Data is Ryoji Ikeda’s (b. 1966) material of choice. The Japanese creative, born in Gifu and now living between Paris and Kyoto, is one of the world’s leading composers and media artists. He is best known for crafting immersive live performances and installations that lie at the intersection of sound, mathematics and visual art. Ikeda transforms data into electronic musical scores and bold light projections, creating high-intensity experiences that explore the unseen dimensions of our physical and digital spaces – from DNA sequences to binary code – whilst engaging with the rapid digitalisation that has transformed societies across the world.

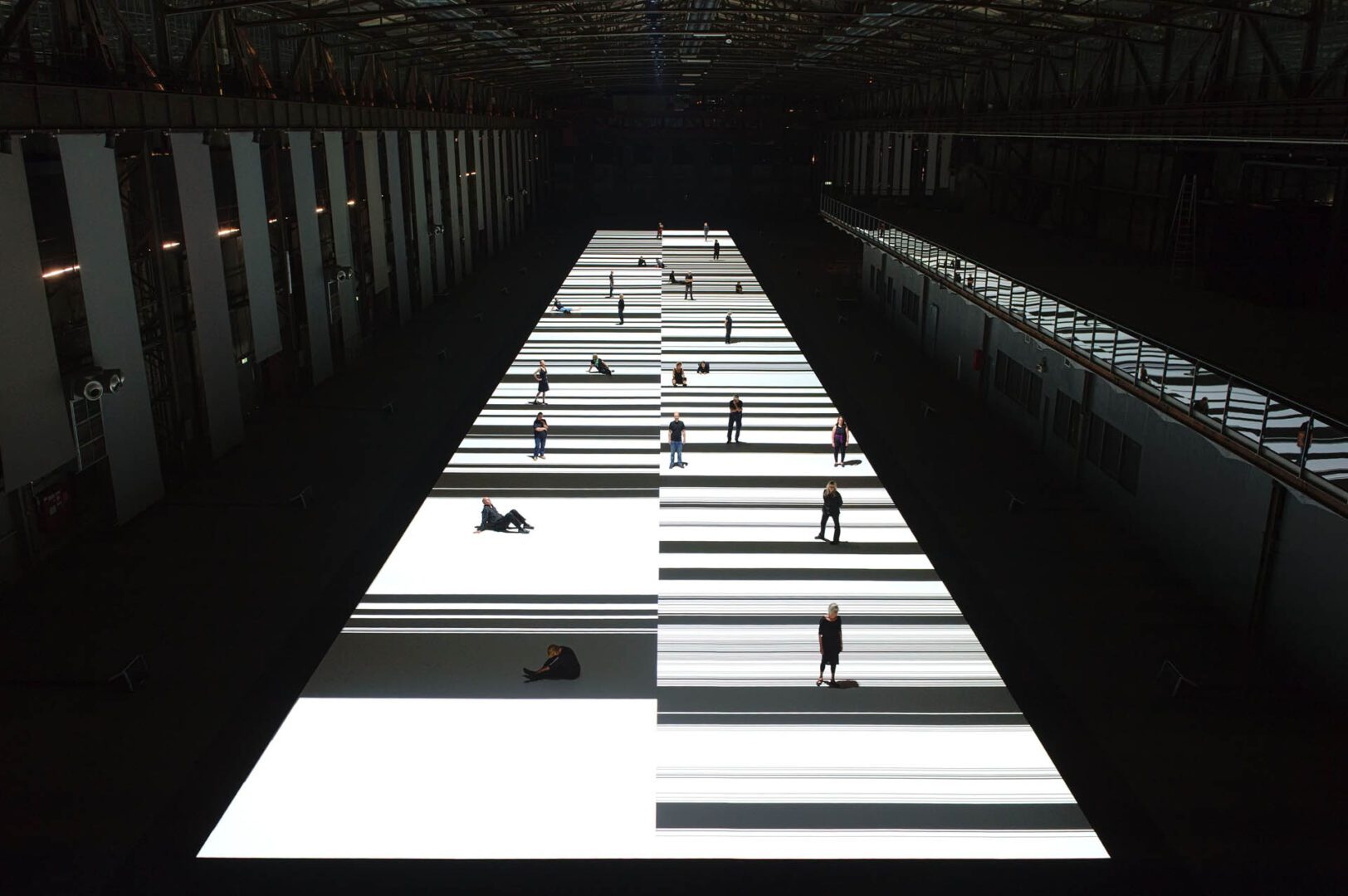

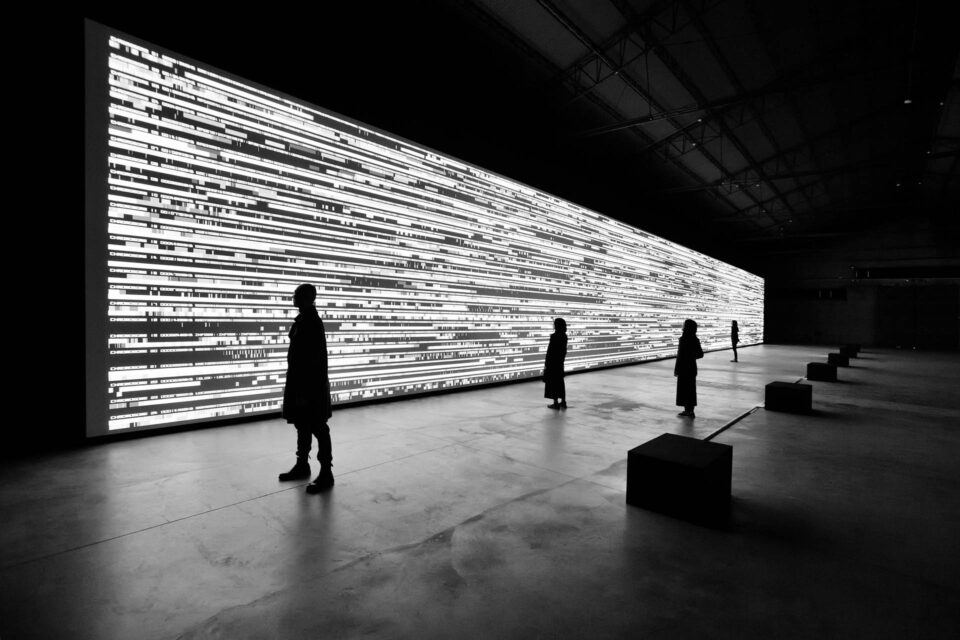

Ikeda’s practice is grounded in research, producing works like test pattern (2008-), which converts text, sounds, photos and files into barcode-like flashing walkways of 0s and 1s, and datamatics (2006-), a series of experiments spanning audiovisual concerts, installations, publications and CDs. His exhibits are spectacular, with light patterns strobing, flowing and scanning all around the audience. Ikeda has showcased work at major institutions worldwide, from the Barbican Centre and Somerset House in London, to the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo.

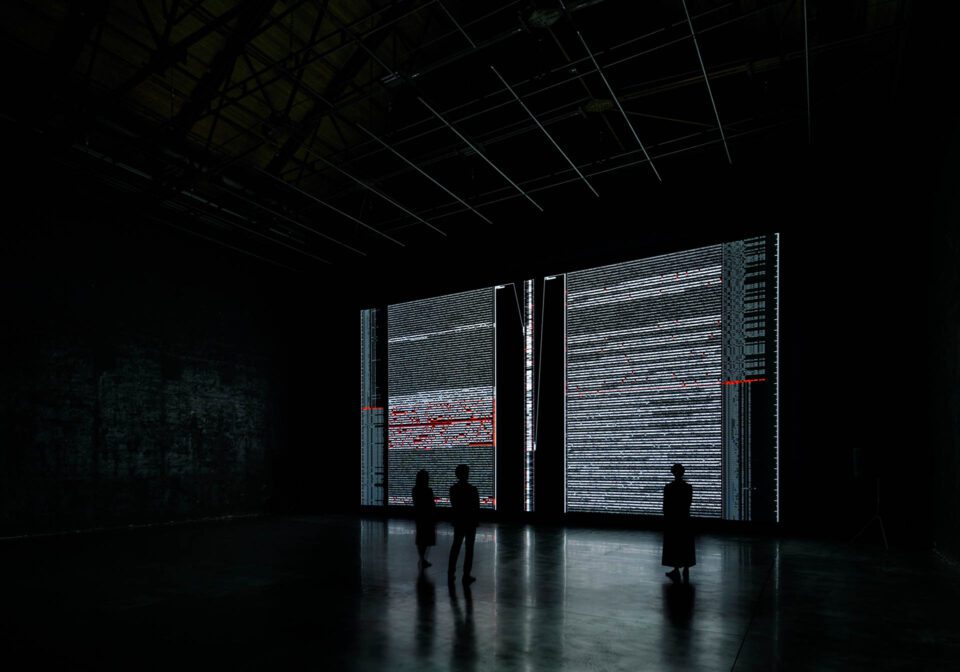

Now, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta presents the US debut of data-verse (2019–2020), a trilogy of immersive light and sound installations commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. This is the culmination of over two decades of research, featuring floor-to-ceiling video pro- jections that visualise data from mathematical theories and quantum physics. data-verse incorporates open-source im- agery from institutions such as NASA, CERN and the Human

