Harold “Doc” Edgerton (1903-1990), was a pioneer of high-speed imaging who made it possible to see what the human eye cannot. Frequently cited as “the man who froze time,” the MIT professor of electrical engineering transformed an obscure laboratory instrument – the stroboscope – into powerful flash systems, laying the groundwork for the kind of flash technology found in cameras today. MIT Museum’s aptly-named Freezing Time is, according to Director Michael John Gorman, “the first exhibition to really interrogate Edgerton’s experimental journey in developing his innovative image-making processes.” The display mines the museum’s vast holdings to foreground the apparatus and experiments that underpinned Edgerton’s better-known pictures, as well as showcasing “once famous but forgotten photographs.”

Edgerton learned that an intense flash of light could make a moving machine appear still whilst studying as a graduate student at MIT during the late 1920s. Deborah G. Douglas, Senior Director of Collections and Curator of Science and Technology at MIT Museum, explains: “It all started because he was fascinated but frustrated by a French instrument, the Stroborama, that didn’t allow him to take pictures of the electric generators he was studying.” In 1932, he iterated on these studies through his doctoral dissertation, using a stroboscope – invented in the 1830s – to take a photo of a motor in motion. This was a turning point. He, and later his students, turned this earlier technology into high-intensity flash systems capable of producing exposures at previously unimaginable speeds. Visitors to MIT will come face-to-face with such devices, including the General Radio “Edgerton Stroboscope” and Kodatron Speedlamp. The latter provided short, powerful bursts of light and was advertised with the strapline: “no human motion is too fast for this lamp.”

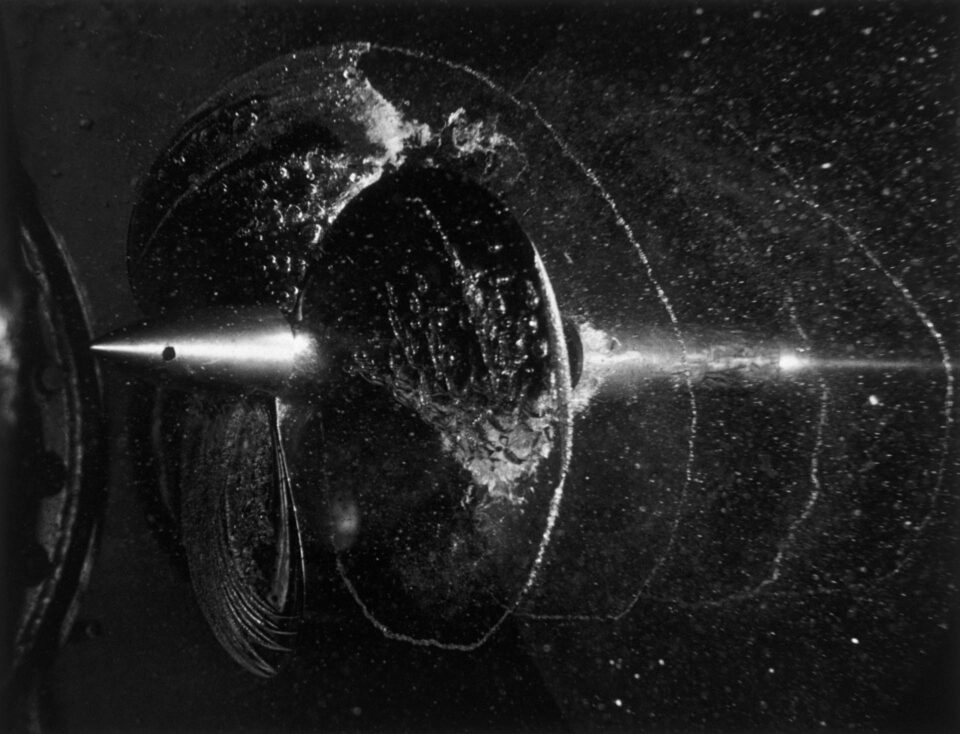

In 1932, Edgerton captured his first “art image”: a high-contrast photograph of water flowing from a tap. He continued this practice for decades, immortalising moments like a golfer’s swing or a milk drop hitting a table. By 1937, one of Edgerton’s milk-drop photographs, titled Coronet, had been included in the Museum of Modern Art’s first photography exhibition, cementing Edgerton as an influential figure in the medium. It’s an instantly recognisable composition, and a later colour version from 1957 is listed as one of TIME’s 100 Most Influential Images of All Time. Another of Edgerton’s most famous pictures captures an apple being pierced by a .30 caliber bullet. Freezing Times gives deeper insight into these iconic shots.

Despite being featured in one of the world’s leading art museums, Edgerton always insisted he was a scientist, famously stating: “Don’t make me out to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts. Only the facts.” Yet the visual impact of his work is undeniable. Douglas adds: “We might never have known about Edgerton if he hadn’t applied that technology to taking incredibly beautiful and intriguing photographs, that seemed to freeze time itself. By combining theory, experiment, and artistry, Edgerton gave us tools and techniques to freeze time and help us better comprehend our world.”

MIT Museum’s show highlights the wide-reaching nature of Edgerton’s groundbreaking technological advancements. As Douglas notes: “Edgerton’s efforts, along with those of his students, to radically improve that technology had an immediate impact on industry … Every day, we benefit from the technical innovations made by Edgerton – from the flash on a camera to the beacon that warns an airplane of a high hazard.” He had an impact on everything from the film industry (Quicker ‘n a Wink, a documentary about his work, won an Oscar in 1940), to accomplishments in sports photography, sonar and military surveillance. Freezing Time is testament not only to a beloved professor and extraordinary researcher, but also to what can happen when art and science collide – giving life to something entirely new.

Freezing Time: Edgerton and the Beauty of the Machine Age

MIT Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, until 8 October.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits: Harold Edgerton, photographer, © MIT, Courtesy MIT Museum. Used with permission.