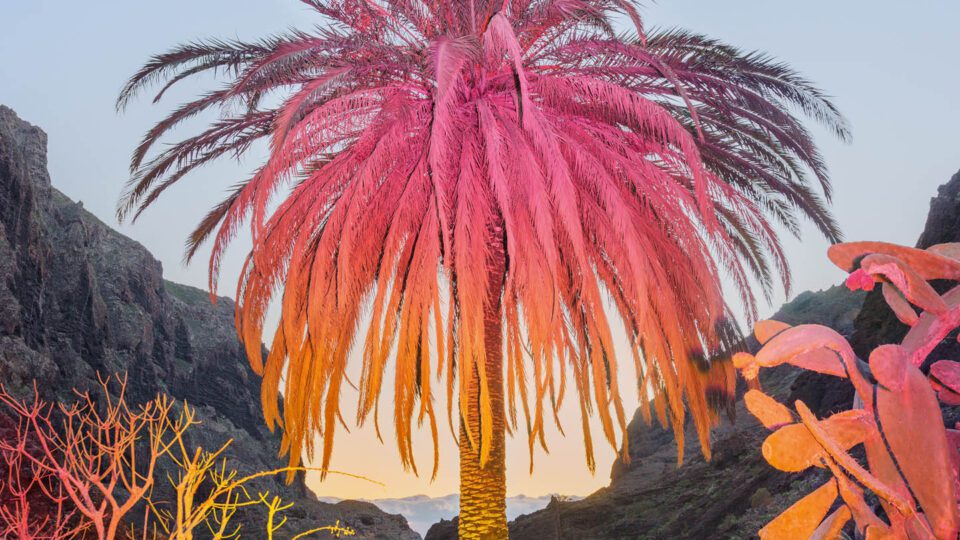

“It’s good to screw around and mess with photography – it needs to be done,” says Inka & Niclas Lindergård, the Stock- holm-based artist duo who has worked together since 2007. There’s perhaps no better example than Adaptive Colorations I, a photo-sculpture in which a craggy mountain ridge peeks out from the opening of a cave, glowing turmeric yellow and neon pink. The image is screen printed onto a three-dimensional block of wood, offering different vantage points. Here, dreamlike photography is rendered into a tangible 3D object.

This innovative artwork, part of “a series of sculptures created by floating a photograph on the surface of the water and dipping a shape into it”, is on display in Second Nature: Photography in the Age of the Anthropocene at the Cantor Arts Center in Stanford University. The show is several years in the making, and is accompanied by an expansive photobook published by Rizzoli. It considers the age of human domination over planet Earth through the lens of 44 creatives, tying together urban crisis with disappearing natural abundance.

“There was the humanity component – the ‘anthropos’ part – and there was also the physical transformation of the environment to consider,” says Jessica May, the Executive Di- rector of the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art and a Co-Curator. “At the same time, we were starting to see the Anthropocene enter public discourse, and a transformation of photography itself. So many photographers are really pushing the medium in different ways, and that is a function of the emergence and dominance of digital practices post-2000.” Inka & Niclas, with their hyperreal multidisciplinary style, are part of this shift. They are interested in “the visual mechanics of nature photographs,” and have been included in a number of similarly-themed shows, from Human / Nature at Fotografiska New York to, more recently, Apocalypse: From Last Judgement to Climate Threat at Gothenburg Museum of Art.

May co-curated Second Nature with Marshall N. Price, the Chief Curator at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, where the exhibition first launched. They pored over thousands of artworks before settling on 63 to exhibit. Price recalls: “We wanted the artists in the show to reflect the globality of the conundrum, and so that informed the process.” The photographs traverse continents and biomes, cities, forests, and oceans, exposing humans’ paradoxically outsized scale to the majestic geology of the planet. Even though, physically, humans are tiny in front of nature, the rapid as- cension of technology, the 4.06 trillion dollar global real estate market, and the overpopulation of cities has irrevocably transformed the planet with carbon dioxide emissions, fossil fuel use, erosion of natural habitats and deforestation.

