Artistic traditions are vital. Passed down through generations, they preserve cultural heritage, offer a window into history, and help shape both individual and collective identity. Yet they are also there to be deconstructed, critiqued and reshaped – providing a foundation upon which to build new legacies and forms of expression. Xinyue Liang explores the role of Chinese artistic traditions in a contemporary context. She brings together a range of materials and methods – from brushstrokes inspired by calligraphy to ceramics, paper, rope and quartz sand – to ask where to go next. The delicate balance between honouring the past and embracing innovation was the focus of Liang’s recent exhibition at JW Marriott’s Grosvenor House, London, where she posed the complex question: “should artists rely on tradition to create their artworks?” Aesthetica spoke to the artist about the show, what she hopes audiences will take away from her work, and what it means to create art in a globalised world.

A: Tell us about how you got started in the art world. Where did it all begin?

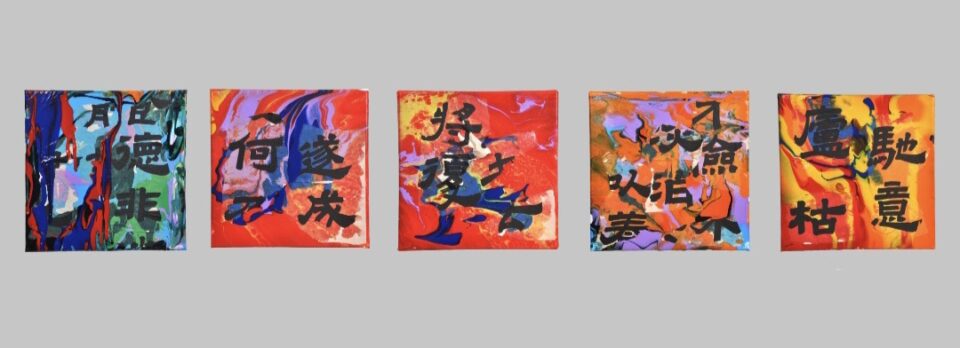

XL: My journey is deeply rooted in an early exposure to art, but the pivotal moment came during my master’s studies at the University of the Arts London (UAL) in London, from 2022 to 2023. Although I had been in contact with the arts since childhood, it was the academic environment and creative atmosphere at UAL that truly opened the door for me. There, whilst pursuing MA Fine Art Drawing, I was exposed to a diverse range of forms such as drawing, painting, sculpture and printmaking. More importantly, this period sparked my deep interest in experimenting with the integration of materials, such as combining traditional Chinese calligraphy with clay, paper and porcelain. This experience not only expanded the boundaries of my expression but also inspired me to explore the intersection of traditional and contemporary art, laying the foundation for my subsequent creative direction focused on “cultural inheritance and innovation through material fusion.”

A: Bound & Beyond is an evocative title. Can you share how this came about?

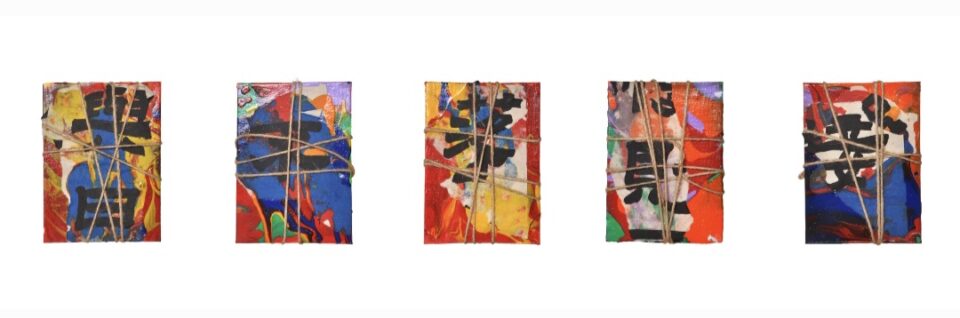

XL: The two words, “Bound” and “Beyond,” may seem contradictory. “Bound” is a term I refined from my artwork Bound Heritage, which symbolises a traditional body that is tied yet struggles to break free. It explores the duality of traditional Chinese family structures, examining the tension between control and the desire for liberation. The works focus on the structure of traditional Chinese families, highlighting the “rope-like” family bonds in Confucian ethics. These bonds embody both the warm connection of blood ties and the implicit discipline of intergenerational expectations and traditional Confucian norms. For example, in the Bound Heritage series, the text installations wrapped in linen ropes visually represent how ethical concepts like “loyalty and filial piety” invisibly constrain individual freedom, akin to “cultural heritage” tied down by ropes. My vision for this exhibition is not to seek a bound result, but rather to transcend it. To break free from being bound is to embrace the beyond – a progressive relationship. This aligns with exploring the connection between cultural heritage and innovation, as well as tradition and modernity.

