Few contemporary artists have shaped British art as profoundly as Tracey Emin. Born in London in 1963 and now dividing her time between Margate and France, Emin has spent nearly 40 years transforming the confessional into the monumental, the personal into the universal. From her earliest destroyed art-school paintings to her recent large-scale bronzes, her work is a fearless negotiation between vulnerability and audacity. “I feel this show, titled A Second Life, will be a benchmark for me. A moment in my life when I look back and go forward. A true celebration of living,” Emin says, and Tate Modern’s largest survey of her work promises to be precisely that: a celebration of survival, passion and reinvention.

Emerging in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Young British Artists (YBAs) were a radical force in contemporary art, known for their shock tactics, conceptual audacity, and entrepreneurial approach to exhibitions. Artists such as Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Marcus Harvey disrupted established norms, embracing materials and subject matter that blurred the lines between high art and life itself. They were fearless and unapologetically provocative – a generation that transformed the perception of British art.

Tracey Emin, however, carved out her own singular path within this cohort. While her contemporaries often engaged in spectacle and irony, Emin brought a deeply personal, confessional lens to the movement. Her work, suffused with autobiography, vulnerability and emotional intensity, expanded the YBAs’ conversation beyond provocation to the radical potential of intimate storytelling. As she herself has said, “I’ve always made work that’s honest about who I am, what I feel, and what I’ve been through.” In doing so, Emin redefined the parameters of contemporary art: she made the personal universal, showing that raw emotion, memory and the body could be as revolutionary as any conceptual gesture.

Tracey Emin’s influence extends far beyond her own generation. Artists such as Sophie Ryder, Chantal Joffe and Catherine Opie have drawn inspiration from her fearless autobiographical approach, exploring the intersections of body, identity and emotional vulnerability in their own work. Ryder’s sculptural forms echo Emin’s uncompromising physicality, while Joffe’s portraits often carry a confessional intimacy reminiscent of Emin’s raw narrative voice. Opie’s photography similarly engages with personal and communal identity, showing how Emin’s insistence on honesty and emotional authenticity has reshaped contemporary art practices across continents. Emin has not only redefined what it means to present the self in art but also opened pathways for others to confront memory, trauma and desire with equal candour.

Emin rose to prominence alongside the YBAs, a cohort defined by boldness, provocation and irreverence. Yet even within this movement, her voice was unmistakable. Her art combined the rawness of lived experience with a poetic approach that challenged the definition of contemporary art. “I’ve always made work that’s honest about who I am, what I feel, and what I’ve been through,” she reflects, a statement that resonates throughout A Second Life. Works such as My Bed (1998), her Turner Prize-nominated installation, cemented her place in the art world, combining personal trauma and rigorous conceptual framing.

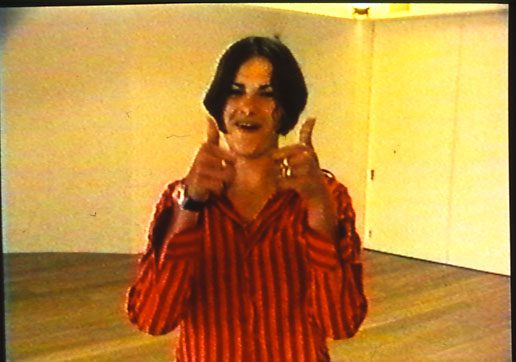

The exhibition traces Emin’s journey across media and decades, presenting over 90 works that reveal the full spectrum of her practice. Early pieces like Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995), a video recounting her traumatic teenage years in Margate, demonstrate the origins of her confessional voice. Visitors will also encounter Tracey Emin CV 1995, a first-person account of her life up until that moment, and tiny photographs of destroyed 1980s paintings from her first White Cube solo exhibition, reminding us that her art has always been inseparable from survival. “It’s about being brave enough to tell your story, even when it’s painful,” she notes, a mantra that underpins the exhibition.

Margate remains central to Emin’s narrative, a place of formative joy, turbulence and return. Following her mother’s passing in 2016 and her recovery from cancer in 2020, Emin made Margate her permanent home and founded the Tracey Emin Artist Residency. Works such as Mad Tracey From Margate: Everybody’s Been There (1997) and the wooden rollercoaster It’s Not the Way I Want to Die (2005) illustrate how the seaside town shapes both memory and imagination. “Margate has been a place where I confront my past and reinvent my present,” Emin explains, a perspective visible throughout the exhibition.