“I knew before this project that the Earth was four-and-a-half billion years old, and humanity has only been here for a very short period of time,” Price explains. “When you zoom out and think about time on a geological scale, you realise how impactful humanity has been on the globe. And just thinking about that puts urgency of the moment in to relief.” The show and book are divided into four categories: the reconfigura- tion of nature thanks to the meteoric increase in human activ- ity across the past couple of centuries; the notion of the “toxic sublime” – or finding otherworldly beauty in the banality of excess pollution and environmental destruction; and the disjointed geographies resulting from profit-driven capitalist development and resource extraction. It concludes with the “new reality” that the Anthropocene has imposed on human- ity, and which humankind has likewise enacted on the Earth.

Coined by biologist Eugene Stoermer in the 1980s, and then developed by scientist Paul Crutzen at the dawn of the millennium, the Anthropocene is a proposed unit of geologic time in which humans have irreversibly impacted the Earth’s climate and ecosystems, causing glaciers to melt and erod- ing the atmosphere with toxic gas emissions. “It’s a pity we’re still officially living in an age called the Holocene,” Crutzen wrote for the Yale Environment 360 in 2011. “The Anthropo- cene – human dominance of biological, chemical and geo- logical processes on Earth – is already an undeniable reality.”

Nature and landscape have a vaunted place in the history of photography, epitomised by Ansel Adams’ striking mono- chrome portraits of America’s wilderness, which helped pave the way for environmental conservation and the creation of national parks. Eliot Porter’s close ups of birds in vivid col- ours, and the symmetric congruence of trees, contended with the quiet solitude of nature, before it was significantly dis- turbed by human intervention. Even Henri Cartier-Bresson, widely known for his surrealist shots of cities, practiced his trademark geometric composition in landscape photographs.

Today, in the age of Instagram, travel pictures appear on social media for the sake of mass consumption and perfor- mance. The idealisation of nature spots and seemingly un- touched views spur collective interest and tourism, not unlike Adams and other early nature photographers’ endeavours to lobby visitor interest and investment in the American West. This is where Inka & Niclas enter the conversation. Their work is underpinned by the same phenomenon: the satura- tion of landscape imagery in public imagination. “There are so many complex dynamics at play between humans and nature. We travel, we photograph, we consume, using images of nature to shape our identities now more than ever before.”

Nature is a wellspring of inspiration for the duo, an almost magical utopia of rocks, caves, mountains and beaches per- vaded by their hallmark technique of capturing and manipu- lating light in fluorescent colours. They revel in being out- doors – in “feeling the wind in your face, feeling small.” Most of all, they want people to consider places from a different viewpoint. “All of our work, in one way or another, deals with perception. Much of it starts with how we, as humans, per- ceive and consume nature. It’s a visual medium, and we try to provoke the eye. If we can give you all the clues, lay every- thing out in front of you clearly, and still make you question what you’re looking at, then we’ve succeeded in some way.”

At Cantor, Adaptive Colorations functions as a metaphor for this: “There’s something poetic about being able to dip objects into photographs. The image warps, stretches, and eventually breaks apart. What’s left is something perfectly sharp, vivid, and readable – yet cryptic and strange.” Like- wise, the duo’s wider body of pictures doesn’t always seem real. Instead, they feel like illusory portals to an immersive, almost otherworldly unknown. In The Belt of Venus and the Shadow of the Earth (2013), a seaside boulder radiates a deep blue glow, darker than the azure sea or the cerulean sky in the background. In another shot, a serrated rock emits a yellow-orange light, and the centre of it beams a translu- cent pink. Inka & Niclas trigger fantasy and wonder, the same impetus that led humans thousands of years ago to inventmyths about the beauty and brutality of the sea, sky, woods and mountains. “Hopefully, we’ve transported you to a place where the lines are a bit more blurred – because lines need to be more blurred for everyone to reflect,” the duo explains.