A: You have said that “when Chinese artists promote traditional culture in the West, they may inadvertently reinforce stereotypes of Chinese culture as stagnant, backward or feudal.” How do you balance past and present in your work?

XL: If this were a few years ago, I would have said I honoured tradition. However, since studying in the West, and experiencing a liberal society in the UK, my perspective has subtly shifted – a so-called “awakening”. I am moving towards adopting a more neutral stance. Tradition in my work is less something to be honoured, and more something to be deconstructed. For example, in the Branch collection, I ruthlessly tore apart calligraphy works by hand. In the Fragility of Mud collection, I integrated calligraphy with clay and paper, eventually creating a new material for which I have applied for a patent. These works symbolise my resistance to and deconstruction of tradition.

A: Tradition features heavily in your aesthetics, yet you push against it conceptually. Where do you draw the line between homage and critique?

XL: This question was frequently raised by viewers during the opening of my solo exhibition. Tradition indeed plays a significant role in my aesthetic, yet I challenge it conceptually – something I refer to as a form of “gentle resistance”. It also reflects my artistic philosophy: to fight fire with fire. It is precisely this contradiction that plays a key role in creating fascination, as it evokes a sense of confusion. For me, tradition is both a language and a constraint. It offers the soil in which my work takes root, but I am never content to merely replicate what has come before. I often draw on traditional symbols, techniques, or materials – not out of nostalgia, but to reactivate their meanings in a contemporary context. I do not draw a strict line between homage and critique; more often than not, they coexist. True homage comes from deep understanding and the courage to question, while meaningful critique often arises from a profound connection to what came before.

A: From ceramics to paper, rope and quartz sand, you use a range of materials in your work. How do you choose what you work with and what roles do they play in your visual language?

XL: I choose materials based on their inherent qualities, emotional resonance, and how they relate to the themes I explore. Each material – whether it is ceramics, rope, paper, or quartz sand – carries its own texture, weight, fragility and history, which becomes part of the narrative. For example, ceramics evoke both permanence and vulnerability; rope brings in tension, connection, or even restraint; paper offers a sense of ephemerality, whilst quartz sand reminds me of time and transformation. These materials are not just media. They are collaborators in shaping the visual language and the atmosphere of the work.

A: What does being a Chinese artist today mean to you – both at home and when showing your work internationally?

XL: Should art have a nationality? If the answer is no, then I believe artists should have no nationality either. From my observation, even at the Venice Biennale, most national pavilions today focus on showcasing the individual visions and interests of the exhibiting artists, rather than conveying national meaning or embodying national identity. So, I hope that in the future, people will view artists more from the perspective of being global citizens, rather than labelling them as Chinese artists.

A: Who, or what, inspires your creative practice?

XL: I am influenced by a wide range of artists and forms, both traditional and contemporary. I am particularly inspired by creatives who push boundaries, challenge conventions, blend different materials or incorporate cultural elements into their compositions. I also find inspiration in the process of creation itself – the way new ideas emerge and evolve as I work.

A: In what ways has collaborating with curator Dr. Quan Liu influenced the final curation or interpretation of this exhibition?

XL: Dr. Quan Liu’s ability to bridge art and academia deeply fascinates me. He is both a magician of space and a philosopher. One thing he said left a lasting impression on me: “being a true curator goes beyond simply hanging paintings on walls or achieving visual and conceptual harmony within a space – it lies in one’s depth of knowledge and capacity for critical thinking.” He seeks radical and challenging artworks, and believes that they should be completely detached from tradition, both conceptually and visually. I am not entirely convinced by this, though. During the curation process, Dr. Liu aimed to create a more exaggerated display to make the concept of Bound & Beyond more explicit and overt. However, I preferred to let the artworks speak for themselves.

A: Looking ahead, what conversations or questions do you hope your art continues to provoke?

XL: I hope my art continues to explore the interplay between tradition and innovation. Considering how many Chinese artists are drawing upon Chinese tradition to create their artworks in this modern era, I hope that one day my works will inspire deeper reflections and, through the audiences’ responses, help me find an answer to the question: “What does it mean when artistic imagination is constrained to engage deeply with history and tradition, yet disengages from the present moment?”

Words: Emma Jacob & Xinyue Liang

Image credits:

All images courtesy of Xinyue Liang and Roberto Quanliu Creative Ltd.