Yemeni-Egyptian-American artist Yumna Al-Arashi (b. 1988) creates work with a singular purpose: to oppose the oppression and stereotyping of women worldwide. The artist uses a range of media – photography, book, sculpture – to explore how the Arab world is depicted, question the legacy of colonialism in our thoughts and contemplate matriarchal traditions that are all but lost. Huis Marseille presents Al-Arashi’s first solo museum exhibition, titled Body as Resistance, which brings together her entire oeuvre. Featured works include dyptich Axis of Evil (2020), which depicts four women from the countries designed “rogue states” by the US government and Shedding Skin (2017), made in a bathhouse in Beirut, emphasising female solidarity and reappropriating the “Orientalistic view of the hamam.” A particular highlight is the 2024 artwork in book form, Aisha, to which an entire gallery is devoted. The piece is inspired by three surviving photographs of her Yemeni grandmother, which prompted Al-Arashi to research the vanishing tradition of facial tattoos in older generations of North African women. Aesthetica spoke to the artist about the show and what it means to use the body as a means of resistance.

A: How did you first begin working behind the camera?

YAA: I started using photography to understand my surroundings and the dynamic of living between the US and Yemen – learning about the political atmosphere, and how images were being made and consumed.

A: You’ve spoken about the “violence” embedded in photographic language: capturing, shooting, taking. How do your works disrupt conventional power dynamics between image-maker and subject?

YAA: It’s very important for me to be able to have conversations with people before a camera is introduced into the process. I commonly ask people how they want to be portrayed and what it is that they want to be seen as (or not seen as). So when I speak about photography, I think about it as a process of creation with whoever is in front of the camera, whether it’s another subject, me or even with landscapes. A process that’s “collaboration” or “making” instead of “taking” or “capturing” is paramount. Sometimes, this extends to self-portraits, in which I photograph myself as a way of replacing a “model.” If there’s a specific thing I’m trying to say, sometimes it’s just easier for me to use myself, because it’s me who wants to say it.

A: You’ve cited the early years you spent in Washington DC following the attacks of 11 September 2001 as “anchoring politics in your identity.” Could you tell us more about this?

YAA: After 9/11, images became – even more than they had already been in the past – such a force for persuading the public. As a young person growing up surrounded by conflicting imagery around who I am and the people that I come from, it was really hard for me to unlearn what I was being shown in media. Thus, it became important to me to use this tool myself to challenge the narratives around me.

A: Much of your work challenges stereotypical depictions of Arab women. What kinds of images were you most intent on resisting?

YAA: There’s an anecdote that I like sharing on this topic. Just before the invasion of Afghanistan, there was an event where Oprah Winfrey unveiled an Afghan woman on stage at a “feminist event,” and press photos of the event were widely circulated afterwards. It’s interesting to me because it made me realise that being photographed or representing something in the US, even if you are a Black person or an Arab person, means that you’re oftentimes plugged into these roles to serve a larger narrative. So it became clear to me from that moment that, as Audre Lorde puts it, you “can’t dismantle the oppressor’s house with the oppressor’s tools.” You can’t work within their narrative to change your own. That became a big starting point for me to figure out how I can challenge a lot of these narratives through simplicity and imagery. Because the pictures we often see are super simple – they’re not even staged photographs, just press shots from an event. Yet, capturing something in that way and have it spread in the media has the same effect. Western Asia, Central Asia and North Africa are seen as having made war in the USA, and those of us who are from these countries are grouped together in one narrative of “we must liberate these women.” Although that image with Oprah depicts an Afghani woman, which I am not, I still felt very close to that narrative. So I try and resist these monolithic portrayals of Arab women.

A: Female solidarity is a recurring theme of your work, particularly in Shedding Skin. What draws you to spaces where women gather collectively?

YAA: Put simply: a lack of men.

A: Aisha began with three photographs of your grandmother. At what point did this personal starting point expand into a wider, transnational project?

