The National Gallery of Canada presents Camera and the City, a show that brings together artists who have captured the spirit, rhythm and constant transformation of city streets. “The exhibition takes us on a tour around the world and transports us through many decades of city life while leaving a lasting impression,” says Jean-François Bélisle, Director of the Gallery. The line-up features 180 works by 106 artists, including Canadian practitioners like Raymonde April, Ted Grant, Fred Herzog and Cheryl Sourkes, and international photographers such as Kwame Brathwaite, Leon Levinstein and Lisette Model. Together, they present modern cities as dynamic public spaces of activism, community, cultural expression and protest.

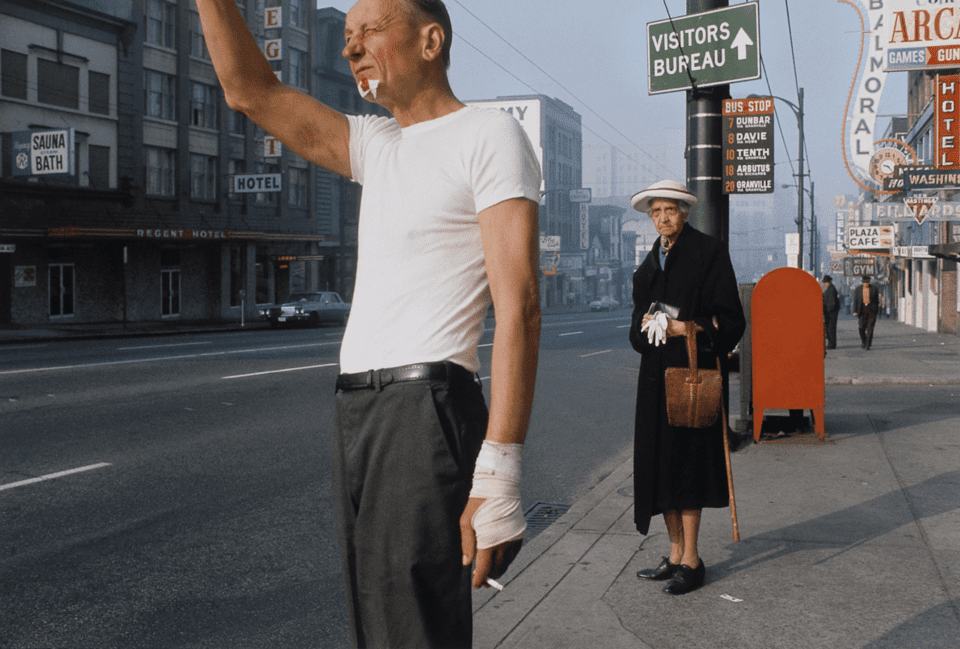

Visitors traverse three separate sections: Movement, Idea and Community. City as Movement captures the energy of urban life. Think images of crowds, vehicles, lights and reflections. Some catch the blur and speed of the city; others focus on sharp, decisive moments of everyday life. Fred Herzog’s Man with Bandage is a prime example. The 1968 photograph depicts a man with a bloodied dressing on his chin and a cigarette grasped in his bandaged hand. His general state of dishevelment is juxtaposed by an elderly woman, neatly dressed in a winter coat, hat and gloves, who looks on disapprovingly. Similarly, artists like Leon Levinstein and Lisette Model seize on fleeting gestures, highlighting how cities are constantly evolving and shifting. Levinstein’s shots have a raw, untamed energy. He would, as Kirsti Svenning wrote for the International Centre of Photography, “photograph strangers at close range, capturing the back alleys of New York City, which framed the faces, poses and movement of fellow city dwellers: couples, kids, beggars, prostitutes, families, society ladies and sunbathers.” Lisette Model continues this with images that emphasize the peculiarities of average people, offering an honest, irreverent and absurd perspective on everyday life.

Meanwhile, the exhibition’s Ideas section positions the city not just as a physical environment but as a conceptual space: a blank canvas upon which forces like corporations, consumer culture, architecture and media all leave their mark. Canadian artist Cheryl Sourkes is best-known for work involving the Internet, data, technology and surveillance. The series Net Work (2017) considers how mobile devices have changed the way society interacts with our surroundings. The artist describes how phones transform users “into an order of cyborg … divulging preoccupations, predilections, finances, movements, politics and more.” Each image shows a person as though they are glitching, reflecting how the digital world disconnects people from reality. Photographers such as Raymonde April take this even further, treating the city as a site of introspection. Her images blur documentary and concept, suggesting that urban spaces are shaped as much by memory, perception and personal narrative as by concrete streets or architecture.

