The story begins, as so many do in the history of modern photography, with an image: a woman behind the camera, calibrating light, waiting for a moment to materialise, composing an understanding of the world. Women Photographers 1900-1975: A Legacy of Light, which recently opened at NGV International, expands this gesture into a sweeping, multi-generational portrait of creative ingenuity. More than 300 works by over 70 artists illuminate the breadth and complexity of women’s contributions to photography during one of the most turbulent and transformative eras in modern history. The exhibition begins with a single idea – that women’s perspectives shaped photography – and transforms it into a global narrative.

From the outset, the exhibition revels in plurality. It brings together portraiture, photojournalism, landscape, fashion, experimental modernism and intimate studies of the everyday, all held within the same frame of inquiry. These images are not footnotes to a male-authored story but pioneering works born from the social, political and cultural currents of their times. The span from 1900 to 1975 encompasses suffrage movements, global conflicts, mass migration, shifting labour patterns, decolonisation and the energy of second-wave feminism. Against this backdrop, the featured artists forged new modes of seeing.

Diane Arbus’s disquieting portraits sit in conversation with Dora Maar’s surrealist interventions, offering two radically different ways of approaching the human subject. Arbus insists on presence, on the unvarnished textures of life lived at the periphery, whereas Maar uses the photograph as a stage for psychological tension. Yet both destabilise the notion of a singular gaze. They remind us that photography is always a negotiation between maker, subject and viewer. Lee Miller provides another axis in this constellation – a figure who crossed boundaries both artistic and geographic. From the fashion studios of New York to the boulevards of Paris and the devastation of wartime Europe, Miller’s lens is dynamic and adaptive. Her 1931 portrait of Man Ray arrests the viewer with tight framing and a diverted gaze. Rather than solidifying the myth of the male artistic genius, the image positions Miller as the one in control.