YAA: The shift occurred after the war in Yemen made travel impossible. My cousin sent me three low‑resolution WhatsApp images of my grandmother and I realised that the pictures didn’t show the thing that I remember the most: her tattoos. The images were these little passport-sized photographs to begin, they were blown-out and already disintegrating quality-wise, then also compressed by Whatsapp (which is also says something interesting about how we communicate through such distance and war). That begged this whole question of how a photograph represents somebody, or fails to do so. My memory was challenged by these images, where when I was young I was always told that image is truth. I started to think more deeply about what archives mean, be they personal or collective, and how they carry so much weight around the way that we define people. That’s when the wider project of Aisha began.

A: Facial tattoos appear throughout Aisha as markers of identity and memory. What did you learn by following this tradition across different regions?

YAA: That I can never understand what these tattoos mean in their entirety, because each woman had their own story around their bodies, different experiences in life and that’s really hard to define. I like that my book gives the space for the nuances and the opacity that all of these individuals deserve.

A: What do you hope visitors take away from the show?

YAA: I hope that people are able to really understand the process of my relationship to imagery, which reflects a larger story of photography in this world, and that it makes them uncomfortable enough to try to understand more, because it will definitely make some people uncomfortable – it goes from a series of veiled women to completely nude imagery of me. And if you look at those things in their extremities, it can be quite shocking. But there’s a very strong storyline for visitors to take note of, so I hope people understand that there is a need right now to for us to challenge the way that we perceive women. I don’t think that’s necessarily tied to the Arab or Muslim body, but generally how we consume images of women.

Yumna Al-Arashi: Body as Resistance is at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam from 14 February – 21 June: huismarseille.nl

Words: Emma Jacob & Yumna Al-Arashi

Image Credits:

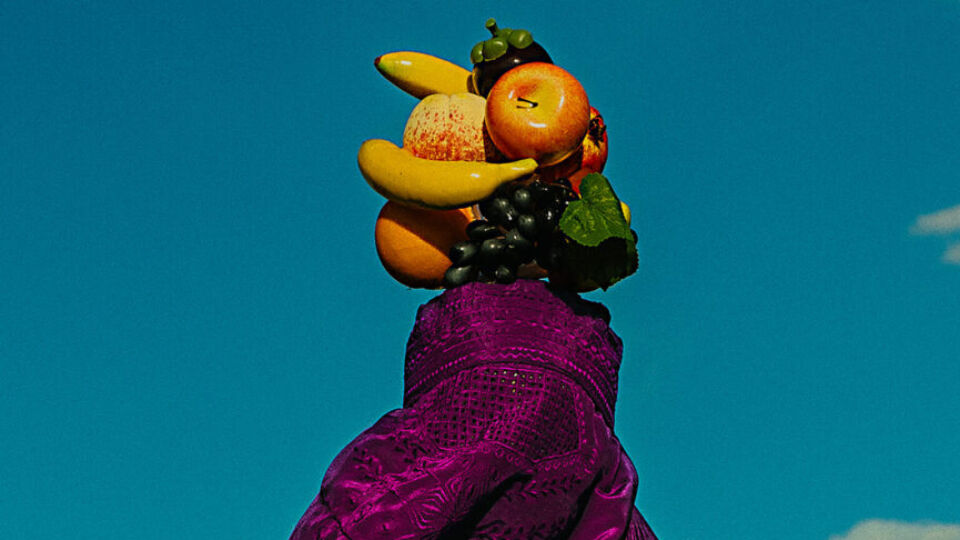

1. © Yumna Al-Arashi, I Am Whoever You Want Me to Be, 2018 from the series I Am Who I Am Who Am I.

2. © Yumna Al-Arashi, Axis of Evil I, 2020, from the series, Axis of Evil.

3. © Yumna Al-Arashi, Northern Yemen II, 2013, from the series, Northern Yemen (2013–2014).

4. © Yumna Al-Arashi, Untitled, 2020.

5. © Yumna Al-Arashi, Northern Yemen I, 2013 from the series, Northern Yemen (2013–2014).