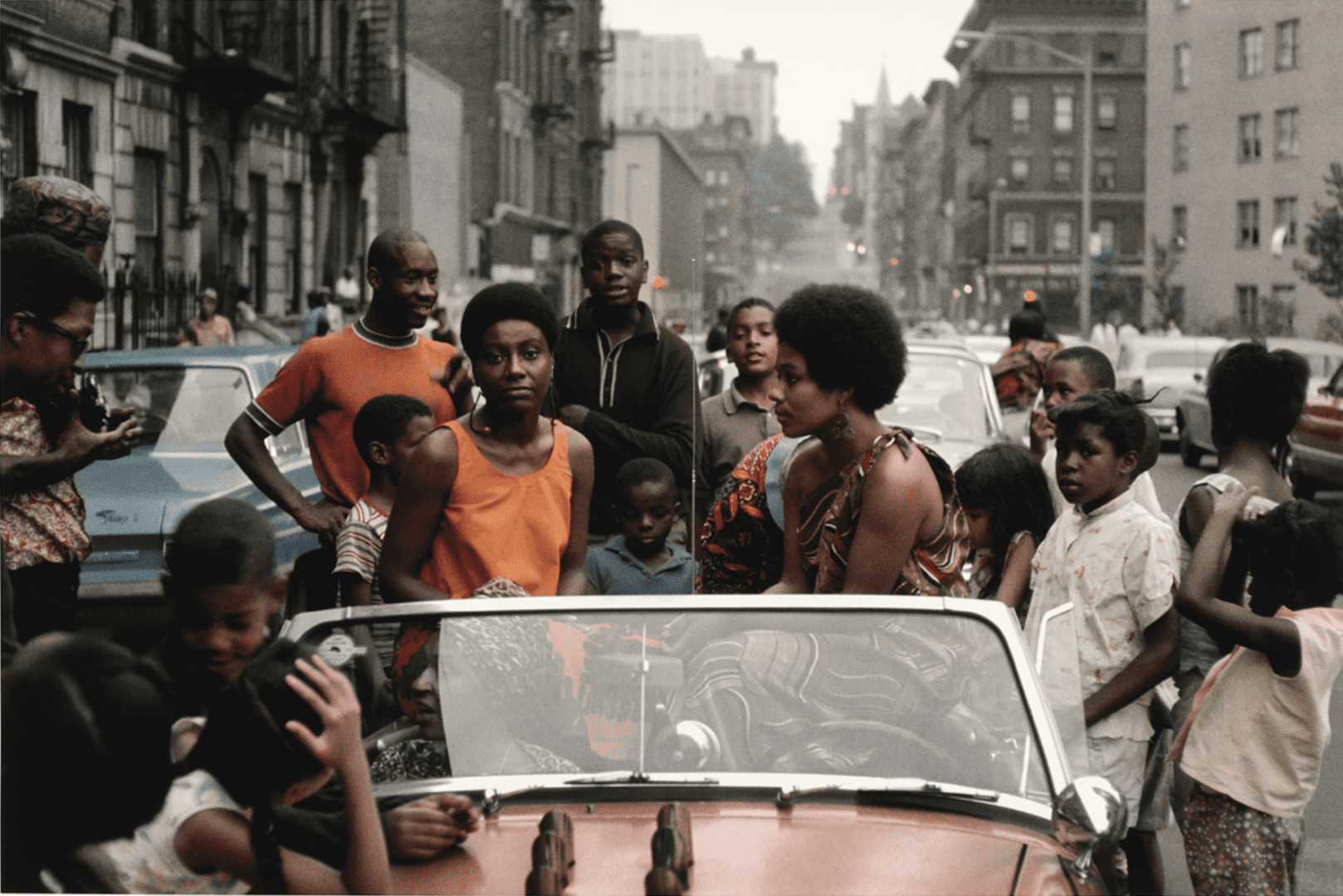

Ideas reveals the city to be shaped by constructed systems, but the final section, Community, shows it to be a place made of activism, gatherings, identities and relationships. Here, the streets are defined by the people who live there. It’s the most powerful part of the show, a testament to how places are shaped by collective action. Kwame Brathwaite, the photojournalist known for popularising the phrase “Black is Beautiful,” celebrated the self-determination and creativity of Black communities. Camera and the City features his image Untitled (Garvey Day, Deedee in Car) (1965). In it, a group of people sit in a convertible car, taking part in celebrations to honour Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican political leader and Pan-Africanist. In one instant, Brathwaite captures activism, cultural pride and community empowerment. They are themes echoed by Ted Grant, widely regarded as the father of Canadian photojournalism. His shot of a group of young men driving down the road in Vancouver’s Chinatown has a similar feeling of joyful abandon.

