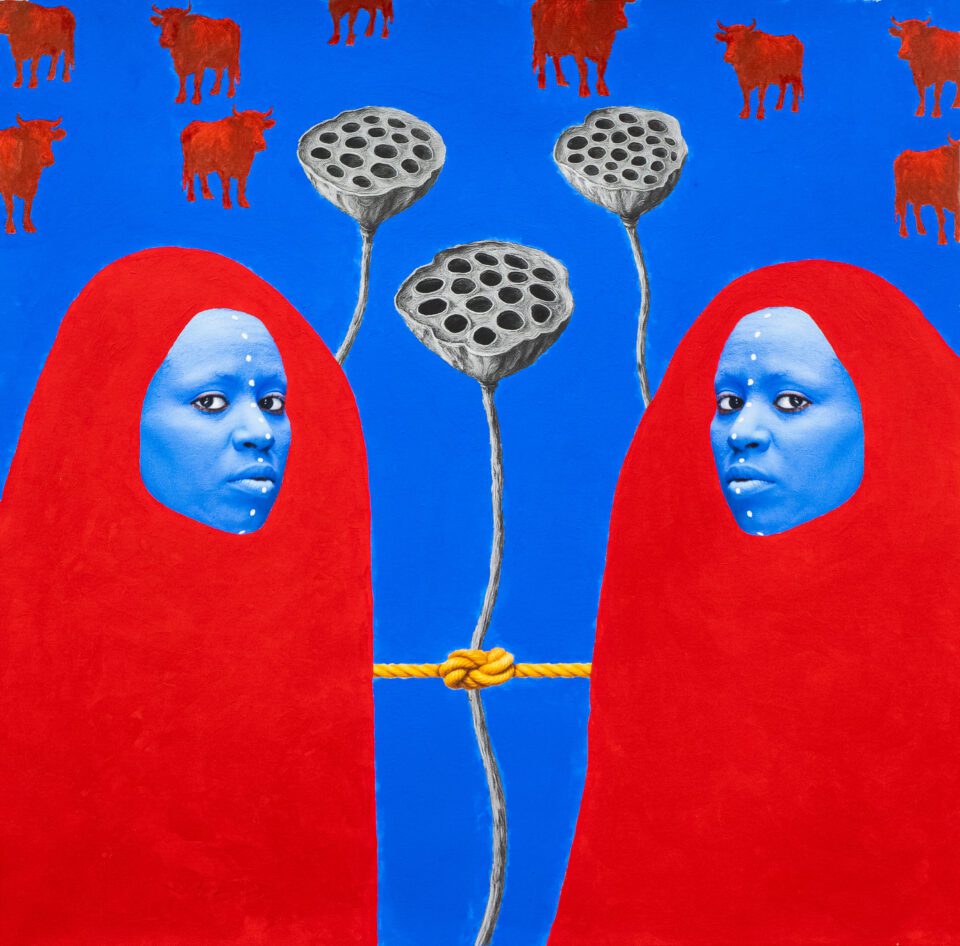

For 25 years, Aïda Muluneh has been a distinctive voice in contemporary photography, recognised as a leader in her field and a change-maker in the African artistic landscape. Her vivid and carefully staged photographs of painted figures in surreal settings draw on African iconography, architecture and textiles, creating visual narratives that blur the boundaries between photography, painting and performance. Muluneh’s work has been exhibited across the world, including at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Photographers Gallery, London and C/O Berlin. The artist also founded the Addis Foto Fest, the first international photography festival in East Africa, as well as The Africa Foto Fair. In 2019, she became the first Black woman to co-curate the Nobel Peace Prize exhibition. Her reach and influence are almost unparalleled. Now a new series, created using silkscreen printing and hand-painted techniques, is on display at Efie Gallery, Dubai. We caught up with the artist to discuss how her practice has changed over the past quarter of a century and how this series marks the next stage in her creative evolution.

A: How did you begin working behind the lens?

AM: It started in the darkroom during high school in Calgary, Canada. Learning to develop and print my own black-and-white images introduced me to photography as a physical and deliberate process, not simply an act of capture. That early experience shaped my understanding of the medium as something made by hand and intention. Later, my training in photojournalism sharpened my ability to observe the world closely, but over time I felt drawn to using the camera to question what remains unseen.

A: You’ve been at the forefront of contemporary photography for 25 years. How has your practice developed over that time?

AM: My practice has shifted from documentation toward construction. I began by engaging with reality as it unfolded but gradually moved toward creating images that operate as symbolic spaces, rather than records of specific moments. Over time, I became more interested in building visual worlds that hold memory, history and emotion. This Bloom I Borrow collection marks a significant point in that evolution, as it reflects both a conceptual deepening of my work and a return to tactile, analogue processes.

