Jennie Baptiste (b. 1971) began documenting the fashion, music and youth culture of London’s Black British diaspora in the 1990s. The artist roots her photographic process in authenticity, often turning her lens to the “everyday icons” within vibrant music cultures like dancehall and hip-hop. A new exhibition at Somerset House is the biggest retrospective of Baptiste to date, rightfully placing her within the canon of pioneering 20th century artists. The expansive show brings together highlights from Brixton Boyz — a late-1990s series of street portraits celebrating camaraderie and style among young Black men in South London — alongside Dancehall, Baptiste’s ongoing chronicle of the capital’s vibrant dancehall scene, and Black Chains of Icon, a conceptual body of work that interrogates Black identity through suspended images and text. Aesthetica caught up with Baptiste, to chat about her remarkable, three-decade career.

A: What did your journey into photography look like?

JB: My career really started when I was a student. I was in the second year of my undergraduate degree when my work was published in a magazine for the first time. During that time, I was also volunteering for the local newspaper – the Wembley and Brent Times – as a photographer. It was led by young people, so it focused on youth-related issues, from news stories to entertainment. I would cover the photography side of things as well as sometimes doing a bit of writing. But my love of the craft goes back even further, to when I was at school. A group of us discovered a dark room and studio, whilst doing our A-Levels and went to the head teacher to ask why we, as art students, weren’t doing photography. We were told it was for adult evening classes, but we persisted and eventually were able to do a photography GCSE. That’s where I started learning how to process film and the foundations of printing black-and-white images.

A: Who, or what, are your biggest inspirations?

JB: When I was first starting out, I tried different types of photography because I wasn’t sure which aspects of it I liked. I would do landscapes, portraits and vox pops. From that, I found that I really liked portraits, as I enjoyed the rapport that you have with the subject. I also had a passion for music. I had a collection of records and vinyl and as a youngster, I would look at the images and read the credits of who had taken them. There were some photographers I liked purely because of like the style and aesthetic of their work. Albert Watson is definitely one of my favourites from way back, as well as James Van Der Zee.