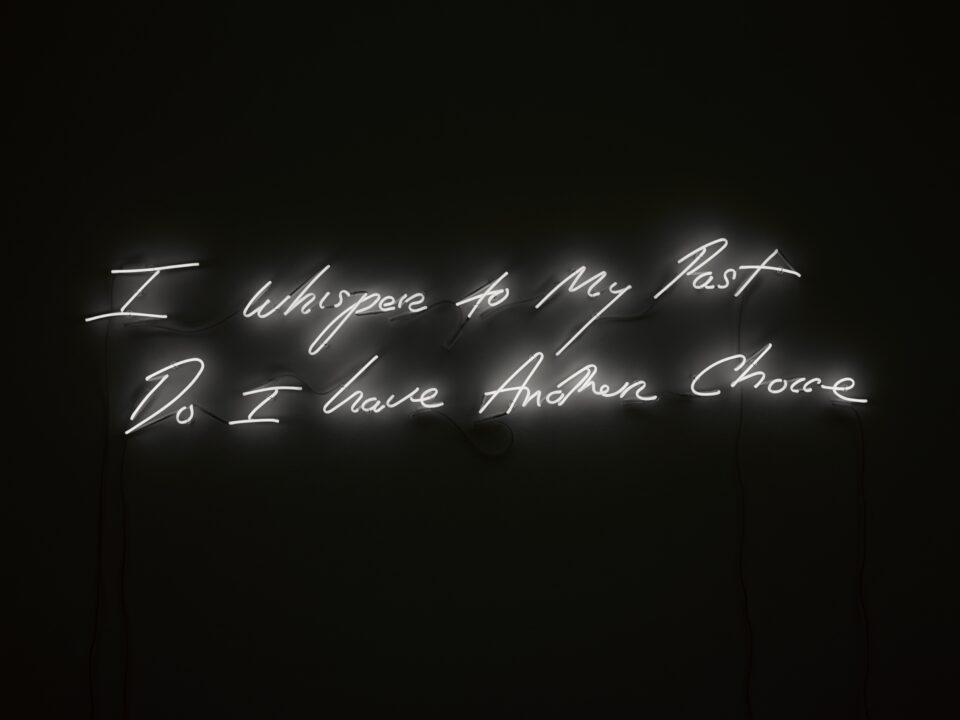

Emin’s art has never shied from confronting trauma. Neon works like I could have Loved my Innocence (2007) and embroidered textiles such as Is This a Joke (2009) address sexual assault with unflinching honesty. Her quilt The Last of the Gold (2002), emblazoned with an A-to-Z guide on abortion, underscores her commitment to public dialogue on private pain. As she observes, “If I can give someone else courage through my experience, then that is enough.”

Central to the exhibition are two installations: Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996) and My Bed (1998). The former documents a three-week period of isolation in Stockholm, a confrontation with painting after years of absence, while the latter records recovery from an alcohol-fuelled breakdown. “The works are about facing yourself,” Emin states. “You can’t hide from your life in art – you have to live it.”

The artist’s recent work continues to merge bodily transformation with conceptual rigour. Following surgery and a cancer diagnosis, Emin has created monumental bronzes such as Ascension (2024), exploring a new relationship with her body. A documentary premiering at Tate includes intimate stills of her stoma, highlighting her refusal to separate the personal from the public. “I want people to see that survival can be beautiful,” she says, a sentiment that permeates the exhibition.

The final galleries reveal Emin’s “second life” in painting and sculpture. Large-scale canvases radiate a transcendent spirituality, while bronze I Followed You Until the End (2023) dominates the landscape outside Tate Modern. Amidst these works sits Death Mask (2002), a reminder of mortality’s constant presence. “Even in darkness, there’s resilience,” Emin reflects. “I paint and I sculpt to stay alive in the moment.”

A Second Life is more than a retrospective – it is the show of the autumn, a powerful articulation of an artist who has continually redefined the boundaries of contemporary practice. “Tate Modern is one of the greatest international contemporary art museums in the world, and it’s here in London,” Emin says. “For me, this exhibition is a true celebration of living and making.” Over 40 years, Emin has changed not just what art can depict, but how it can feel. She has taken personal narrative and transformed it into a communal, visceral experience, leaving an indelible mark on contemporary art.

Tate Modern’s presentation of Emin’s work, in close collaboration with the artist, is a rare opportunity to witness the evolution of a confessional practice that spans painting, sculpture, neon, textiles, and video. “Art has always been my way of surviving,” she concludes. “And this show is a way of thriving.”

Tracey Emin: A Second Life is at Tate Modern, London from 26 February – 30 August 2026: Tate.org.uk

Words: Shirley Stevenson

Image Credits:

1&7. Tracey Emin, I whisper to My Past Do I have Another Choice2010 © Tracey Emin.

2. Tracey Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer1995 © Tracey Emin (a-e)

3. Tracey Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer1995 © Tracey Emin (a-e)

4. Tracey Emin, My Bed 1998 © Tracey Emin. Photo credit: Courtesy The Saatchi Gallery, London / Photograph by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

5. Tracey Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer1995 © Tracey Emin (a-e)

6. Tracey Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer1995 © Tracey Emin (a-e).