Rising from the former industrial terrain of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, V&A East announces itself not simply as a new museum but as a recalibration of what a national institution can be. Its architecture is assertive yet deliberately open, signalling permeability rather than authority. Developed in dialogue with East London’s long and complex creative histories, it resists the monumentality traditionally associated with museum culture. Instead, it positions itself as a civic space shaped by collaboration, access and contemporary relevance. Culture here is understood as active rather than archived. From its outset, V&A East proposes a future-facing institutional model grounded in lived experience.

This approach situates V&A East within a broader international shift in museum practice. In Rotterdam, the Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen has transformed the idea of museum storage by making its collections publicly accessible. Visitors encounter artworks through glass-fronted storage, conservation studios and logistical systems, dismantling the boundary between display and archive. The institution foregrounds process, stewardship and visibility rather than singular narratives. Similarly, the Nederlands Fotomuseum, in its current iteration, has repositioned its archive as a public-facing and discursive resource.

V&A East adopts this philosophy through both its museum and the adjacent Storehouse, which opened in 2025. Across the two sites, the institution offers unprecedented public-facing access to collections and archives, alongside insight into the mechanisms of preservation itself. This openness is not only architectural but conceptual, inviting audiences to consider how histories are assembled and whose voices are prioritised. The museum positions itself as a platform for dialogue between objects, makers and communities. Curatorial practice is aligned with contemporary cultural production rather than distanced from it. The result is a space where histories remain provisional and responsive.

It is within this context that The Music is Black: A British Story opens as V&A East’s inaugural exhibition. The decision is both deliberate and assured, foregrounding Black British music as a central force in shaping modern Britain. Rather than treating music as a supplementary cultural form, the exhibition presents it as a primary social language. Sound is explored as a carrier of memory, resistance and joy across generations. The exhibition asserts that Black British music is not peripheral but foundational.

Spanning more than 125 years, the exhibition unfolds across four acts that move fluidly between past, present and future. It begins with African musical lineages shaped by enslavement and colonialism, before tracing their transformation within Britain’s social and political landscape. The structure resists linear progression, allowing for overlaps and resonances between eras. Genres including lovers rock, Brit funk, jungle and grime are framed as responses to specific conditions. These sounds emerge through migration, technology and urban experience. The exhibition’s rhythm mirrors the complexity of the music it explores.

Material culture anchors the exhibition with both density and precision. Over 200 objects range from Winifred Atwell’s piano and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s batons to Joan Armatrading’s childhood guitar and Jme’s Super Nintendo used for early music-making experiments. Fashion, photography and personal artefacts are placed alongside immersive sound and moving image installations. Newly commissioned artworks extend the exhibition beyond documentation into contemporary artistic response. The curatorial emphasis privileges emotional engagement alongside social and historical context.

The exhibition’s significance lies not only in what it includes but in how it reframes authorship and influence. By foregrounding producers, DJs, photographers and designers, it challenges the myth of the solitary musical figure. Black British music is presented as collective labour shaped by communities, infrastructures and informal networks. This emphasis disrupts narratives that isolate success from its social conditions. It also insists on recognising forms of cultural labour that have often remained invisible.

This focus resonates with a wider global moment in exhibition-making. At MoMA in New York, Africa Photography 1900–Now reframs how African visual histories are contextualised and interpreted. In the UK, exhibitions such as Soul of a Nation, The New Black Vanguard and Black Power: Power of the People have similarly centred Black culture within major institutions. Together, these projects signal a shift away from marginalisation towards structural recognition. Yet The Music is Black distinguishes itself through its specificity and sustained depth. It insists on Britain as a site of innovation rather than imitation.

Crucially, The Music is Black: A British Story avoids nostalgia while remaining attentive to legacy. Contemporary artists and newly commissioned works sit alongside historical artefacts without hierarchy. Partnerships with BBC Music and the wider festival programme extend the exhibition beyond the gallery space. This reinforces the idea of the museum as a living platform rather than a fixed endpoint. There is a measured confidence to the curatorial approach, grounded in research and openness. We approach this exhibition with informed anticipation, recognising its potential to meaningfully reframe British history.

The Music is Black: A British Story is at V&A East Museum, London from 18 April: vam.ac.uk

Words: Anna Müller

Image Credits:

