Jyll Bradley (b. 1966) describes her art as “queering minimalism.” Her oeuvre reinvents the visual language of an iconic 20th century movement, imbuing geometric shapes with examinations of identity, urbanity, light, nature, queerness and community. It’s an approach that has led to major exhibitions at Hayward Gallery, Turner Contemporary and Walker Art Gallery, as well as inclusion in Folkstone Triennial. The latest in this list is The Box, Plymouth, where a major retrospective is on display. Running and Returning brings together Bradley’s films and sculptural installations, alongside works of historical significance for the first time. Here, audiences are invited to step into the artist’s world of light and colour. Victoria Pomery, CEO at The Box, said: “Jyll Bradley has been creating captivating work for more than three decades, with a pioneering approach and creativity that has resulted in an incredibly broad-ranging practice. Witnessing her ability to combine the highly personal with the public is a real privilege, and she shares her distinctive yet universal vision with great generosity.” Aesthetica spoke to Bradley about her illustrious career so far, how she feels about revisiting her works and what she hopes visitors will take away from the show.

A: Tell us about this exhibition. How did it come about?

JB: Victoria Pomery commissioned me to create the large outdoor installation Dutch/Light (2017), when she was the Director of Turner Contemporary. Our conversations began some years back. She felt it was an exciting moment to bring all aspects of my work together. So we hatched a plan for a survey show.

A: This exhibition marks the first time your early photographs, such as Naming Spaces and Urban Cowboys, have been displayed in over a decade. How do you see these pieces now, in the context of your more recent practice?

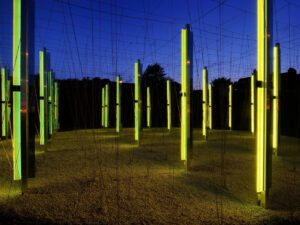

JB: These works were made at the start of a long enquiry about structures of light that has continued through to today. I came from Kent and grew up around hop gardens – human structures that are built to channel natural light for growth. When I moved to London to attend Goldsmiths in 1985, I became immersed in urban light. For many years I felt a disconnect between the rurality of my childhood and my life in the city. Then, in 2014, I made a work called Green/Light (for M.R.) for the Folkestone Triennial, which fused the natural materiality of my childhood with the LED and fluorescence of my urban self. Things have come full circle, and the early works are part of that journey. It is interesting that both then and now, I use practical “off the shelf” elements to make my light works. Previously, it was “off the shelf” lightboxes; now, Running and Returning is made with “off the shelf” garden cloche mechanisms. It is very exciting for me to show the early lightbox stuff alongside my recent pieces. That hasn’t happened before. The show is also the first time some of my very first works, made when I was a teenager, are on display. They are a sequence of watercolours and wax of the greenhouse in our garden disappearing into the night. Somehow these small works are fully formed and seem to anticipate my practice for years to come.

A: Upon entering the show, the first thing visitors will encounter is a portrait of yourself. Why did this feel like the right starting point?