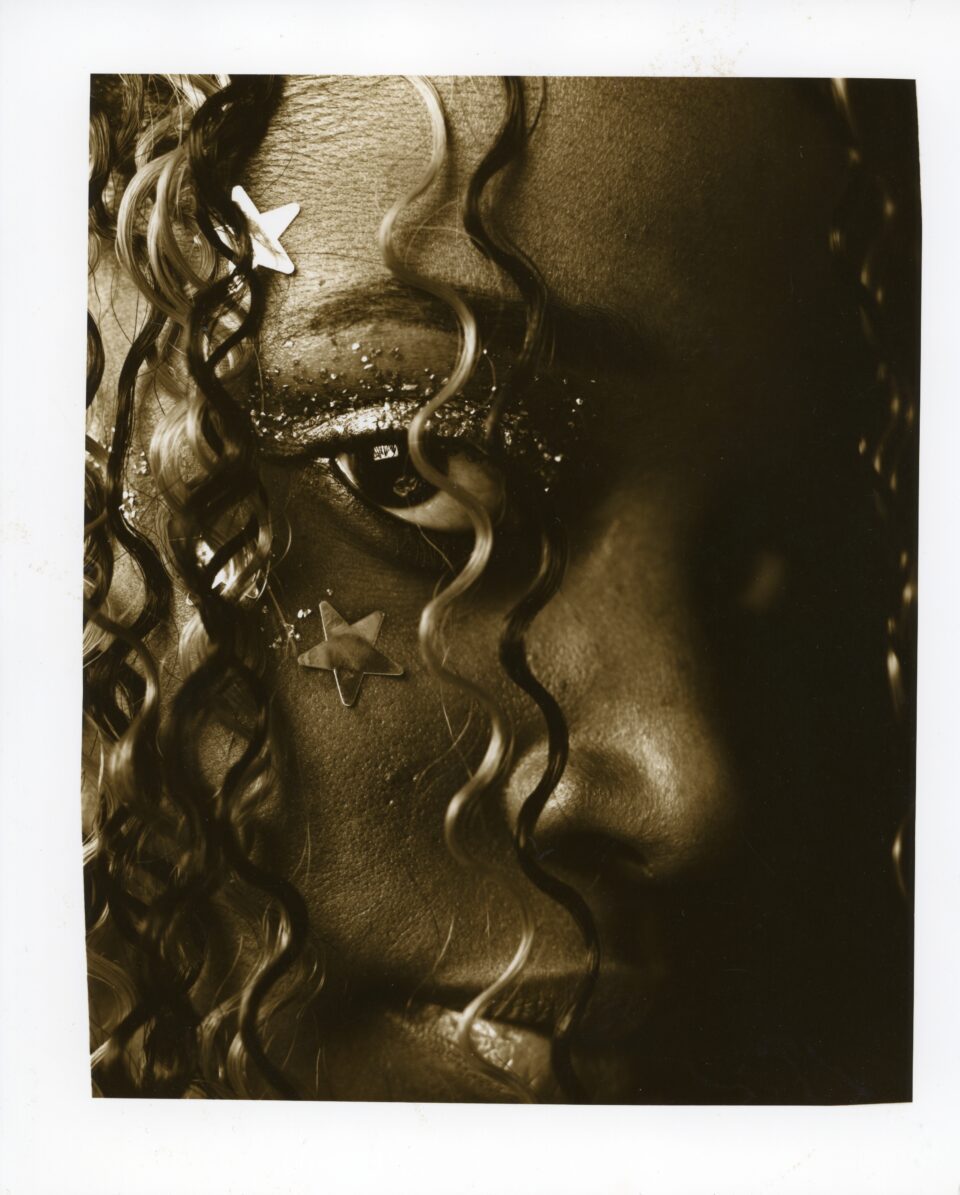

A: What drew you to London’s dancehall scene, as well as the rise of hip hop & R&B?

