Is technology changing the way we see ourselves? This key question is at the heart of Virtual Beauty, Somerset House’s 2025 summer show. It brings together over 20 international artists across sculpture, photography, installation and video, sparking conversations around gender, sexuality, ethnicity and identity in the post-internet era. This is a topical and timely display, opening at a moment when debates on AI, social media regulation and the impact of screen time are everywhere. “We live in a world where digital self-curation is part of everyday life, and digitally native generations are coming of age,” say curators Gonzalo Herrero Delicado, Mathilde Friis and Bunny Kinney. “This exhibition highlights how questions of beauty are intrinsically linked to the screens and devices through which we view ourselves every day, and the altered, enhanced, or filtered identities we share via these devices. Virtual Beauty reconsiders who holds the power to define conventions of beauty today and the very definition of human identity.”

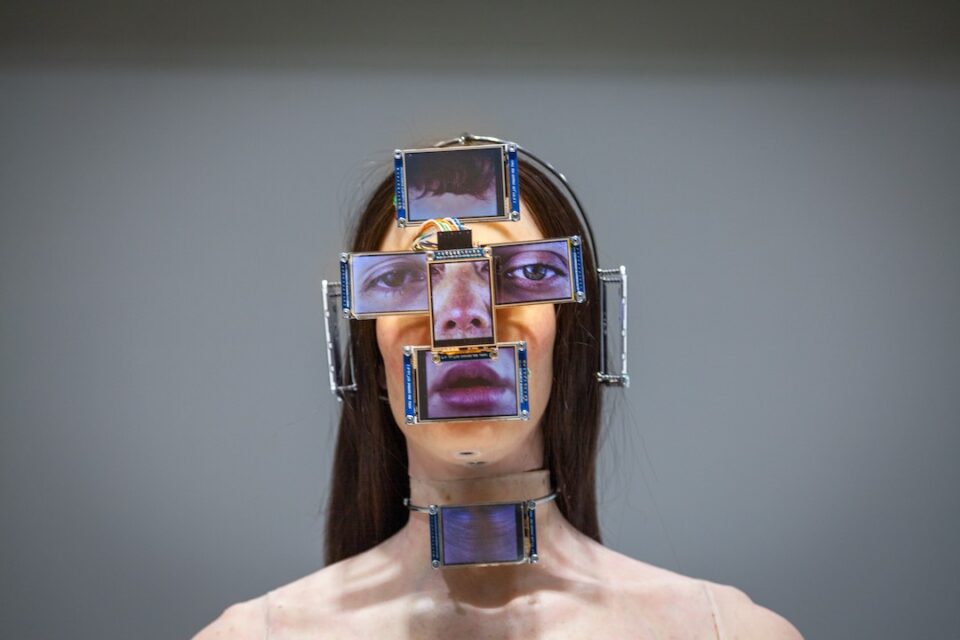

The exhibition starts off by looking back. Long before Instagram and TikTok, in 1993, ORLAN live-streamed her facial aesthetic surgery to challenge western beauty ideals. Today, at Somerset House, the piece sparks an interesting dialogue with pi(x)el (2022) by Spanish-Croatian multidisciplinary artist Filip Ćustić. This hyper-realistic silicone body has its mouth, eyes and other sensitive areas covered in LED screens. They display looped footage of assorted human features drawn from a diverse range of bodies. With a simple swipe, visitors can swap the images and construct a hybrid body beyond the conventions of gender, age or race. The work connects with Korean artist Hyungkoo Lee’s Altering Facial Features with WH5 (2010), a distorted human portrait that also plays with perception. Throughout the show, critique is paired with fun and creativity. Ines Alpha’s interactive installation, I’d rather be a cyborg (2024), delves into the concept of ‘virtual makeup’ and AR adornments – showing the imaginative potential of digital tools.

“Authenticity” is a word that often appears in discussions around social media. In 2014, Amalia Ulman’s iconic Excellences & Perfections series, now exhibited in Virtual Beauty, unfolded on Instagram. At the time, her followers didn’t know it was an artwork. Ulman had skilfully – and controversially – crafted a believable persona, through images and captions, holding up a mirror to the way women are represented and treated online. Ten years on, and generative AI is rife with similar problems – from ethical concerns to inaccurate or fabricated information. Virtual Beauty tackles this head-on. In Blonde Braids Study II (2023), Minnie Atairu offers a critical approach to the portrayal of Black identity and bias in AI-generated imagery. The project emerged after she asked: “Can the text-to-image algorithm Midjourney (V4) effectively generate studio portraits of “blue-black” or “plum-black” complexioned twins sporting blonde braids?” The results proved, worryingly, symptomatic of real-world discrimination. Elsewhere, Ben Cullen Williams and Isamaya Ffrench harness machine learning and generative software to create altered portraits, raising questions about artificial intelligence’s perception of what, or more importantly who, is considered “beautiful.”

This is just a snapshot of Virtual Beauty. As Somerset House marks its 25th anniversary, this show cements the gallery as “a home for cultural innovators.” It foregrounds creatives who want us to stop scrolling, look up from our screens and re-evaluate our relationship with technology. They urge us to ask: how is social media making us feel? Are we represented? And how do we build a better, more inclusive digital world?

Virtual Beauty is at Somerset House, London, until 28 September.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits:

1. Minne Atairu. Blonde Braids Study II (2023). Courtesy of the artist.

2. Ines Alpha. I’d rather be a cyborg (2024). Photograph by Li Roda-Gil. Courtesy of the artist.

3. Hyungkoo Lee. Altering Facial Features with WH5 (2010). Courtesy of the artist.

4. Filip Custic, pi(x)el (2022). © Filip Custic. Courtesy Onkaos.