Hawk Alfredson is a New York-based artist born in Sweden. He has worked exclusively in oil for 40 years, exhibiting in galleries and museums internationally. We talk to the painter about his life and practice.

A: Why do you think surrealism is still important in the 21st century?

HA: When we consider that this century began with the epic surreal vision of 9/11 broadcast in real time around the world, we must acknowledge that we live in a new reality unlike that of our recent ancestors. To hear children describe the world today one would think they were describing a Hieronymus Bosch painting.

Surreal imagery is all around us, like the air we breathe, but we often don’t notice it or see it as surreal. This imagery is like a mirror held up to ourselves as our unconscious has now broken open and we are encouraged by the media and other sources to contemplate our innermost fears and desires daily, without the harsh societal judgement of what was once repressed a century ago.

As we all move further and further away from the quaint and pastoral, surreal imagery has become commonplace. Everything is moving at an accelerated pace. Everything is felt different when the world advances faster than we can understand it. The human experience for the 21st century will have surreal experiences at its foundation; further advances in virtual reality, quantum mechanics, biotech engineering and space exploration will express themselves in the contemporary art of the future. I can only see the chaotic and surreal patterns of modern life multiplying. The visual language of surrealism will continue to evolve throughout the 21st century, becoming further manipulated as it is creatively utilised.

A: What do you hope to achieve with your paintings?

HA: What I am hoping to achieve when I paint is a sense of mystery and beauty – I wish to create a vision that not even I, the creator, fully understand.

I usually describe my imagery as “Magic Realism”. I wish to draw the viewer into an altered state of consciousness where they may be inclined to experience who they truly are in a timeless state of mind. While living in the Hotel Chelsea from 2001 to 2010, there were times when hotel guests contacted me after studying my paintings there. Some experienced deep connections to my work that made them feel “connected” to a more meaningful existence.

A: Speaking of connections, you have collaborated with Swedish author Hector Gramme on two books over the past five years, and you have created several commissioned paintings for an upcoming film based loosely on the Edgar Allan Poe classic The Tell-Tale Heart. Do you enjoy working with other artists?

HA: I welcome working with other talented artists and the results are often unexpected.

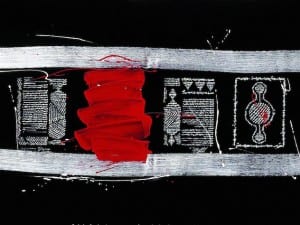

Hector Gramme is a gifted writer who I’ve known and collaborated with since 1988. He came up with the idea of a book of typewriter art created specifically for the book Into Metal Topless. I drew directly onto the images he produced with five different typewriter models. There were no rules: it was a kind of stream-of-consciousness experiment.

The other recent book with Gramme, Players of Strange, Meaningless Games, pairs his whimsical, absurd observations with 70 of my paintings.

The Tell-Tale Heart project is with musician Brannon Hungness. Brannon is a multitalented guy whom I’ve known since 1995 and in the past years he has become increasingly involved in film while continuing to make music. He has worked with Tony Levin (of King Crimson) as well as the Glenn Branca Ensemble. I’m excited about how the film is going although I don’t know too much about how all the pieces fit together. It will include about 30 of my oil paintings, some of which were created specifically for the film. I also have been given a small part as a “Dream Ambassador”, which is a sort of apparition.

A: What is your collaborative relationship with your wife, the photographer Mia Hanson?

HA: My wife has documented all my paintings on film over the last 20 years. She also inventories and manages my original works.

She has included me in her personal photographic work as well. A week after we first met, she bleached my eyebrows white and turned me into a Nosferatu-looking figure with skilled makeup techniques for a couple of dreamy, ethereal portraits. A year after that, she was working with a large-format analogue camera. No makeup involved, but extreme patience required. The photo shoot began in the afternoon and didn’t end till several hours into the next day. In general, we inspire, criticise and help each other to do better. Even after all these years!

A: You have a legion of passionate admirers of your work. What are your thoughts on the relationship between the artist and the viewer?

HA: Images and ideas enter my mind night and day, and I often feel compelled to express them as soon as they come. When I begin a painting, I usually have no definitive destination but try to just go with the flow.

Since I rarely predetermine anything in my work, I’m entirely comfortable leaving the explanations regarding my work to the viewer. After I create a painting, the work is finalised. My influence ends there. The relationship between a painter and the viewer is always a Rorschach test. The relationship is a mirror itself, with the viewer perceiving the images as they are filtered through their own reality.

In the act of observing and evaluating art, people arrive at conclusions based upon their own awareness and varying life experiences. With this in mind, I think the viewer has a large participation in the experience of art; the artist creates the picture and the viewer creates the meaning.

Credits:

1. STEBUKLINGAS DRUGELIS. Painting by Hawk Alfredson.

2. Holographic Healer. Painting by Hawk Alfredson.

3. August in Wonderland. Painting by Hawk Alfredson.

4. The Dream Ambassadors. Painting by Hawk Alfredson.

5. Gypsum. Painting by Hawk Alfredson.