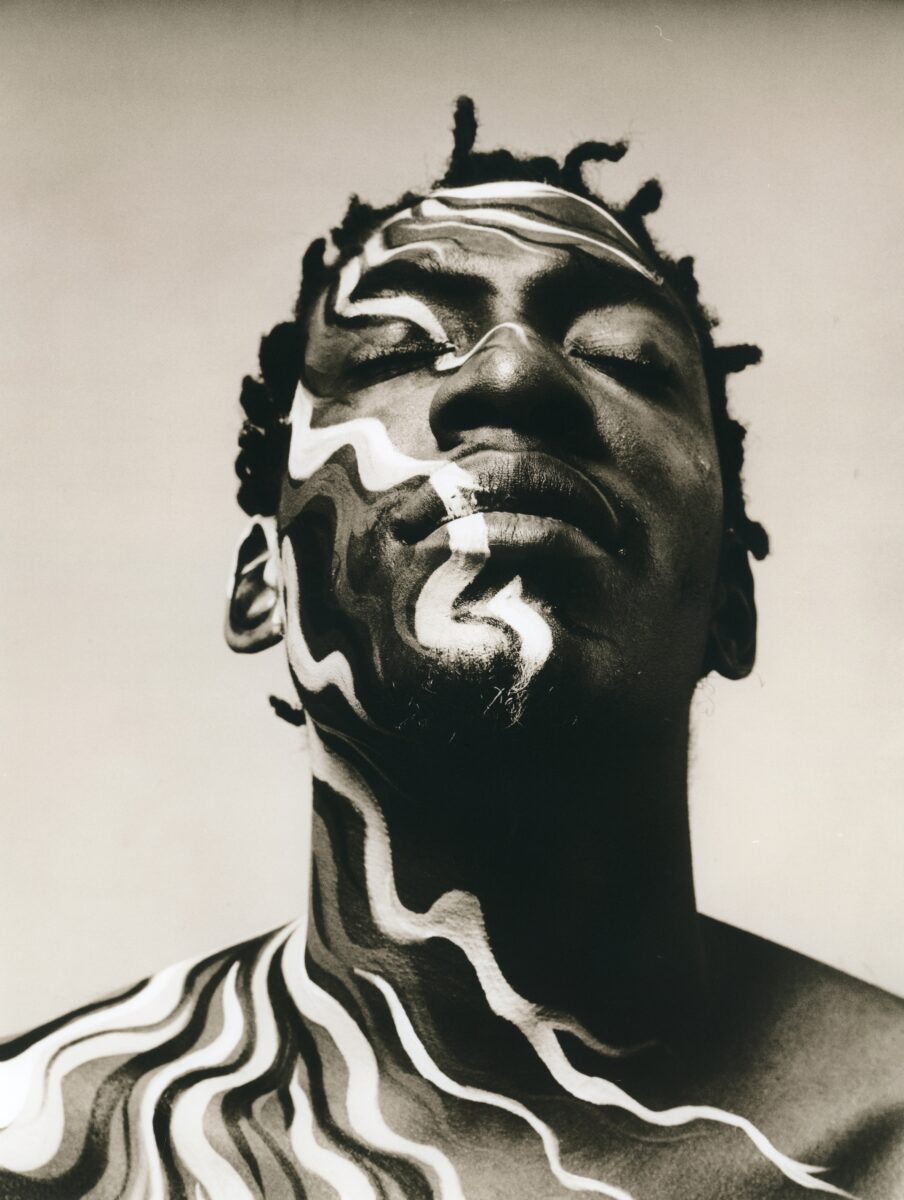

JB: In my teens, my pocket money was spent on music magazines. I grew up in the 1980s, so I was a part of the MTV generation, when music videos were becoming really popular for the first time. I bought magazines like Smash Hits, The Face and i-D, all of which covered youth culture, music and fashion. My influences growing up came from within my family as well. My sisters were into different genres and as the youngest, I was exposed to all of them. When I started photography professionally in the 1990s, dancehall and hip hop were rapidly rising into mainstream. Both had a lot of commercial imagery that was already out there, and I wanted to put my own spin on it. I brought people who were into dancehall into the studio, which was something I hadn’t seen done before. At the time, a lot of the images were in clubs or on the street, and I wanted to capture the vibrant, bold, confident community in a different way. It was the same thinking with hip hop, I wanted to go beyond images which took a male musician and made sure he looked really macho and blinged out. My aim was to try and get the artist’s personality to come through.

A: Music and youth culture is always shifting and evolving. How do you keep up?

JB: Intuition plays a big role in my work and so does research. I always try to look for an angle that hasn’t been done before because otherwise, what’s the point in doing it? I need to bring my own spin and originality; whatever it is I’m trying to create. I don’t tend to think “it’s moving so quickly, it’s changing. How am I going to fit in?” I just do what I feel is right in that particular moment. For example, I worked on one series, on and off for years, starting in 1993. I consciously decided to do that because I was part of that scene, and I’d see things happening and think “that’s changed slightly, it might be interesting to capture a different aspect of it.” One example was a project I did in Notting Hill, around Portobello Market, and it centred around a woman named Pinky. I was aware of her, but hadn’t seen her on TV, so we met up and I decided that I wanted to do a portrait of her. She’s a very unique person and was prominent in the culture at that time. The shoot was done in her home, and obviously it’s not everyday that you go into someone’s house and all you see is different shades of pink. It was very vibrant and striking.

A: You’ve photographed some remarkable people, including Roots Manuva, Estelle, Mary J Blige, Ms Dynamite, NAS and Jay Z. Do you have a particular portrait that comes to mind as a favourite?

