The late Brigitte Kowanz was one of the most important and pioneering European conceptual artists to work with light. This autumn, Albertina Museum, Vienna, launches the first major posthumous survey of her four decades-long career. Light is what we see is a “magical and revelatory” show, according to Angela Stief, who is the curator alongside Kowanz’s son, Adrian. Comprising 88 pieces, the retrospective spans never-before-seen early Polaroid photographs, to some of the artist’s most well-known works like Morsealphabet (1998) and Email 02.08.1984 03.08.1984 (2020). It shows her prescience of the ever-aggressive, increasing virtualization of society we see today. At the same time, it positions her as a major player in the history of light art, who consistently pushed the field beyond mere aesthetics, towards a medium that could be critical of technology and politics.

Born in Vienna on 13 April 1957, Kowanz studied at the city’s University of Applied Arts, working on installations and media that weren’t always met with openness or understanding. She started out by integrating phosphorescent and fluorescent pigments into traditional painting. During her studies, despite tentative reactions, Kowanz found an important mentor in painter and sculptor, Oswald Oberhuber. In one of his classes, she met Franz Graf, who would become her partner of several years, living and working alongside her, especially deepening her investigations into phosphorence and fluorescence. The pair even collaborated for the 1984 Venice Biennale – this work, and other collaborations between them, is showcased in the first section of Albertina’s new exhibition.

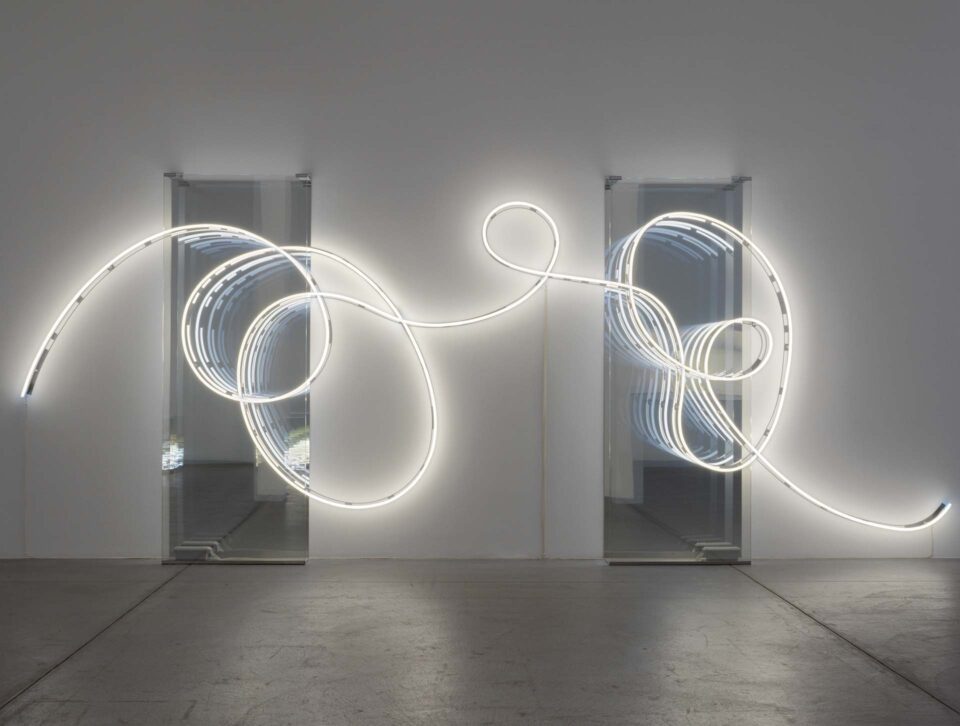

Kowanz began to garner international attention in the 1980s, participating in other major shows, such as the Triennale di Milano, Westkunst’s Heute section, and the Paris Biennale. In 1987, she represented Austria at the São Paulo Art Biennial. By this time, she had moved away from painting entirely, exploring light bulbs, lamps and other everyday sources of illumination as materials instead. The resulting works were materially simple but conceptually radical: they approached light as a standalone, autonomous artistic material. Around the same time, Kowanz also began working with neon tubes, enabling her to “draw” in space, as exemplified by the Speed of Light series, developed in 1989. This was pivotal moment, where she transitioned from painting surfaces, towards sculptural and spatial light environments.

