The early 20th century was defined by upheaval. The two World Wars claimed millions of lives, left European cities decimated and triggered mass social reform. It was an era of change: empires believed infallible began to collapse, political ideologies like fascism and communism came to the fore, and traditional gender roles shifted in the wake of mass conscription during the wars. The art world also grappled with this rapid transformation. Artists sought to orient themselves in an increasingly disorientating world, with movements like Surrealism, Dadaism and Modernism expressing fragmented realities and subconscious experience. Ilse Bing, Kati Horna and Dora Maar were central figures in this new frontier of creation. They experimented with innovative darkroom techniques, unexpected angles and photomontage to develop a radical visual language for a new age. Now, Huxley-Parlour, London brings together these pioneering figures, reminding audiences of their vital role in shaping contemporary art.

This period saw avant-garde practitioners like Lazslo Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Rodchenko redefining what it meant to use a camera. Ilse Bing (1899-1998) was one of the foremost figures in this effort. Pathfinders presents photographs that demonstrate Bing’s ability to capture motion with clarity and precision. They include shots of dancers at the Moulin Rouge and circus performers. The images were taken throughout the 1930s, and the blur of twirling skirts are a pictorial representation of the joie de vivre that was so keenly felt in the interwar period. Other series depict fleeting urban moments taken from innovative, unexpected angles. This style was characteristic of the emerging language of “New Photography,” and helped define the visual lexicon of European Modernism. Bing was personally affected by WWII, and this is reflected in her later works. She was a German Jewish émigré and held in an internment camp in France before escaping to New York in 1941. In the USA, she experimented with night photography, taking on a more introspective tone in response to exile and displacement.

Meanwhile, Kati Horna (1912 – 2000) turned the lens of a different conflict. The Spanish Civil War raged between 1936 and 1939, fought with great ferocity on both sides and resulting in an estimated 200,000 casualties. Horna relocated to Barcelona to collaborate with antifascist networks during the period. Her images of wartime Spain offer a uniquely female perspective to a bitter war was otherwise almost solely recorded by men. Just a few years later, Horna was forced to flee Nazi persecution, moving to Mexico in 1939, where she became a central figure in a community of exiled Surrealists including Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo. The works she created there have a distinct visual language, rooted in the theatrical and uncanny. Her shots frequently feature masks and dolls, obscuring and fragmenting faces, whilst other images see bodies distorted by glass and imagined in innovative ways.

