Labor Day is a US national holiday celebrated to honour the American labour movement. The day was signed into law in July 1894, marking the official end of the Pullman Strike. This industrial action saw 250,000 factory workers at the Pullman Palace Car Co. in Chicago, walk out in protest of 12-hour workdays and reduced wages. It is just one example of countless moments of collective resistance, that have brought about progress and developments such as the weekend, better and safer working conditions and higher wages. These demonstrations were also tied up in matters of immigration, women’s liberation, civil rights and class struggle – in a nation where 211 million people are of working age, it underpins all aspects of life. Today, the country still has no statutory entitlement to paid time off and the rise of the “gig economy”, which is short-term, flexible and freelance work, means that more than one third of the workforce no longer have traditional salaried, full-time roles. Conversations about workers’ rights are by no means over. Present-day society, shaped by convenience, wealth disparity and digital technologies, has brought its own issues for unions.

The International Centre of Photography’s latest exhibition, American Job: 1940-2011, draws upon more than 40 photographers to explore the breadth and contemporary relevance of the US Labour movement. The show features the images of Arnold Eagle and W. Eugene Smith, which engage with the trade union and strike activity of the 1940s and 1950s, whilst Cornell Capa and Robert Frank documented labour’s complicated relationship with politics and media. Bettye Lane, Freda Leinwand and Susan Meislas centre around the mass entry of women into the workforce in the 1970s. Aesthetica spoke to co-curator Makeda Best, a photographic historian, about the artists featured, why the images continue to be relevant today and what she hopes people will take away from the show.

A: American Job: 1940-2011 spans an expansive period of American history, when there were so many seismic changes. What drew you to focus on labour, activism and social change as the central themes for this exhibition?

MB: Those themes are there, but the exhibition is also bookended by war – conflict has impacted our economy, media, created cities and regions, and influenced movement and settlement in incredible ways. The exhibition marks the end of an era and beginning of the one that we are in now, with technology being a key driver. 2012 was a turning point. So, I was interested in the time before then and the photojournalism in that period.

A: Why do you think these themes continue to resonate with audiences in 2025?

MB: I think it’s because the questions still resonate – what it means to work in America; whose work is visible or valued in society and whose is not; and what rights people have in employment continue, to be fundamental questions. The issue of how those answers map onto our ideals is also something that people are still considering. I don’t think that’s a bad thing.

A: There is a constant dialogue between historical ideas and contemporary perspectives on labour. How did you weave these together in the exhibition?

MB: What’s striking are the ways the photographs reveal those connections. In images by Bettye Lane, Freda Leinwand, Sophie Rivera and Susan Mieselas, one of the threads is women’s work and how women became more visible in the workplace throughout the second half of the 20th century. The link between labour and identity is also there – you see it in the faces of the people in the photographs of Paul Schuster from the 1960s and Dylan Vitone in the 2010s. The exhibition makes connections across time and also geographies. The Poor People’s Campaign of 1968 directly echoes the 2011 photographs by Accra Shepp of Occupy Wall Street. Both used encampments as a means to draw attention to inequities.

A: The show includes works by both renowned photographers, like Gordon Parks, and lesser-known figures. How did you balance the inclusion of well-established names with those whose contributions may have been overlooked?

MB: The exhibition illustrates that that those well-known photographers weren’t working in a vacuum. There were press photographers and amateurs – there are some continuities in terms of their training, exposure, and influences, but many different visions. Visitos will see the richness of artistic expression and the ways in which the photographers they may be more familiar with worked within a professional context and broader visual culture. The exhibition is drawn from the ICP’s collection with a few supplements to finish the story. It isn’t meant to be comprehensive – but that’s also what’s interesting, it reflects decades of collecting, and I’ve tried to build a story around that.

A: It’s difficult to think about activism in the 20th century without also considering the Civil Rights Movement. Did this play a role in the curation of the show?