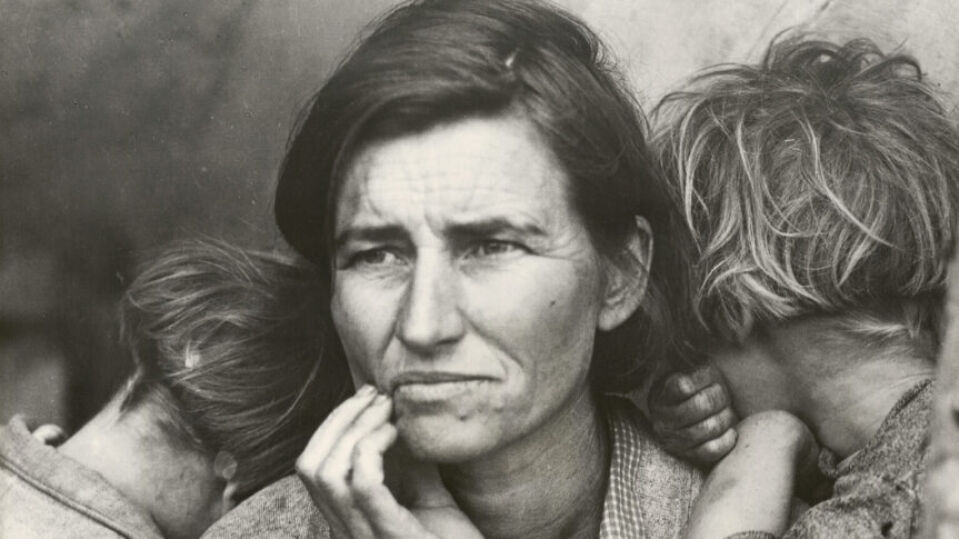

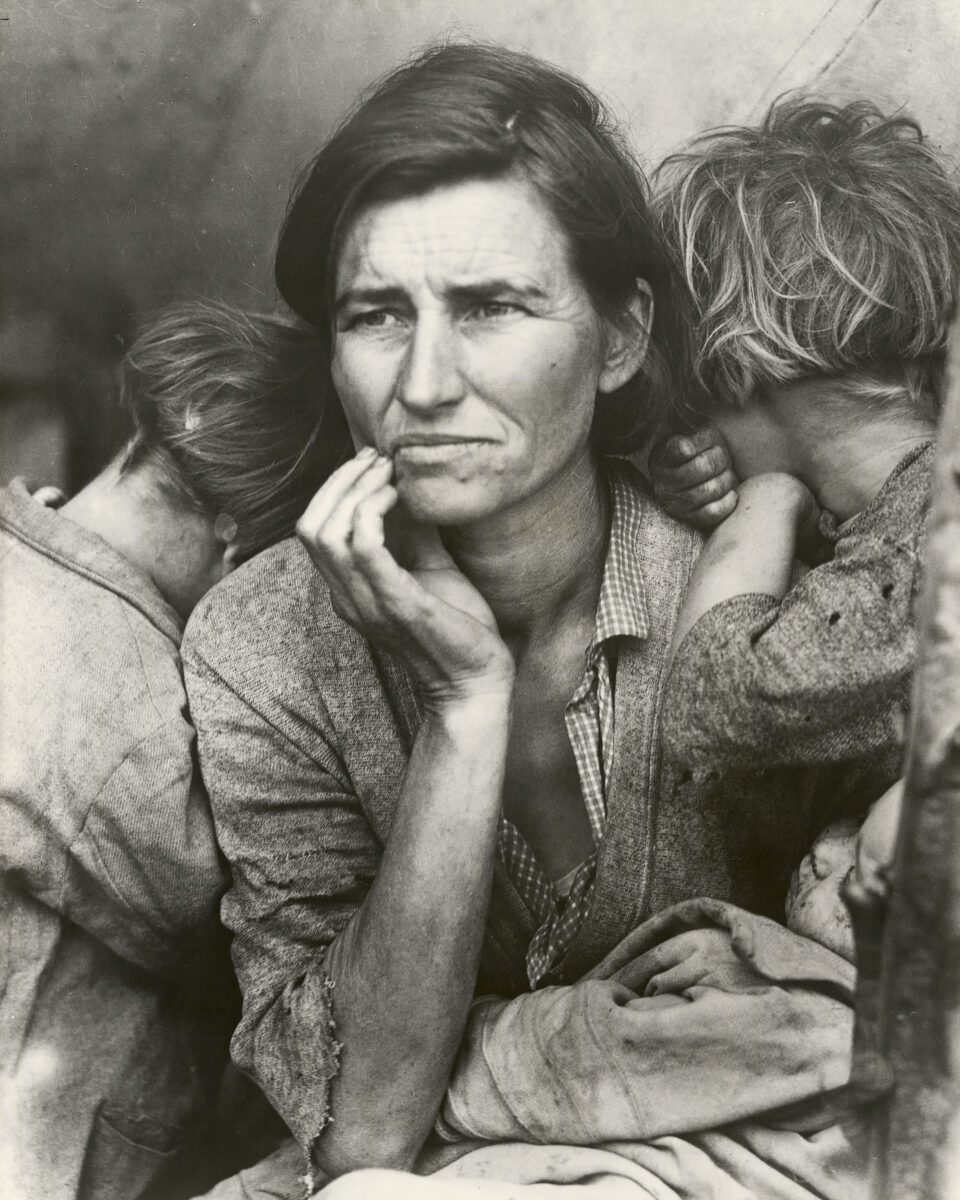

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother functions almost as a gravitational centre within the exhibition. Seen countless times in textbooks, the image’s presence is renewed, contextualised within Lange’s wider commitment to human dignity during the Great Depression. She photographed Florence Owens Thompson and her children not to cement an icon but to bear witness to a national crisis. It is the difference between exploitation and empathy, between mythmaking and advocacy. Lange’s work reveals photography as a tool for social consciousness – a thread running through many practices in the exhibition.