JB: I’m really proud of the Roots Manuva photograph. I did that more than 20 years ago and now a new generation of people have discovered it because its currently on display in the 1990s room at the National Portrait Gallery. At the time, camouflage was a huge fashion trend, it was everywhere. So, my editor asked me to speak to Rodney (Roots) about doing some camouflage makeup. He was cool with it and said he trusted me, which is all you want as a creative. I have been very fortunate in that I have had a lot of creative control. There wasn’t a tight brief. It was like, “okay, you’re going to photograph Jay Z, what do you want to shoot?” You’d liaise with the record company, and then it’d just be me and the artist.

A: The show spans three decades. What was it like to look back over your career?

JB: It was months and months of going through archives of thousands of images. It was overwhelming at first because I’d never gone that far back. You become used to doing one thing, putting it down, then moving on to the next. I’ve never done an exhibition of this size before, so there were aspects of it that was really fun, like seeing images of famous people and thinking “oh, I’d forgotten I’d photographed them.” There were some really great moments where the memories were coming back and it was an opportunity to reconnect with people. It’s a very emotional journey, putting it all together and bringing them to a new audience. Revolutions @33 1/3 rpm, which hasn’t been shown in 26 years, has its own room. The series is about London hip hop DJs back in 1999 and it was a huge exhibition at the time. At that point, DJs weren’t seen as celebrities. I had decided that I didn’t want to do an exhibition on musicians, because we all know who they are. I thought: Let’s do something different, what’s the angle? I landed on the DJs, because they’re the ones behind the beats helping to cultivate and mix the tracks. It’s been great to reconnect with the people in the images, some of them I’ve keep in contact with over the years and others I haven’t seen since, but nine out of the 11 I photographed are going to be at the exhibition. They’ve all made mixtapes, so the audience will have the chance to experience music from that era.

A: Rhythm and Roots also features Black Chains of Icon, a powerful conceptual series exploring themes of Black identity, resilience and legacy. Could you tell us a bit more about these works?

JB: I did that work very early on, in 1994. You can see that I’m visually influenced by hip hop and youth culture. At the time, you were seeing piercing, markings shaved into people’s hair and high tops, as well as symbols from sports culture and brands. I came up with the idea for Black Chains of Icon because I wanted to create something that would be powerful in how it was delivered. I didn’t necessarily want a photograph in a frame on the wall. I was fusing identity, heritage and history. When I say identity, I’m talking about going back to colonialism where ID tags were used, but then ID tags or dog tags came into fashion. I used a lift developer that was a few days old and I experimented to get a particular effect because I wanted the image to look as if it was taken many years ago. The series itself is relatively small, it’s not that many pictures, but it’s mounted on aluminium plates and hung on chains and suspended from the ceiling. There are quotes from Black speakers embedded on a plate hanging just below the image.

A: How do you see the role of photography in improving representation?

JB: Black photographers have always been around. I was featured in a book called Shining Lights, which was done by photographer Joy Gregory. It came out last year and featured just over 50 Black female photographers. There are pioneers that came before me. There are people like Joy, there’s people like Charlie Phillips, there’s James Barnor, who’s now in his 90s. It’s more a question of: are people getting the opportunities? Is the work being spread out equally and inclusively?

A: What do you hope audiences take away from the exhibition?

JB: I want to get across the message, especially to photographers, to do what feels right for you authentically. It’s a journey and it can be a long one, and we don’t know how it’s going to turn out. You just keep doing what you’re doing. The industry has changed so much now, from analogue to digital, so it’s about carving out a space and trying to think: how can I be distinctive? How do I be different from what’s out there? Because people are constantly seeing images on their phone, what’s going make someone want to stop and look and take some time and look into who I am.