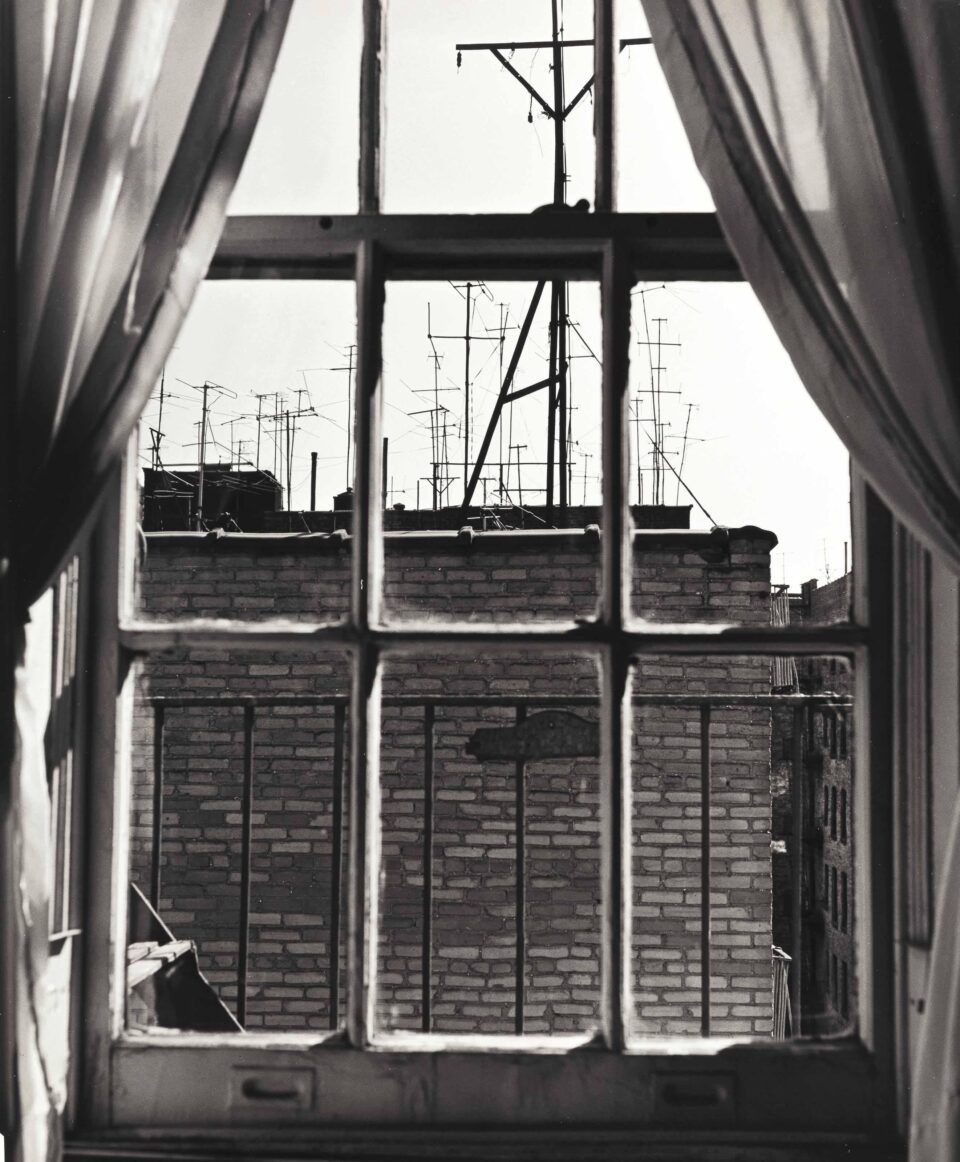

Dora Maar (1907-1997) is another name synonymous with photomontage and surrealist photography. Her image of a hand emerging from a seashell is iconic, as is the shot of a female figure in a glittering dress, her head replaced with a paper star. Yet, Maar was overlooked for much of the 20th century, overshadowed by her role as Pablo Picasso’s muse. She acted as the model for the renowned Weeping Woman, alongside several other paintings, and was in a complex relationship with the artist for nine years. More recently, she has rightfully been restored to the canon, with major exhibitions at Tate Modern, London; Pompidou Centre, Paris; and in Los Angeles. Pathfinders continues this effort, showcasing a selection of 1930s contact prints that reveal Maar’s understanding of the juxtaposition between form and surface. Her images of mannequins, deserted streets and fractured reflections offer a quiet departure from reality.

Each of these artists worked at a time when female practitioners were often disregarded or overshadowed by male counterparts. They embraced alternative perspectives and pioneered new approaches, from Surrealist inflected street photography to experimentation with photomontage, solarisation and other darkroom techniques. Yet, their legacies have beeen relegated to the depth of history and their contributions to 20th century art ignored. Their return to the spotlight is long overdue, brought with the increased call for gender equality and justice, both in the art scene and across all aspects of life. Bing, Horna and Maar’s creative trajectories echo those of countless other displaced by war and authoritarianism. Together, they forged new routes shaped by resistance, reinvention and imagination.

Pathfinders is at Huxley-Parlour, London until 13 September: huxleyparlour.com

Words: Emma Jacob

Image credits:

1. Ilse Bing, Self-Portrait with Leica Camera, Paris, 1931. Image courtesy Huxley-Parlour

2. Ilse Bing, New York, 1951. Image courtesy Huxley-Parlour.

3. Kati Horna, Untitled, Leonora Carrington from the series ‘Ode to Necrophilia’, 1962. Image courtesy Huxley-Parlour.

4. Dora Maar, Rooves [Notre-Dame and The Pantheon in the Distance], Paris, (Toits [Notre-Dame et le Panthéon au Loin], Paris), c.1935. Image courtesy Huxley-Parlour.

5. Kati Horna, Untitled, Leonora Carrington from the series ‘Ode to Necrophilia’, 1962, Pathfinders. Image courtesy Huxley-Parlour.