When the first printing press was invented in the mid-15th century by Johannes Gutenberg, it was a scandal. The source of the scandal was the replacement of hand-made works with thoughtless reproductions, i.e. the cheapening of valued goods. The book was an object revered for its unique ability to communicate knowledge; so some were worried that just anybody could get a book now, shattering a solid network of social classes. And to nobody’s astonishment, the printing press realised most of the worries – it was the sole source of widely distributed texts for the first time. So it’s a wonder that after 500 years printing is still making leaps and bounds, giving rise to bombastic new abilities in expanded fields. Wade Guyton’s mid-career retrospective, Wade Guyton OS – currently mounted at the Whitney Museum, is momentous both for Guyton and for the next generation of artists who wish never to pick up the brush. Filled with attractive, sizeable stretched linen that has been printed upon, as well as small book sized images, almost everything in the exhibition was created using large format inkjet printers (with the exception of a few chair sculptures, and a sculpture consisting of a woodpile that reeked of afterthought). The show is, ceteris paribus, a solid accomplishment – a glimpse of the possibilities wherein digital media and manual labor synaptically combine, laden with both traditional formal properties and new technological channels.

The majority of the show comprises of his well-known minimal printed works. They are large primed canvases that are decorated with a serious of slight gestures – pithy contemplations of one element. There may be Us, Xs, circles, or stripes, printed in a brusque palette of colors; masses of black, with bits of reds, blues, greens, and yellows. Using programs like Microsoft Word in combination with his flatbed scanner, Guyton creates parsimonious arrangements and rearrangements of computer generated imagery. Through the use of repetition, the strengths of the work start to become apparent, as each slight change from canvas to canvas seems to incur a change in discursive thinking about decisions. The layout of the show within the Whitney’s third floor gallery is also a thoughtful decision. Large canvases are hung on thickly layered temporary walls that one may pass through in whatever order seems best – no specific entry or exit – denoting the density of the work. Almost everything in the exhibition rides the fine line between austerity and playfulness. Heaping segments of blackness are offset by images of flames sourced from mass-produced magazines or books. Designs that flirt with modernist tropes are positioned with either care or carelessness upon magazine and book pages that contain some of the same tropes that they are contending with.

In the rear of the gallery are two works, the largest in this show, which are both comprised of long green and red stripes. They engage the viewer in a sense of the sublime, echoing the concerns of Barnett Newman; but once it becomes known that the basis of these works is from a page of a book that he ripped out, they recoil into the frivolous. Why would anyone enlarge such an insignificant portion of a book (which probably was not that important to begin with) to such a spectacular size? Maybe the critique at play here is that these physical tropes of modernism that he employs have kernels throughout the cultural sphere; deeply penetrating the very foundation where one did not know could even be modern. A simply end page in a book would never have been described as an important feat of modernism. Guyton acts as a clairvoyant in the inspired selection of humdrum details that go unnoticed for most people.

Labor itself is frequently one of the components of Guyton’s work. This is conveyed in the way that he battles each piece. He might drag freshly printed linen across the studio floor, leaving marks and scuffs across its surface. He welcomes printer jams and ink splatters, alluding to the literal tug of war that one may have with the printer. And though he is not going to get physical with his works in the way Brancusi might have done, he is still going to exert himself hoping to achieve the same result. Maybe Brancusi might be an appropriate cultural mirror for Guyton after all: the visual elegance, the mystery and proliferation of an unexplored style, and the nuanced gradation from piece to piece, showing both progress and a return to the foundation of the medium, simultaneously. Except that the medium, for Guyton, is an inkjet printer. This serious suggestion has an almost farcical tone to it as well. In all likelihood, Gutenberg never would have thought that his printer would evolve into an embraced art medium, since it was the first instance of reproduction to disseminate and replace the handmade object. But Gutenberg would certainly be proud of Guyton’s spirit in his appropriation of the printer for these smartly executed works.

Wade Guyton OS, Until 13 January 2013, Whitney Museum of American Art, 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street, New York, NY 10021.

Nickolas Calabrese

Credits

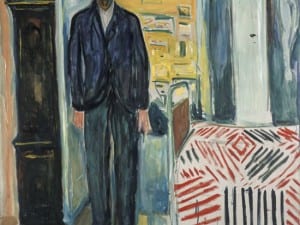

1. Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2006. Epson UltraChrome inkjet on linen; 89 x 54 in. (226.1 x 137.2 cm). Private collection. ©Wade Guyton. Photograph by Lamay Photo.

2. Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2006. Epson UltraChrome inkjet on linen; 89 x 54 in. (226.1 x 137.2 cm). The Rachofsky Collection. ©Wade Guyton. Photograph by Lamay Photo.