In a 1944 lecture, Estonian-born American architect Louis Kahn (1901-1974) described “monumentality” as “a spiritual quality inherent in a structure which conveys the feeling of its eternity, that it cannot be added to or changed.” Whilst the scale and heft of his buildings is often associated with Brutalism, this quote gestures towards a more humanist and spiritual approach – one which places him in the company of the world’s most important architects. A new book from Prestel, The Essential Louis Kahn, uses Turkish photographer Cemal Emden’s beautiful, light-filled images to accompany a meditation on Kahn’s practice.

Introduced by critic Jale N. Erzen, with commentaries by design historian Caroline Maniaque and a chronology by Ayşe Zekiye Abali, the title offers a linear survey of 23 iconic projects – from the modest simplicity of his Trenton Bath House in New Jersey (1954-1959) to the vast grandeur of the Sher-e-Bangla Nagar parliamentary complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh (started in 1962 but only completed after Kahn’s death, in 1983). Erzen’s text explores some of the motifs by which Kahn sought to embody the condition of monumentality. Sometimes seen as the Frank Lloyd Wright of modernist architecture’s second great wave (the first having occurred during Wright’s heyday, the 1910s-1930s), Kahn’s great contribution to Western modernism was to develop the idea of space or void.

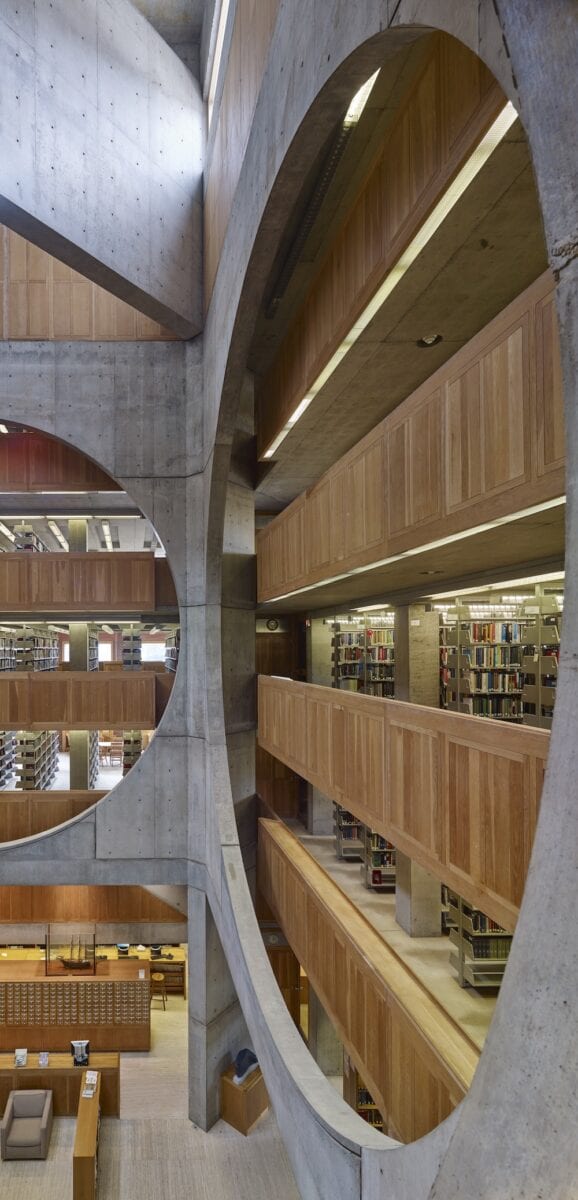

The most obvious manifestation of this was in the enormous cut-out shapes – often segmented circles – which punctuate many of his external elevations. They create a cross-section effect, as if the eye were penetrating sideways through the structure. The motif is evident in Kahn’s designs for the Performing Arts Theatre at Fort Wayne, Indiana, reaching its zenith with the wonderful, stark abstraction of the Indian Institute of Management at Ahmedabad (1962-74) and the Sher-e-Bangla Nagar site.

Many of the featured builds incorporate gaps between walls, ceilings and other structural elements – such as the so-called “floating roof” of the Trenton Bath House. His buildings often seem composed of free-floating elements, in spite of their enormous size. One striking extrapolation of this idea was to use layered or nested walls to create antechamber-type spaces, combining the ambience of interior and exterior. The technique was established for the First Unitarian Church of Rochester, New York (1959-1962, 1965-1969), in which an outer layer of classrooms encloses a central space for worship surrounded by an unbroken wall and corridor. Again, the concept was consolidated at Dhaka, where, in Maniaque’s words: “an interior ‘street’ is created between the chamber in the centre and the offices located on the perimeter.” Kahn’s corridor-based classrooms at the Indian Institute of Management and the internal “courtyards” of his Yale Centre for British Art (1969-77) activate this same sense of outside-inside space.

Connected to Kahn’s fascination with empty spaces was a concern with light as a means of creating or enhancing the quality of openness. Often, he worked with ceiling light-sources to produce a more seamless or meditative visual effect. Distinctive, waffle-shaped or hollow triangular ceiling panels feature in many of his structures, notably the Yale University Art Gallery (1951-1953) and Centre for British Art, and his dormer complex at Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania (1960-1965). The individual units with which Kahn created his ceilings generally included glazed surfaces to allow light through, whilst the internal support they offered removed the need for columns or arches – allowing for more expansive interiors.

Kahn worked with a basic set of shapes that, whilst connected the minimalism of the Modernist era, were also rooted in his studies of Renaissance forms and ancient religious structures. The prism, square and circle were of particular importance, and seemed to bring him closest to the embodiment of timeless human values. He wrote and talked about architecture as an elementary expression of human consciousness; the shapes he used frequently had iconographic qualities, such as the Greek cross layout of the Trenton Bathhouse, and the multi-faith connotations of his circular openings.

At the same time, Kahn was a committed modernist in his belief that form should express function: from the horizontal ridges on the external walls of Yale Art Gallery, marking out internal floor levels, to the use of brick and concrete to distinguish between load-bearing and non-load-bearing elements in the Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research Laboratory (1957-1960).

The Essential Louis Kahn is published by Prestel. Find out more here.

Words: Greg Thomas

Image Credits:

1. Sher e Bangla Nagar, Capital of Bangladesh © Cemal Emden, ‘The Essential Louis Kahn’ (Prestel, 2021)

2. Kimbell Art Museum © Cemal Emden, ‘The Essential Louis Kahn’ (Prestel, 2021)

3. Exeter Library © Cemal Emden, ‘The Essential Louis Kahn’ (Prestel, 2021)

4. Fine Arts Centre, School and Performing Arts Theatre © Cemal Emden, ‘The Essential Louis Kahn’ (Prestel, 2021)

5. Sher e Bangla Nagar, Capital of Bangladesh © Cemal Emden, ‘The Essential Louis Kahn’ (Prestel, 2021)

6. Ayup National Hospital © Cemal Emden, ‘The Essential Louis Kahn’ (Prestel, 2021)