During the 1990s, Kowanz started to integrate language systems into her practice, particularly Morse code, binary and textual fragments. She inscribed and embedded dots and dashes into neon tubes or LED strips; in this way, she alchemised basic communication into light, creating a complex aesthetic presentation out of everyday tech. From here, Kowanz’s work grew in scale and audience, and she realized over 50 public installations from 1992 onwards. “She created situations in which light could reveal itself, making its dual role tangible – both as a physical phenomenon and as a carrier of information,” Adrian says. “In this sense, her oeuvre connects to much broader philosophical questions.”

The year 1995, in particular, was mammoth for the artist. Her son, Adrian, was born. Kowanz debuted her first work involving Morse at the Venice Biennale, with the message “Light is what we see” – the quote reproduced for the title of Albertina’s show – written in code, then translated into light.

Kowanz also made www in 1995, a renowned conceptual piece – her first referencing the World Wide Web – where neon tubing is bent into the shape of the letters “www”, against mirrored glass. The neon feels as cold as the technology it is referencing, whilst the mirror multiplies the letters into an infinite regress. It was made before the Internet had begun metastasising through everyday life, and you can’t miss the prophetic metaphor for what was to come. www crystallised a turning point for Kowanz, whilst further cementing her visual vocabulary: from her use of light as material, to exploring language as code (www was as an increasingly ubiquitous acronym, both linguistic symbol and technological instruction), and a meditation on the rapid multiplication of new technologies. From this point, sustained engagement with digitisation, a rapidly evolving social, technical and political phenomenon, spread throughout her practice.

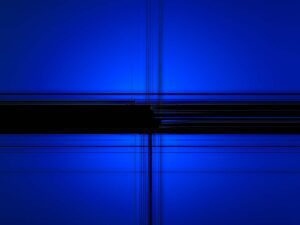

The second part of the Albertina retrospective – “the concluding highlight”, as Stief puts it – includes elements of underground club culture. There’s an immersive black-light room, which takes reference from new wave music, hallucinogenic experiences and punk, reflecting a time where people were just starting to try to comprehend the huge changes digitisation was bringing to almost every facet of society. In the art world, this meant mounting interest in virtuality, new forms of experimental filmmaking, video art and digital production. Within this space, Kowanz’s monumental phosphorescent, fluorescent works multiply boundlessly, their impact more breathtaking for their physical and historical context.

“This atmospheric dimension was never about mere effect.” Adrian explains. “Kowanz deliberately created such environments to heighten perception and to allow light to be experienced not only as information, but also as a medium of reflection. In this sense, the mirrored and black-light spaces are as conceptual as they are sensorial – immersive situations that both reveal and question the structures shaping our digitised present.” The space feels otherworldly, because it is a signifier for the creation of a new world – one that is irrevocably digital. It’s also an ambitious curatorial choice for Albertina. “In a museum like this, which has a collection and programme spanning more than 600 years of art history, the work challenges not only viewing habits but also the conditions under which exhibitions are produced,” Stief explains.

Albertina’s show can be read as a microcosm of the information age – where communication shifted from analogue to networked devices. “Kowanz’s investigations into systems of encoding and transmitting information – from Morse code, often described as the first binary system, to works such as Lichtgeschwindigkeit (Speed of Light) that reflect on the very speed of light as the basis of our digital age – run like a thread through her entire career,” Adrian says. “In this way, she not only anticipated the digitised and virtual information society that has become our everyday reality, but also critically reflected on its conditions: invisibility and visibility, transparency and opacity, acceleration and immateriality.”

One could position Kowanz alongside other artistic pioneers who transformed the ways in which we view art and technology in relationship within an expanding infosphere. In the 1960s, Dan Flavin attached a single, industrial fluorescent light tube at a 45- degree angle to the wall of his studio and called it art, changing our relationship with materials forever. In 1974, Nam June Paik famously coined the idea of an “electronic superhighway”, prophesying media networks as cultural infrastructure. Kowanz brings this vision to life in works that reference key moments in telecommunications: the first email, the launch of Google, iPhones and Wikipedia.

