Just three percent of the world’s land remains ecologically intact, with healthy numbers of all its original animals and undisturbed habitat. According to WWF’s Living Planet Report, the average size of wildlife populations fell by a staggering 73% between 1970 and 2020, and a 2022 study warned that more than 1 in 10 species could be lost by the end of the century. A new book from Zed Nelson asks the question: how did we let ourselves get here? The Anthropocene Illusion is the result of six years of travel, during which the photographer visited 14 countries across four continents to observe how humans immerse themselves in increasingly artificial landscapes. People holiday on synthetic beaches and ski on false snow, observe endangered animals in zoos and aquariums, or else take part in luxury experiences that encroach upon ecosystems and habitats. Each page is a new jarring angle on the same problem, driving home one message: humanity clamours to be closer to real, authentic nature, and yet our destructive behaviours systematically and irreversibly erode these spaces. The story of human folly in the face of climate disaster has been told before – in fact, there is so much environmental reportage that “climate fatigue” has become an increasingly hot topic – but few tell it better than Nelson.

The photographer has a reputation for looking society’s most pressing issues in the eye. His seminal project, Gun Nation, is a disturbing reflection on America’s deadly love affair with the weapon. The compelling images explore the paradox of why America’s most potent symbol of freedom is also one of its greatest killers – resulting in an annual death toll of over 30,000 citizens. It is widely considered to be one of the definitive bodies of work on the topic, and won the Alfred Eisenstaedt Award, First Prize in World Press Photo Competition and the Visa d’Or. Subsequent works include Love Me, which explores the insidious power of the beauty industry, and In This Land, which reflects on the mindset of contemporary Israel. The Anthropocene Illusion, meanwhile, has already seen Nelson named Sony World Photographer of the Year, and is sure to garner more acclaim in the months to come. Clearly, the fact that Nelson cut his artistic teeth on some of the most divisive topics in contemporary life has stood him in good stead for this latest project. The book begins with a scathing indictment of modern life: “humans have left the countryside for the city. We have separated ourselves from the land we once roamed, and from other animals. But somewhere deep within us the desire for contact with nature remains. So, while we destroy the natural world around us, we have become masters of a stage-managed, artificial ‘experience’ of nature, a reassuring spectacle, an illusion.” The introduction sets the tone for the rest of the volume, taking readers into a world of farcical holiday experiences and pitiful imitations of wildlife.