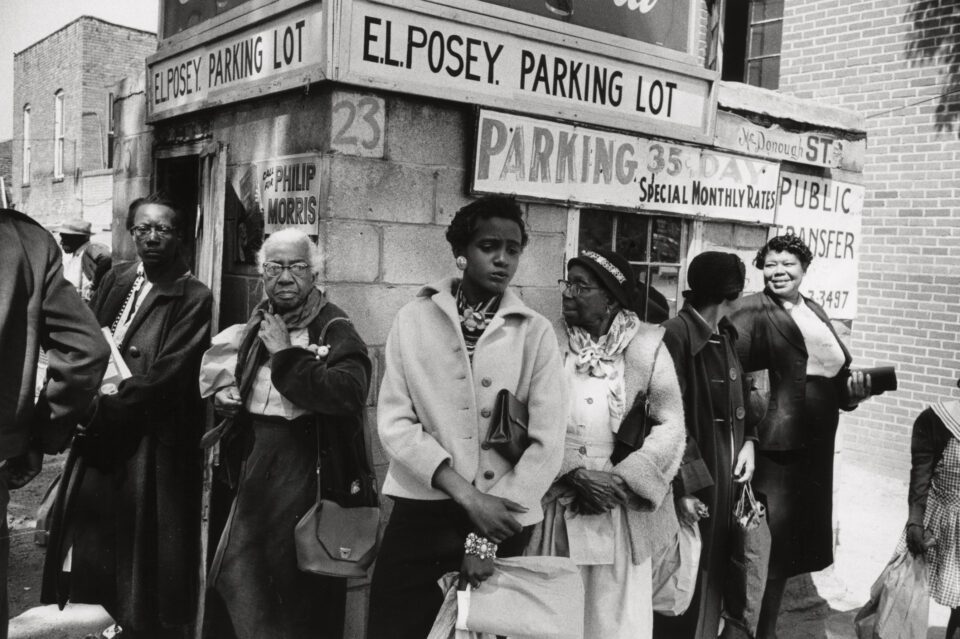

MB: I want visitors to see photographs that they may be familiar with in a new way. You can’t understand the famous “I am a man” placards the sanitation workers wore in the Ernest Withers’ 1968 photograph without understanding those words are also about people calling for dignity throughout all aspects of their lives, including how they labour. When you see the photographs related to the Montgomery Bus Boycott – that was a movement created by women who were using the bus to get to work – they were working women. There is a section is titled “Economics must be part of our struggle” which are the words of Dr Martin Luther King Jr. Many of the protests he engaged in during the last years of his life were focused on jobs and economic security and equity.

A: Do you have a personal favourite image from the collection?

MB: I find different images really moving, in Freda Leinwand’s Disc Jockey, the joy in the woman’s face is just beautiful. Ken Light’s welder with his makeshift mask is incredible – the man’s pose and the construction of the mask, but also the sense of precariousness that underlies that. I love the book by Jon Lewis on the United Farm Workers. The text is so impactful. So many pictures for different reasons!

A: What do you hope people take away from visiting the exhibition?

MB: I hope people notice the connections between the past and the present and that they learn something new about photography’s dynamic role as objects and images in our culture.

American Job: 1940 – 2011 is at International Centre of Photography until 5 May: icp.org

Words: Emma Jacob & Makeda Best

Image credits:

Cornell Capa, [John F. Kennedy supporters near Merced, California], 1960. International Center of Photography, Gift of Cornell and Edith Capa 2004 (112.2004) © International Center of Photography / Magnum Photos.

Dan Weiner,Bus boycott. Montgomery, Alabama, 1956, International Center ofPhotography,Museum Purchase, International Fund for Concerned Photography, 1974(1012.1974)© John Broderick.

Cornell Capa, [John F. Kennedy shaking hands, Michigan], 1960.International Center ofPhotography,Gift of Cornell and Edith Capa,2004(107.2004)© International Center ofPhotography / Magnum Photos.

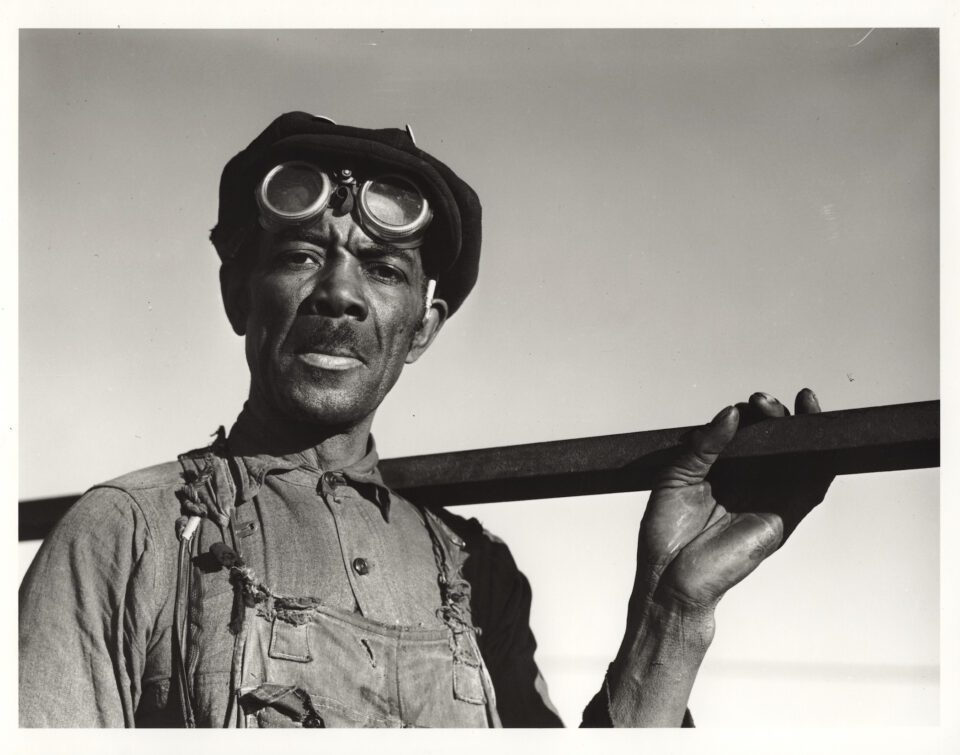

Jack Delano, Frank Williams, 1941. International Center of Photography, Museum Purchase, 2003 (82. 2003).

Freda Leinwand,Sound engineer at radio station WMCA New York, 1975.Part of the Freda Leinwand Papers, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute© Freda Leinwand.