1. Jennie Baptiste, Sepia Butterfly, London, 1993 © Photo by Jennie Baptiste.

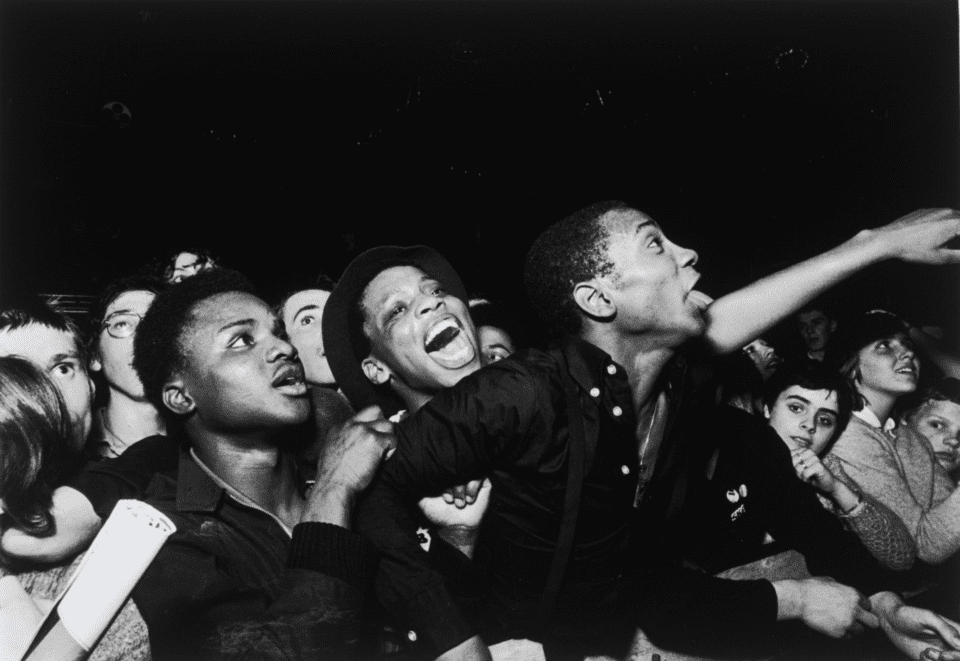

2. Syd Shelton, ‘Against Racism during The Specials’ set, Potternewton Park, Leeds, 1981 Gelatin silver print, printed 2012 © Photo by Syd Shelton.

3. Lawrence Watson, Caron Wheeler, 1989 © Photo by Lawrence Watson.

4. Tim Barrow, Janet Kay, unrecorded date © Photo by Tim Barrow, urbanimage.tv.

5. Sam White, Skepta and Jammer, Run the Road, Fabric, 2005 © Photo by Sam White

V&A East Museum.

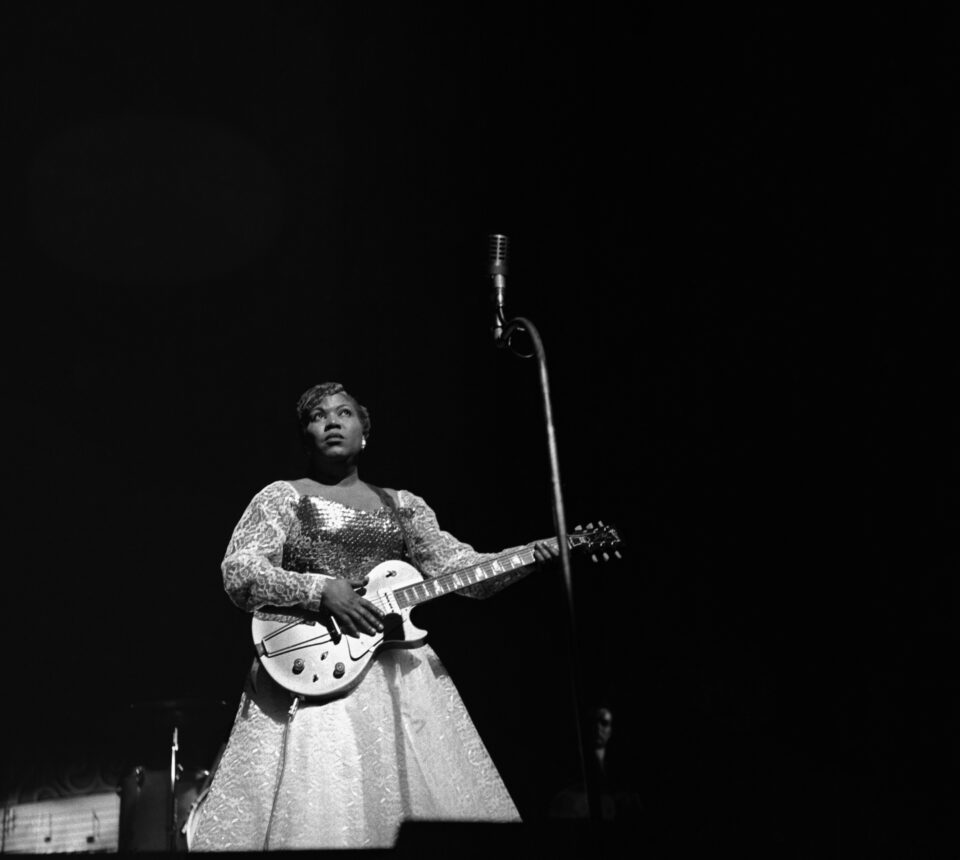

6. Harry Hammond, Sister Rosetta Tharpe performing at Drury Lane Theatre, 1959 © Photo by Harry Hammond.