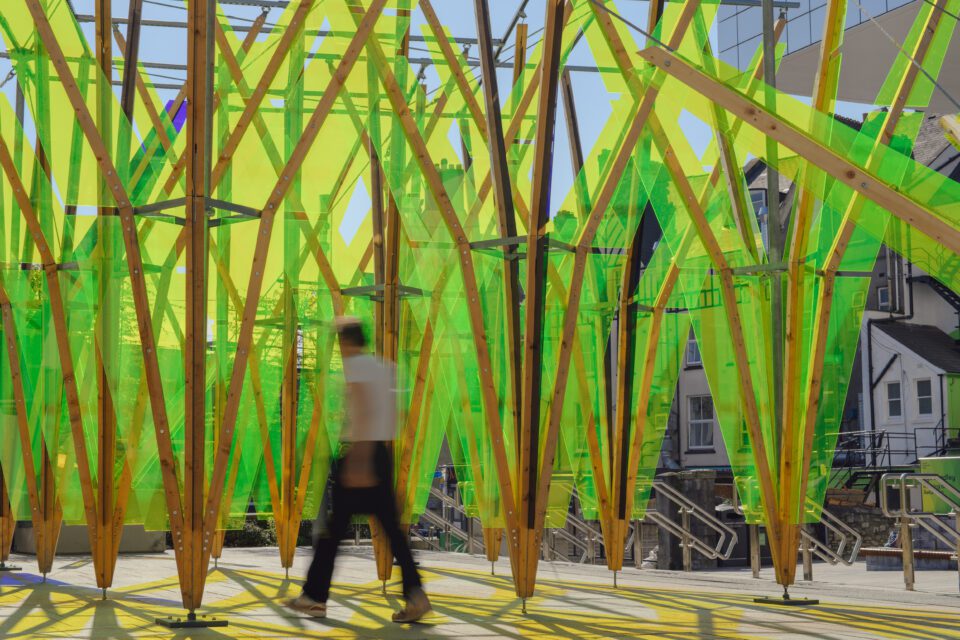

JB: I’m really interested in the idea of hospitality and art. As an artist, what is it to invite someone into your world? The first work of mine that audiences encounter in my exhibition is actually The Hop, my large-scale outdoor installation. You have to walk through The Hop to enter St Luke’s. You’re literally going from my outdoor world, the work people most associate with me, to the inner, lesser-known realm of drawings, films, photography within the gallery. The portrait I’m showing connects these two aspects. It’s an image of me aged 20, pausing in the threshold of my dilapidated family greenhouse. It was a really important place to me growing up, it’s a transparent place, yet sheltering, where I felt inside and outside at the same time; reflecting my experience as a young queer woman. The greenhouse – like The Hop which people have just walked through – is a structure designed to bring light to a place to grow things. It made sense to welcome people with this portrait. It’s an invitation to come on a journey with me that goes back nearly 40 years.

A: Light has been central to your work for 35 years. What is it about the medium that keeps drawing you back?

JB: I’m compelled by light as both medium and metaphor. That might mean a structure we build to channel light for growth or bringing a hidden story to light, as in the case of my relational project Mr Roscoe’s Garden, which was made for Liverpool’s year as European Capital of Culture 2008. I equate light with androgyny and fluidity, hence the different forms my art takes. I’m interested in what I call the “work of light”; we think of it as ubiquitous, everywhere, but it takes real human work – practical, spiritual – to harness its potential.

A: Your use of commercial lightboxes was groundbreaking in the UK art scene. How did that early decision help you articulate themes of visibility, identity and transformation?

JB: I started using them in my work at the height of debate about advertising, particularly in feminist thinking. How women were represented and objectified was hugely contested and lightboxes were formal vehicles for this toxic communication. In advertising the point of a lightbox is to amplify a commercial message, make it literally and metaphorically shine brighter. I decided to subvert this by using the lightbox to show images of my queer friends but introduce ideas of the poetic with literary text. I was attempting to make visible something less easy to categorise, label and own, something more open and against literal messaging around identity. I also introduced sculptural elements, simple white painted panels that leant beside them like empty pages. These slowed down the viewing experience and created space for the viewer. The lightbox was no longer a mere vehicle for an image but transformed into an installation and space.

A: You’ve described your practice as “queering minimalism.” How has reimagining this visual allowed you to reclaim space?

JB: For me, something very interesting happens when you step away from a very literal representation of queerness and enter a stripped back aesthetic. I start to think about facets of self and experience and how these might manifest and unite in material form. My sculpture works titled Graft exemplify this – they comprise planes of organic wood, fluorescent live-edge Plexiglas and mirror. I see them as self-portraits: they are simple, made to my height, yet multi-faceted and work with reflection and illusion. They are both practical and mysterious. Graft is also a word for hard work. I think of the hard work it takes to combine aspects of self together – minimalism takes me back to that essential question of who I am. I feel a kinship with queer artists such as Roni Horn and Felix Gonzalez Torres. There is something about creating a space for yourself that a minimalist approach offers. And space for the audience.

A: What do you hope audiences take away from Running and Returning?

JB: We’ve curated the show thematically rather than chronologically. That way visitors can visually and spatially “run and return” between different artworks and eras and open unusual conversations between them. I’ve also gone back to works from long ago and remade them, or used material created way back and brought it to the fore. I’d like people to be inspired by this, that life and creativity are not linear. There’s a beauty and strange comfort to discovering unexpected connections – the delight of finding things that were always already there. I hope people take away a sense of the wonderment of creative journeys.

A: What’s next? Anything we can look forward to?

JB: This autumn I’ll be presenting a solo booth at Independent 20th Century in New York with my gallery Pi Artworks. I’ll also be having my first solo show at Pi Artworks Istanbul space to coincide with Istanbul Biennial.

Jyll Bradley: Running and Returning is at The Box, Plymouth until 2 November: theboxplymouth.com

Words: Emma Jacob & Jyll Bradley

Image credits:

1&5. Jyll Bradley, The Hop (detail). Image Thierry Bal. Courtesy of the artist.

2. Jyll Bradley, Self-Portrait, Greenhouse, 1987. Image by Jack Bradley.

3. Jyll Bradley. The Hop. Expanded install shot. Image Thierry Bal. Courtesy of the artist.

4. Jyll Bradley, Self-Portrait, 1987-2024. Courtesy of the artist.