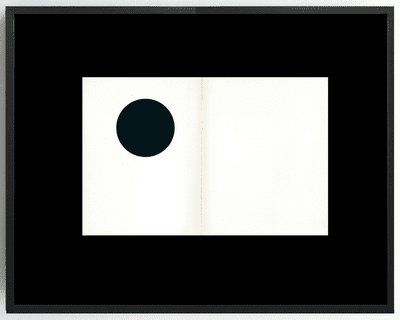

I haven’t really made a career from this kind of work; it certainly doesn’t support me financially. I’ve collected books for more than thirty years, and it’s true that my work has evolved out of this process – but I don’t think they are the same thing. My ‘art’ is simply a process of privileging something that might otherwise be overlooked or obscured. In the work I shift the context for an otherwise ordinary object – a book page, a book cover, etc. – and re-present this object within the context of ‘art’. This act alone draws attention to both the object, and my gesture, and of course it operates within a long history of artist’s working with found objects or ‘ready-mades’. I think all collectors have an interest in ‘display’ (whether they collect art, stamps, butterflies etc.), and certainly the ‘languages’ of display are crucial to my work. It’s important that my works look like art, i.e. they are conventionally framed, matted, and glazed objects. This act of ‘framing’ is significant – the works medium is described as “framed book page” – as simply framing something (e.g. a family snap shot, a poster, an award etc.) inevitably endows it with a sense of significance or purpose.

Is art important?

Art is certainly important; I believe it is vital for the ‘health’ of any culture. (We need look only to those cultures where art is suppressed to determine art’s value.) As to whether my art is important I’m not sure, and it’s also not my concern. I think my art isn’t trying to do a great deal. I’m interested in this idea, of something having quite modest ambitions, and hopefully being able to achieve them. Of course not all art operates in this way.

How do you feel about contemporary art production today?

It’s clear that the old traditional centres for art (Paris, New York etc.) no longer maintain the monopolies they ones had. Since the early 1990s we have seen the rapid de-centralization of the art world, and the emergence of communities of artists working internationally and across borders. This has created a much more complex ‘map’, a constantly shifting geography for art and artists – which remains in flux. Technology has accelerated and amplified these conversations, which in turn creates a new kind of accessibility for art and ideas – which is unprecedented. I think it’s too early to say what these changes mean, but its clear that things won’t be the same again, which is as it should be.

Image © the artist and courtesy the gallery.