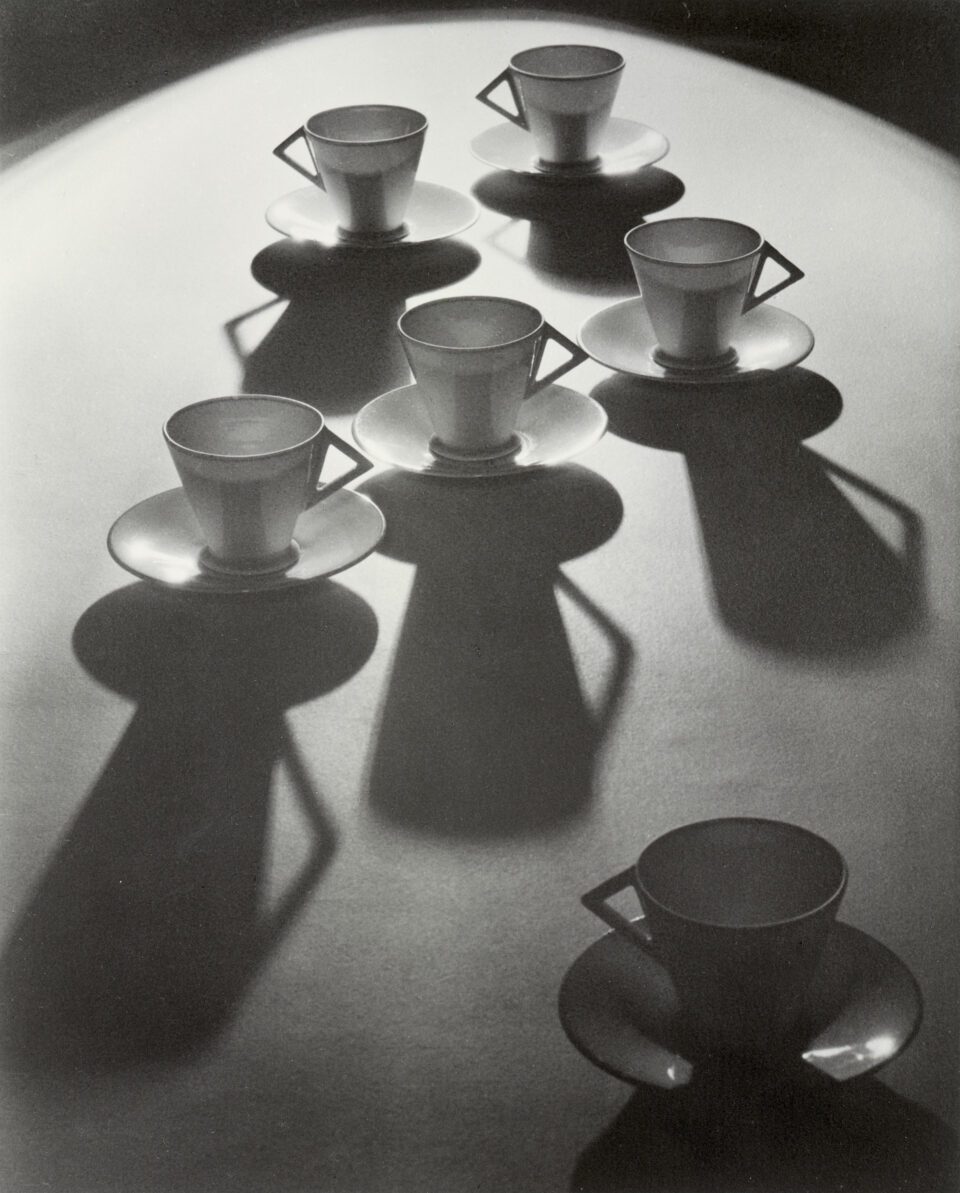

The brilliance of A Legacy of Light lies in how it highlights artists long overshadowed. Lola Álvarez Bravo’s Las Lavanderas transforms women washing clothes into a dynamic composition of shadow and rhythm. Her sensitivity to light and movement is matched by a deep respect for her subjects. Meanwhile, Olive Cotton redefines domestic space through abstraction. Her Teacup Ballet from 1935 converts crockery into a choreography of light and shadow, rendering the mundane sublime. Though Cotton’s work is formally distinct from Bravo’s, both elevate the often-unseen lives of women into poetic resonance.

Ilse Bing’s explorations of the self add another dimension. Her Self-portrait of 1931 – a modernist tangle of mirrors, angles and reflection – shows how the camera can reveal and distort identity. There is a quiet humour in the image, as Bing juxtaposes her face with the omnipresent eye of the Leica. It is a reminder that women photographers have long interrogated the mechanics of looking.