Jennie Baptise: Rhythm & Roots is at Somerset House, London until 4 January: somersethouse.org.uk

Words: Emma Jacob & Jennie Baptiste

Image Credits:

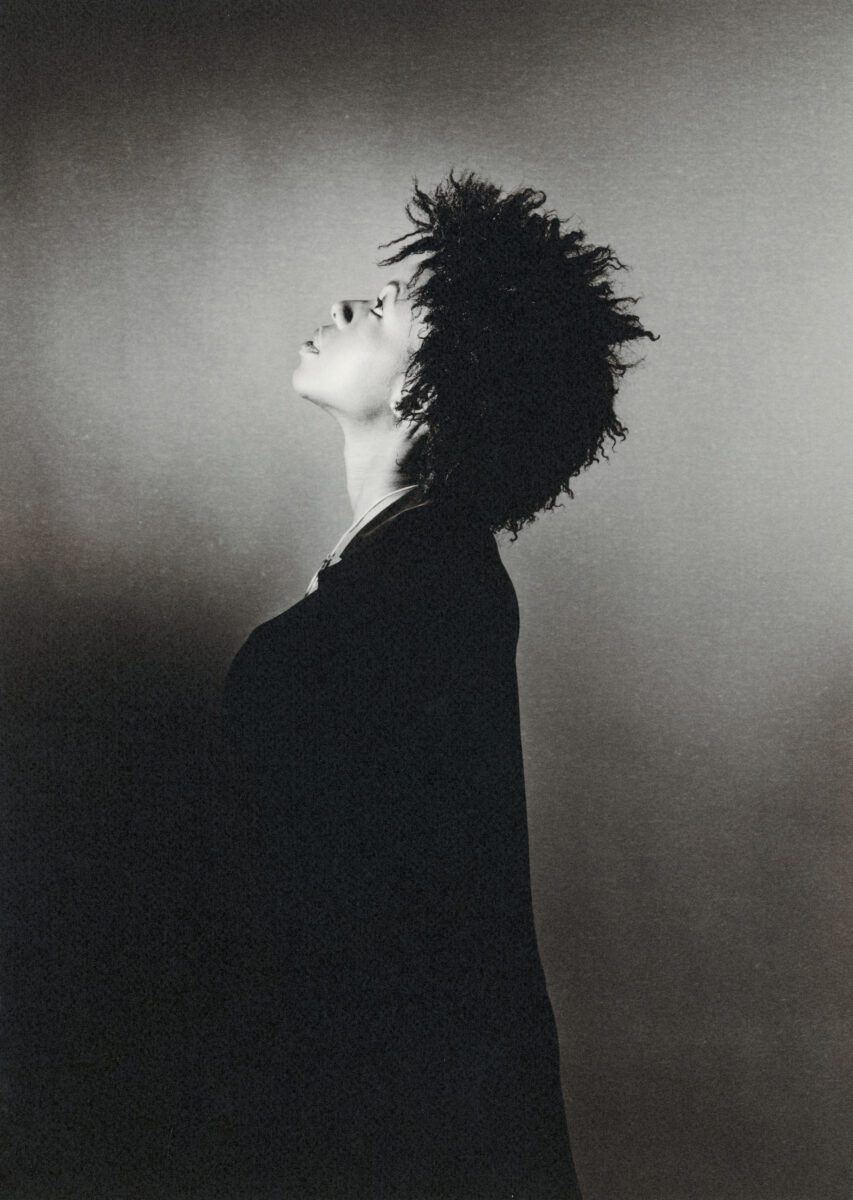

1. Jennie Baptiste, Butterfly Queen, Taken from the series Ragga dancehall. (1994).

