“Queer things do differ from the divine average of mediocrity.” This anonymous quote, first recorded in 1921, opens Queer Lens. This new landmark publication surveys the transformative role of LGBTQIA+ artists in photography. The book features more than 200 works from 157 practitioners, tracing how the camera has been used by members of the community to affirm their culture and identity. Running alongside an exhibition of the same name at Getty Museum, this is a thoughtful endeavor to bring overlooked histories to new audiences. At the same time, it acknowledges that this is, essentially, an impossible task. Co-authors Paul Martineau and Ryan Linkof write: “The excitement and challenge of this project stem from the fact that queer and photography are vastly, almost endlessly multifaceted expansive terms.” The richness of LGBTQIA+ life is palpable, and the pages brim with authenticity.

Queer Lens zooms out, surveying the influence of LGBTQIA+ people on photography since its inception in 1839. The introduction covers huge ground, taking readers back to the first appearance of “queer” in the English language. The adjective appeared in the 16th century meaning “strange,” “odd” or “peculiar”, often used to refer to nonnormative behaviour, dress or lifestyle. It also came to be linked to clandestine, and at times even criminal, activity. As time went on, the word became synonymous with men who have sex with men, and by the 1920s, it was part of a pejorative lexicon levied against homosexual individuals. This brief history lesson is a jumping-off point for a comprehensive look at how queer people have been viewed, marginalised and victimised by society for hundreds of years. Later passages go on to explore the reclamation of the phrase, citing artists like New York-based artistic duo McDermott & McGough, who created A Friend of Dorothy 1943 (1986). The composition included several slurs painted across a bright yellow background. It draws attention to the use of offensive terms when young American men were being drafted during WWII and butch masculinity was highly valued.

Those looking for a quick overview are in luck, as Martineau and Linkof provide a handy timeline before diving into more in-depth studies. The eleven-page chronology blends pivotal moments in art history (“1935 – Kodachrome film is invented and becomes widely used for colour photography and cinematography”), with instances of queer creation (“1978 – Robert Mapplethorpe creates X Portfolio, a collection of sexually explicit photographs depicting the BDSM scene”) and wider political happenings (“1962 – Illinois becomes the first state to remove sodomy from its criminal code”). It’s by no means comprehensive – no single timeline could be – but it offers a formidable starting point for deeper study.

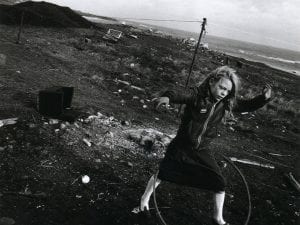

The chapters are similarly organised by time period, beginning with “Nothing but a freak convention: Queer Photography’s Hybrid Origins 1839-1900.” From there, readers are taken through the shifting landscape of LGBTQIA+ rights and artistic expression: from the laws, rules and censorship of sexuality and desire at the turn of the 20th century, through the drag performers of 1920s New York, 1969 Stonewall riots, AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, to today’s ongoing struggle for trans rights. Images include portraits of gay icons of literature, film, music and art, such as Irving Penn’s picture of writer Truman Capote; historic moments like Arthur Tress’ Gay Activists at First Gay Pride Parade; and Rotimi-Fani Kayode’s intersectional snapshots of Black, queer desire. Each chapter is accompanied by a selection of photographs. Works by gay artists are presented alongside those by famous artists whose connection to the LGBTQIA+ community is perhaps less known. One shot by Henri-Cartier Bresson, taken in Naples in 1963, shows two men sitting beside a newspaper stand, one perched on the other’s lap. Elsewhere, WeeGee’s The Gay Deceiver depicts a man in drag, pulling up the hem of their dress and displaying a grin as they climb out of a police van. In bringing together disparate artists, the authors remind readers that there is no actual divide between the history of photography and that of queer art – they are indistinguishable.

Martineau and Linkof are adept at spotlighting intersectionality. In particular, there is a genuine consideration of the lived realities of people of colour. The authors write: “The histories of art have not done enough to acknowledge the immense contributions of queer artists and cultural producers – many of whom fell victim to AIDS at a time of intense hostility, bigotry, and disregard for their lives. This has especially been the case for Black queer artists, who still have not been granted the recognition they deserve.” They draw on one prominent example: Darrel Ellis. The photographer was a contemporary of household names like Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz and Nan Goldin. Ellis had little success or acclaim in his lifetime and sadly died from AIDS-related causes in 1992, at the age of 33. His life and legacy are an important example of the compounding prejudices that people of colour faced: marginalised both in mainstream culture and, often, within LGBTQIA+ spaces.

The book’s closing words come from photographer Catherine Opie. She writes: “my own personal mantra throughout life has been: without representation, there is no visibility.” Queer Lens is an invaluable addition to this ongoing pursuit of fair and equitable representation. The volume is a tour de force, addressing a wealth of topics but managing to give each the time and reverence they deserve. It commits to paper an important collective story of creativity, joy and resistance.

Queer Lens: A History of Photography is published by Getty Publications: shop.getty.edu

Words: Emma Jacob

Image credits:

1. Texas Isaiah (American, active since 2012) Thané, negative 2016; print 2021. Inkjet print. 76.2 × 50.8 cm (30 × 20 in.). Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2021.24.1.

2. Joan E. Biren (American, b. 1944), Priscilla and Regina, Brooklyn, NY, negative June 1979; print 2019. Inkjet print, 48.1 × 37.5 cm (18 15/16 × 14 3/4 in.) Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum © JEB (Joan E. Biren).

3. Arthur Tress, Gay Activists at First Gay Pride Parade, Christopher Street, New York, NY1970; print, 2021.

4. Luis Carle (American, born 1962) Sylvia Rivera (middle) with Christina Hayworth and Julia Murray, 2000Gelatin silver print 43.6×29.1 cm (173⁄16×117⁄16in.) Washington, DC, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Acquisition made possible through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center, NPG 2015.37.