Today, traces of her influence can be seen everywhere – especially in contemporary data-driven art and aesthetics, such as Refik Anadol’s mass visualisations of digital memory. From the maximalist light art of Chila Kumari Singh Burman, to the spiritual installations of Anila Quayyum Agha, the referential work of Cerith Wyn Evans, and the political, confessional neons of Glenn Ligon, light has become a potent tool for communication across the art world. Yet, whilst Anadol and the simultaneous rise of immersive art and environments revel in an overwhelming sense of spectacle, Kowanz’s method was one of distilling, boiling communication down to a luminous essence. At the same time, her work also anticipated more critical contemporary lenses of artists like Felicity Hammond, who probes the politics of image-making in the digital age, particularly by critiquing our reliance on AI.

“In times of the disappearance of reality and the reality of disappearance, of digitalisation, of the virtualisation of the world, and of the ongoing discussions about artificial intelligence, the physical perception of this art is a unique experience bound to analogue space,” Stief says. “Through parables of the unknown, such as reflective endless loops, projections, black light rooms, and plays of light and shadow, the body is thrown back on itself.” The exhibition further prompts the viewer to reconsider modes of categorisation, both in terms of Kowanz’s art and what it stood for. For instance, some of her pieces responded to architectural contexts, such as museum façades and public spaces, where light functioned both as an artistic medium and as a social signifier. One potent example was Beyond Recall (2010-11), a site-specific installation upon the State Bridge in Salzburg. It is dedicated to the many prisoners of war and forced labourers who constructed the bridge between 1941 and 1945.

Brigitte Kowanz passed away in the city of her birth, Vienna, on 28 January, 2022. Her final work, ALWAYS A WAY ALWAYS AWAY, was a public installation on a roof near Zurich’s main railway station. “When looking at the reception of Kowanz’s work, it becomes clear that it was always difficult to categorise – and that was precisely her intention,” says Adrian. “Space was as important to her as light, so she resisted being reduced to light alone. And she was undeniably a pioneer.”

Through her use of mirrored glass and surfaces, multiplying lights and coded systems of communication, Kowanz’s work both preempted and reflected the mushrooming onslaught of digitisation, the Internet and new technology’s massive transformations of society, politics and understandings of the self and the collective. She formed important precedents for more contemporary artists working with similar mediums to elucidate our current world, where AI and changing data flows evolve rapidly by the day. At the same time, Kowanz foregrounded light’s power as a medium and a message that, in her words, “makes things visible but is itself transparent.”

“Her work unfolds at the intersection of conceptual poetry and scientific research: rigorous in its examination of codes, systems, and technologies, yet poetic in its ability to transform abstract structures into sensorial experiences,” her son concludes. “This unique position places her firmly within the international history of light art, whilst simultaneously expanding it into all-new conceptual territories.”

Light Is What We See is at Albertina Museum, Vienna until 9 November: albertina.at

Words: Vamika Sinha

Image Credits:

1&3. Installation view, Lost under the Surface, Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich, (2020). Photo: Stefan Altenburger © ESTATE BRIGITTE KOWANZ / Bildrecht, Vienna 2025.

2. Position – N 46°38´47” E 14°53´31”, (2007/2008). Oermanent installation at Museum Liaunig, Neuhaus. Photo: Lisa Rastl © ESTATE BRIGITTE KOWANZ / Bildrecht, Vienna 2025.

4. More L978T, (2007). Neon, mirror, 170 x 100 x 44 cm. Photo: Peter Kainz © ESTATE BRIGITTE KOWANZ / Bildrecht, Vienna 2025.

5. Brigitte Kowanz, www 12.03.1989 06.08.1991, (2017). Neon, mirror, aluminium, enamel paint 270×670×20cm. The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna – Donation Adrian Kowanz 2025 © ESTATE BRIGITTE KOWANZ / Bildrecht, Vienna 2025, Photo: Stefan Altenburger.