A: You’ve described this show as an “excavation of memory and emotion.” Tell us more about this.

AM: This body of work emerged through a slow, inward process of reflection. The images don’t respond to a singular event but grew out of accumulated memories and emotional states. I describe the series as an excavation because it involved uncovering layers that were not visible, allowing fragments of experience to surface and take form. They do not illustrate specific narratives; instead, they create space for viewers to engage with their own interpretations, revealing meanings that may extend beyond my conscious intent.

A: Your images often explore dualities – visible vs hidden, power vs vulnerability, faith vs transformation. Which duality felt most urgent for this exhibition?

AM: The most significant tension in this exhibition is between visibility and concealment. The works exist in a space where revelation is partial and deliberate. They acknowledge that transformation does not require full exposure, and that strength often resides in what is protected or withheld. This balance reflects the emotional landscape of the work itself, grounded yet guarded.

A: Your photographs are rich in symbols such as eyes, keys, masks and ancestral motifs. How do you decide which symbols to include and what do they mean to you personally?

AM: They emerge intuitively through the process, rather than being predetermined. Eyes often reference awareness and perception, both inward and outward. Keys suggest access and transition, while masks speak to protection and the negotiation of identity. Ancestral motifs ground the work in continuity, acknowledging that personal experience is always connected to broader histories. These symbols are intentionally open-ended, functioning as entry points rather than fixed meanings.

A: Your work frequently explores womanhood and identity. What is the most challenging part of expressing these themes through staged photography?

AM: The challenge lies in resisting simplification. Staged photography risks reducing complex experiences into singular narratives. My aim is to create images that hold contradiction and ambiguity, allowing women to exist as layered and evolving subjects rather than symbols of a single idea. Maintaining that complexity requires careful and ever-shifting balance between control and openness.

A: How does the environment you work in shape the final product?

AM: My process moves between working within the confines of a studio and the outdoors. The intention is that the work is never defined by space. Several of my earlier collections in Addis Ababa were produced entirely outdoors, often under the shade of a building. What remains consistent is the construction of the image. The backdrop is a key element in shaping the narrative, alongside colour, the positioning of the models, and the overall composition. Whether the backdrop is built or found within an existing location, the studio, for me, can exist anywhere. Ultimately, the work is about constructing my own visual universes from reality, creating a collage of memory rather than documenting a specific place.

A: Can you walk us through your process, from concept to hand-finishing?

AM: I begin with writing and sketching, allowing the concept to take shape through decisions around model positioning and colour blocking. These ideas are further developed through material experimentation before moving into the photographic stage, which involves constructed sets, costumes and body painting. Once the image is printed on canvas in my studio in Abidjan, I worked with Ahmad Makary at The Workshop DXB in Alserkal Avenue to silkscreen the work onto canvas and explore the possibilities of image transfer. This final stage reworks the photographic surface, creating space for intuition, materiality and the physical presence of the hand to shape the finished piece.

A: How do you balance personal narrative with collective cultural memory?

AM: I do not see personal narrative as separate from collective memory. Individual experiences are shaped by history, culture and inherited stories. In my work, these elements overlap rather than exist in opposition. The images create a shared space where personal emotion resonates within broader cultural contexts, inviting viewers to locate their own connections.

A: You’ve played a major role in developing photography infrastructure in Africa through Addis Foto Fest and Africa Foto Fair. How has the global conversation around African photography evolved in the last decade, and what shifts would you like to see next?

AM: Over the past decade, photography in Africa has increasingly been recognised for its conceptual depth and authorial voice rather than being confined to documentary frameworks. Photographers are asserting greater control over how their work is produced, contextualised and circulated. Moving forward, I would like to see sustained investment in local infrastructure education, media, publishing and archiving that enables long-term artistic and economic sustainability. Building these ecosystems is essential for ensuring that African photographers define their own futures.

This Bloom I Borrow is at Efie Gallery, Dubai until 5 April: efiegallery.com

Words: Emma Jacob & Aïda Muluneh

Image Credits:

1. Aïda Muluneh, The Hidden Learns to See, 2026. Digital photographic print, acrylic on canvas_77 cm x 98 cm. Courtesy of the Artist and Efie Gallery.

2. Aïda Muluneh, This Bloom I Borrow, 2026. Digital photographic print, silkscreen, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Efie Gallery.

3. Aïda Muluneh, In The Season of Sorrow, 2026, Digital photographic print, silkscreen, acrylic on canvas, Courtesy of the Artist and Efie Gallery

4. Aïda Muluneh, The Conference, 2025, digital photographic print, silkscreen, acrylic on canvas, 61 x 61cm, courtesy the artist and Efie Galllery, Dubai.