2. Roots Manuva. Fatboss magazine (British Hiphop magazine) commission. 1999 Courtesy of Jennie Baptiste.

3. Ragga. Taken from the Ragga dancehall series 1993. Courtesy of Jennie Baptiste.

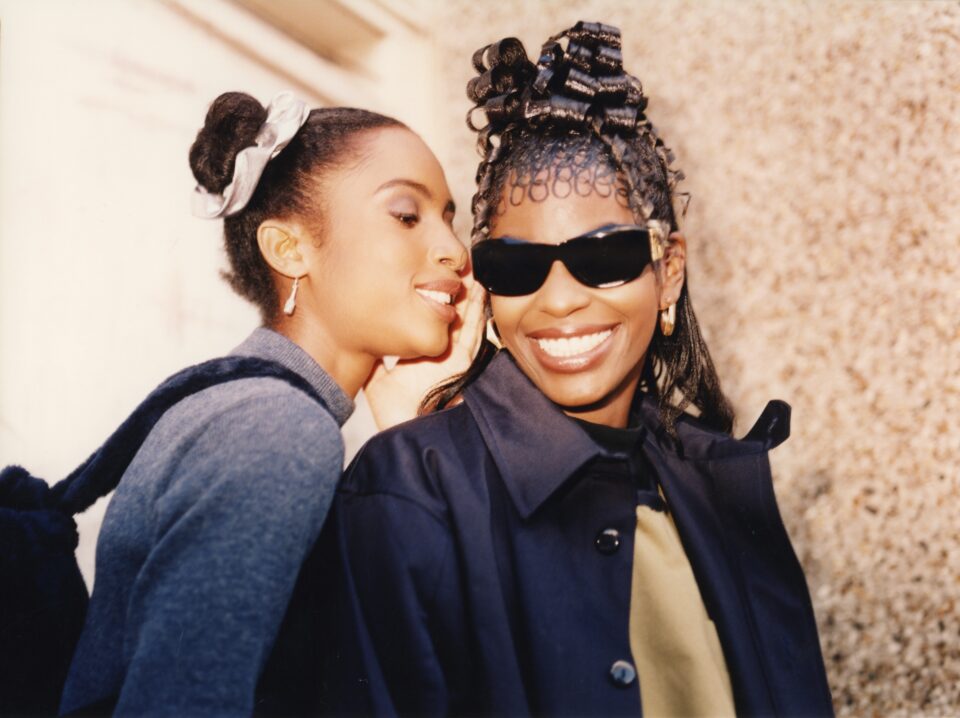

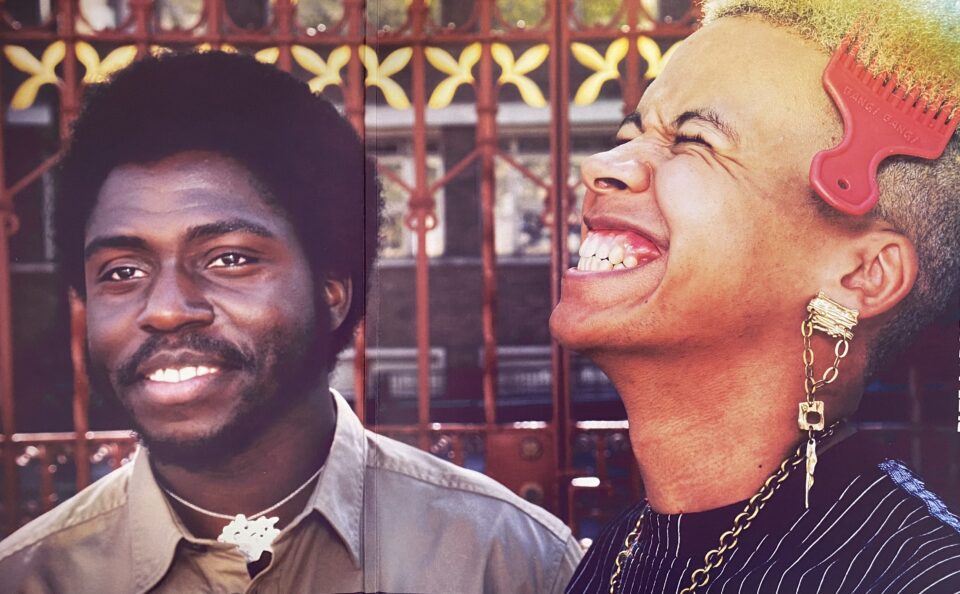