Camera and the City reminds us that urban life is never static. It shifts with every passerby, every protest, every moment of celebration. The exhibition brings together decades of photographs, taken from so many perspectives and in so many locations, and the result is a comprehensive and thoughtful representation of what it means to live in a city. The National Gallery of Canada offers a timely reminder of how a city’s character is made by the people who live there, and each street carries stories of collective joy, activism, pride and protest. There is never a dull moment if we take the time to truly look around us.

Camera in the City is at the National Gallery of Canada until 15 March: gallery.ca

Words: Emma Jacob

Image Credits:

1. Kwame Brathwaite, Untitled (Garvey Day, Deedee in Car), c. 1965, printed 2021. Inkjet print, 55.9 × 81.3 cm. Courtesy of the Kwame Brathwaite Archive and Jenkins Johnson Gallery. © The Kwame Brathwaite Archive, all rights reserved.

2. Ted Grant, Chinatown, Vancouver, British Columbia, May 1963, printed 1986. Gelatin silver print, 27.9 × 35.5 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. CMCP Collection. Purchased 1963. © Estate of Ted Grant.

3. Fred Herzog, Man with Bandage, 1968, printed 2009. Inkjet print, 70.9 × 96.3 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Purchased 2010. © Estate of Fred Herzog.

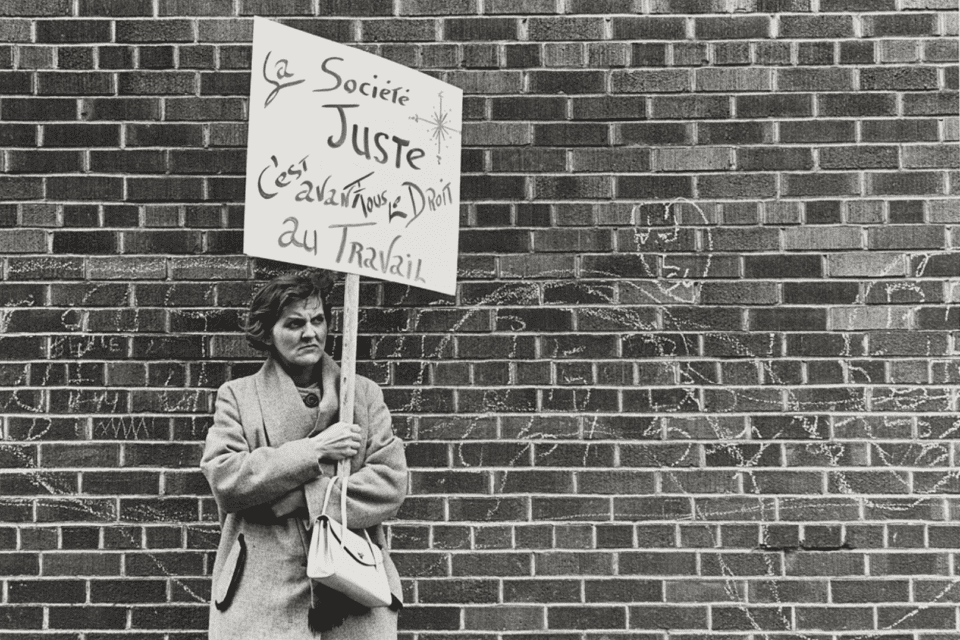

4. Pierre Gaudard, Demonstration of the Unemployed in East Montreal, Quebec, 1969. Gelatin silver print, 27.7 × 35.4 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. CMCP Collection. Purchased 1971. © Estate of Pierre Gaudard.

5. Raymonde April, Dress, 2010. Chromogenic print, 99 × 123 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Gift of Robert-Jean Chénier, Westmount, Quebec, 2017. © Raymonde April.