And there is a lot to think about. The onset of the Anthropo- cene dates to the rise of industrial capitalism, and the system- ic colonisation of lands across the Americas, Asia, Africa and Australia. The exploitation, enslavement and / or genocide of Indigenous peoples incurred a loss in collective practices that protected places communities had called home for gen- erations. Second Nature responds to these issues. In Camille Seaman’s 2016 shot, Iceberg in Blood Red Sea, a snow white iceberg floats in Antarctica on a red ocean translucent with shards of fragmented ice, showing how melting icecaps are escalating the slow but gradual uninhabitability of the planet. The iceberg may appear almost beautiful in its fissure, but on the opposite yet parallel end of the earth in the Arctic, Inuits’ way of life is threatened. Sheila Watt-Cloutier, an Inuk activist, writes in the book: “[T]he snow and ice coverings over which we access our traditional foods are becoming more and more unreliable and therefore unsafe, leaving our hunt- ers more prone than ever to breaking through unexpectedly thin ice or being swept out to sea when the floe-ice platform, on which they are hunting, breaks off from the land-fast ice.”

Similarly, an untitled piece from Sammy Baloji’s photo montage series Mémoire superimposes black-and-white cut-outs of Congolese men from colonial times on con- temporary colourised landscapes of capitalist progress and construction. The spectral presence of people who toiled for Belgium’s extraction of ivory and rubber from the Congo is effectively linked with today’s industrial development, the past rehashed via multinational corporations, sweatshop fac- tories or staggeringly unequal housing schemes, at the ex- pense of labourers rendered invisible by mainstream history.

Meanwhile, the bustling hub of the city collides with the brute force of nature in Anastasia Samoylova’s Pink Sidewalk, part of FloodZone (2017), made in Miami in the wake of Hurri- cane Irma. The pictures use pastel palettes – creating a visual synergy with Inka & Niclas – to expose the anxiety confront- ed by coastal locales that find their way of life threatened by rising sea levels. Meanwhile, Pablo López Luz’s Aerial View of Mexico City reveals how human-made places are, at this point, more common than untouched terrains – like those shown by the duo in series The Belt of Venus or 4K Ultra HD (2018).

Even urban areas, with concrete towers and smart plan- ning, are at risk of natural disaster. The 2023 Turkey-Syria earthquake claimed over 55,000 lives, and most recently, the wildfires wreaked destruction in Los Angeles, the second- largest city in the USA. Laura McPhee’s Late Summer (Drifting Fireweed) shows an arid forest in LA after a wildfire, the light of dawn slanting through barren trees. Whilst the photograph is almost 20 years old, it remains as timeless as ever: the veloc- ity of the Santa Ana winds spur wildfires as an inevitability in southern California, which is only further aggravated by LA’s carbon emissions, 19 per cent of which arise from traffic. “We started working on this exhibition in 2016, almost a decade ago.At that time,the world was in a different place in terms of what we expected climate change to bring,” May reflects. “We’re looking at a dramatically changing planet. The show reminds me that there’s a lot of different futures for humanity. How we choose to move forward will mean the difference between survival and extinction. It feels very stark.”

Image credits:

1. Inka & Niclas, 4K Ultra HD II (TROPICAL), (2018). Image courtesy the artists, Dorothée Nilsson Gallery and Bildhalle.

2. Inka & Niclas, 4K Ultra HD IX, (2018). Image courtesy the artists, Dorothée Nilsson Gallery and Bildhalle.

3. Inka & Niclas, The Belt of Venus and the Shadow of the Earth I, (2013). Image courtesy the artists, Dorothée Nilsson Gallery and Bildhalle.

4. Inka & Niclas, The Belt of Venus and the Shadow of the Earth IV, (2013). Image courtesy the artists, Dorothée Nilsson Gallery and Bildhalle.

5. Inka & Niclas, The Belt of Venus and the Shadow of the Earth V, (2013). Image courtesy the artists, Dorothée Nilsson Gallery and Bildhalle.