4. Friends, Wale Adeyemi Fashion Shoot. Courtesy of Jennie Baptiste.

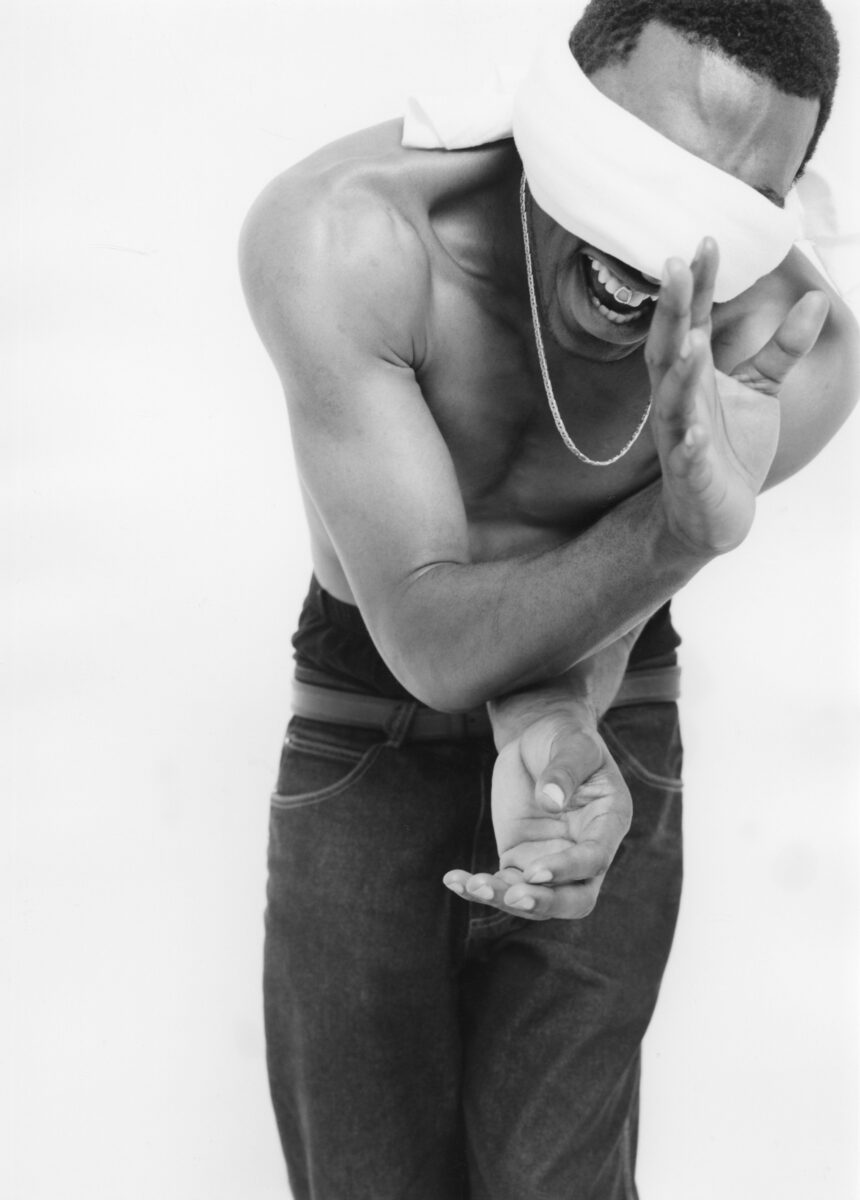

5. Mental Health & Black men. Fragility, 1999 Courtesy of Jennie Baptiste.

6. Black women & hair, Afro Beauty, 1998. Courtesy of Jennie Baptiste.

7. Blue Lab Beats, Blue Lab Beats. Courtesy of Jennie Baptiste.