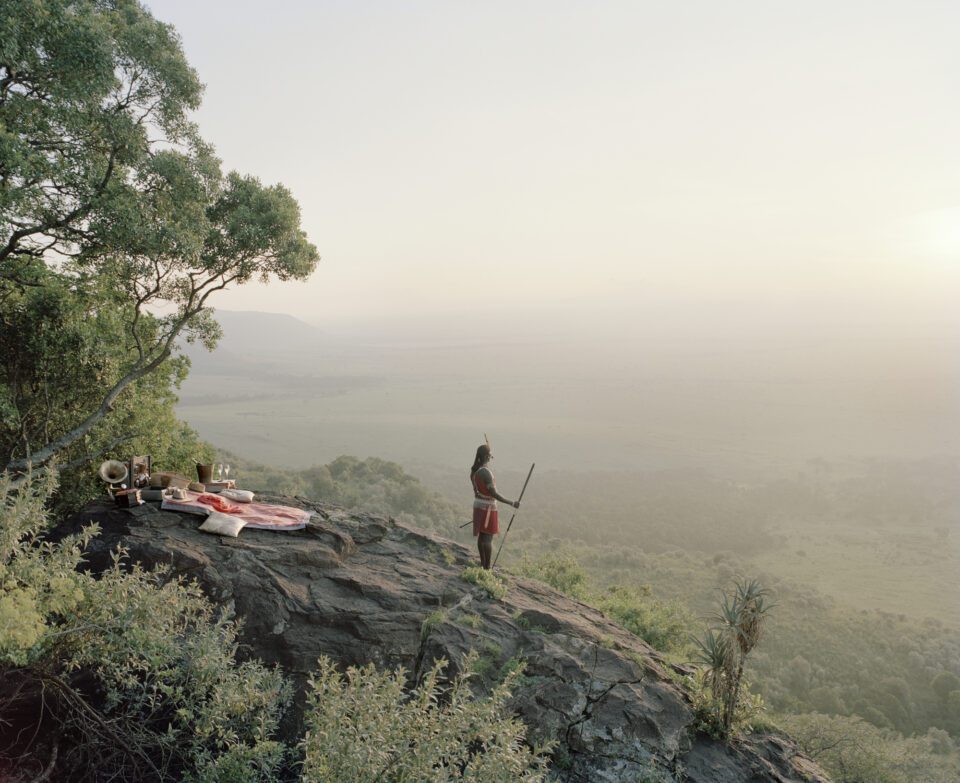

Humanity’s desire to replicate the natural world is palpable throughout The Anthropocene Illusion. The result of this endeavour borders on the uncanny. This is the organic world, but not as it should be. Something feels wrong – mountains are oddly flat, and ski slopes covered in false snow. One image of a huge tree at Taiyuan Zoo in China is particularly disquieting. It is adorned with orange leaves and looks ancient, gnarled and weathered. Only a closer look at the caption reveals that the tree is made from polyurethane, concrete and acrylic. Elsewhere, several pages are dedicated to a Tropical Island holiday resort. The twist? This “exotic” location is a short train ride from Berlin. Housed inside a 107-metre-high dome – making it taller than the Empire State Building – the holiday destination has a sandy beach, a butterfly house and the world’s largest 10,000 square metre indoor rainforest. There is also a waterfall and a mangrove swamp with live turtles, dragonfish, flamingos and macaws. Nelson uses the camera to systematically tear down the notion that these experiences are anything close to the real thing. The artist writes: “In the numerous theme parks and zoos I visited, I realised a strange thing … In these manufactured landscapes, with smooth tarmac walkways, piped music, filtered air and corralled animals, nothing happens unless it’s part of the show. Here nature is made safe – no thorns, biting insects, flooding or unpredictable creatures. This is nature only as spectacle.”

The most gut-wrenching of Nelson’s images are, without question, those of animals. In one arresting shot, a polar bear is held in captivity in Dalian Forest Zoo, China. It appears to be indoors, sitting on a block that has been made to look like an iceberg. Its attention is turned to the wall, which has been painted as an arctic tundra. It is a pitiful replica of the real frozen landscape, made all the shoddier when compared with the majesty of the bear. Similar stories are told at the Bronx Zoo and Shanghai Wild Animal Park, where monkeys perch before a painted jungle façade. Here, Nelson broaches a topic that has been controversial for generations: are zoos ethical? Many of these institutions cite conservation, the breeding and monitoring of endangered species and scientific research as reasons for their continued existence, yet zoos that are exploitative, poorly run and prioritise profit over welfare continue to exist. Regardless of the wider debate, the real tragedy is that many species exist solely in captivity, or at least, are more common in zoos than in the wild. Nelson quotes critic and writer John Berger, who captures in words what Nelson does in photographs: “Everywhere animals disappear. In zoos they constitute the living monument to their own disappearance.” Even pictures taken outside of the zoo setting are alarming. The image Walk with Lions Tourist Experience, South Africa is a prime example. Two lions crouch before a gamekeeper, drinking out of puddles on the path. Their positioning and behaviour would be more fitting to domestic cats and there is no escaping the feeling that humanity has diminished these impressive creatures.

The Anthropocene Illusion is a triumph. The book takes one of the biggest topics in modern discourse and distils it down to single moments, driving home a message that is often too big to comprehend. Nelson uses experiences that many take for granted – holiday parks, zoos, reserves – to remind readers of their absurdity. It is a wakeup call, holding each person accountable for their disconnect with nature. The dire situation is laid bare, but it is only through looking directly at where humanity has gone wrong, that we can begin to set things on the right path.

The Anthropocene Illusion by Zed Nelson is published by Guest Editions: guesteditions.com

Words: Emma Jacob

Image credits:

1. Snow cannon producing artificial snow. Dolomites ski resort. Italy © Zed Nelson / Institute.

2. Out of Africa champagne picnic experience. Masai Mara luxury safari. Kenya © Zed Nelson /

Institute.

3. Carpark. Park Royal Pickering hotel, Singapore. © Zed Nelson / Institute.