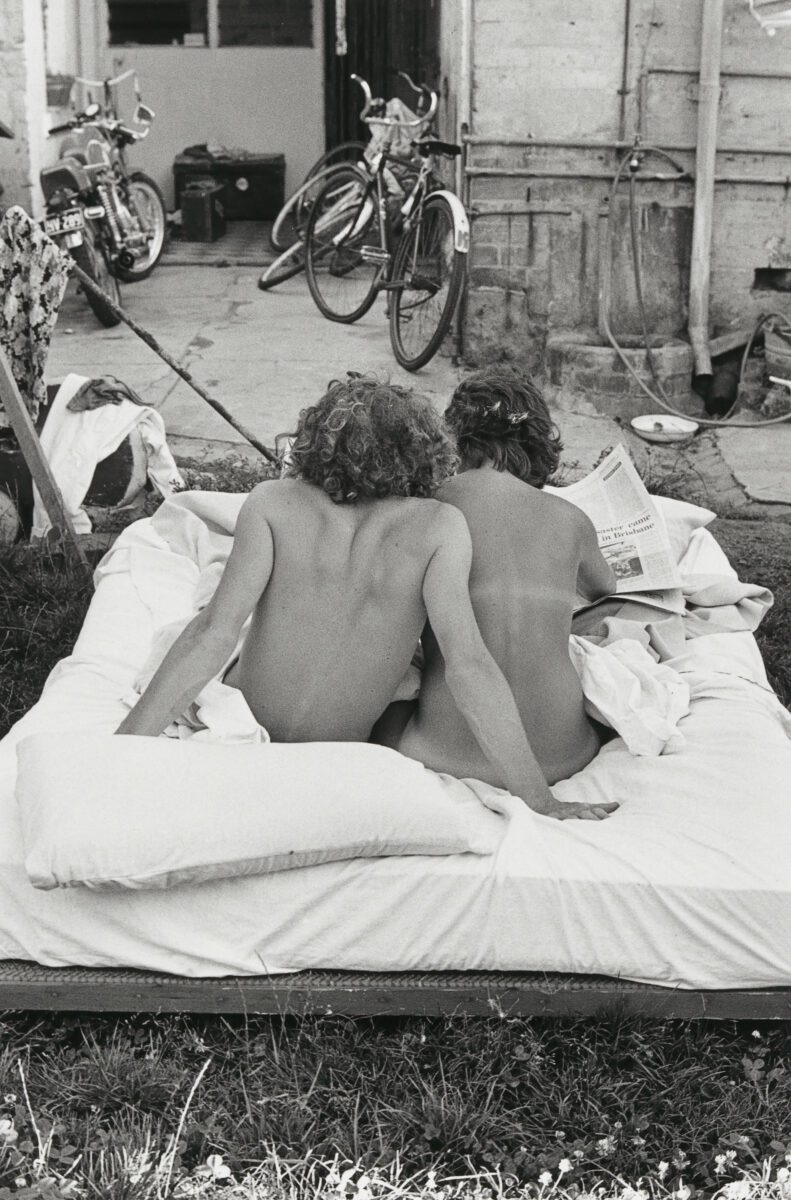

In Melbourne, Ponch Hawkes’s 1970s documentation of communal living and activist spaces conjures a sense of urgency. Her photographs of Gay Pride Week, women’s theatre collectives and political graffiti capture a city in flux. In her images, the personal and political merge into a shared articulation of possibility. The exhibition also presents radical experiments in identity by Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. Their 1930 artist book Aveux non Avenus dissolves boundaries between photography, literature and performance. Cahun appears androgynous and theatrical, unbound by conventional gender expectations. These images anticipate contemporary dialogues around fluidity and self-invention, revealing that such explorations have a deeper history than commonly assumed.

Patterns emerge as atmospheric threads. There is the camera as witness, documenting lived realities: Lange’s migrant labourers, Álvarez Bravo’s washerwomen, Hawkes’s activists. There is the camera as collaborator, where women like Miller, Maar and Lucia Moholy shaped modernist visual language. There is the camera as instrument of self-inquiry, seen in Bing’s mirrors, Woodman’s staged reveries and Cahun’s shapeshifting personas. And there is the camera as agent of radical seeing, through which Florence Henri, Germaine Krull, Tokiwa Toyoko and others pushed photography toward abstraction and experimentation.

Women Photographers 1900-1975 ultimately proposes a reorientation of photographic history. By foregrounding these works, the NGV signals the necessity – and urgency – of redressing archival omissions. Many of the pieces on display have entered the collection only recently, recognising that the canon is not fixed but continually evolving. The exhibition’s timing, coinciding with the 50-year anniversary of the United Nations’ International Women’s Year in 1975, adds another layer of resonance. This is not merely a retrospective but an act of reframing. It suggests the past still has new stories to tell.

In the end, the exhibition offers more than a celebration of artistry. It presents a tapestry of perspectives that expands our understanding of modernity itself. These photographs – intimate, political, experimental, lyrical – become a record of lives lived and worlds observed, illuminating the remarkable legacy of women who shaped the camera’s gaze long before they were fully acknowledged by history.

Women Photographers 1900–1975: A Legacy of Light is at NGV, Melbourne until 3 May: ngv.vic.gov.au

Words: Simon Cartwright

Image Credits:

1&6. Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California 1936, printed c. 1975 gelatin silver photograph 49.4 x 39.6 cm (image) 50.6 x 40.7 cm (sheet) Purchased, 1975.

2. Olive Cotton, Teacup ballet 1935, gelatin silver photograph, ed. 21/50 36.0 x 29.2 cm (image) Purchased from Admission Funds, 1992 © Courtesy McInerney family and Josef Lebovic Gallery, Sydney.

3. Ponch Hawkes, No title (Summer night in the backyard at Falconer Street )c. 1975, gelatin silver photo 30.3 x 20.3 cm (image) 38.3 x 27.9 cm (sheet) Purchased NGV Foundation, 2018 © Ponch Hawke.

4. Barbara Morgan, Martha Graham: Letter to the world, 1940 gelatin silver photo (48.3 × 39.4 cm) Bowness Family Fund for Photography, 2024 © The Estate of Barbara Morgan.

5. Trude Fleischmann, The actress Sibylle Binder, Viennac. 1926 gelatin silver photograph 21.9 x 16.0 cm Bowness Family Fund for Photography, 2022 © Estate of Trude Fleischman.

7. Lillian Bassman, More fashion mileage per dress, Barbara Vaughn, Harper’s Bazaar, New York 1956, gelatin silver photograph, ed. 13/25 43.1 x 60.9 cm (image) 50.8 x 56.5 cm (sheet) Gift of Krystyna Campbell-Pretty AM and Family through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 2023© Estate of Lillian Bassman.