Genome Project, and transforms huge data sets into visual outputs through self-written programs, arranged with an electronic musical score. The show also includes all-new site-specific works alongside existing pieces such as data.gram, an 18-monitor installation that deconstructs, analyses and recombines information from the trilogy. We sat down with Michael Rooks, the High’s Wieland Family Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, ahead of the show’s opening.

A: Where did the idea for this display come from? What drew High Museum to programme Ikeda for spring 2025?

MR: I travelled to Taiwan in October 2019 when Ikeda’s survey was on view at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum. I intended to spend a couple of hours there to see everything on view, but found myself in Ikeda’s exhibition the entire day – almost eight hours. Because Atlanta is a hub for commercial film, it seemed to me that Ikeda’s mind-bending compositions of light and sound would provide our audience with a completely different experience of time-based art. It generates meaning independent of linear narrative or verbal expression, but is still based on concrete language: data.

A: What are the key things we should know about Ikeda as a creative? How would you describe his practice?

MR: Ikeda was a member of the Japanese artist collective Dumb Type, a cross-disciplinary group of individuals who critically engaged with the evolving tech landscape of Japan through various art forms. He then established a solo career as a minimalist composer. The most audacious musical composition to date is A [for 100 cars] (2017), which was inspired by György Ligeti’s Poème Symphonique For 100 Metro- nomes (1962), only Ikeda’s piece is performed on the sound systems of 100 automobiles. Concurrently, he developed a body of large-format light and sound installations taking the form of spatial visualisations of data, mathematical theories, quantum physics and other branches of knowledge.

A: Let’s talk about data-verse (2019-2020), which is at the heart of this show. In a nutshell, can you explain what it is, how it is going to look, and the way it works?

MR: Like his music, Ikeda’s visual compositions are iterative. Consequently, data-verse is the culmination of more than two decades’ research-based work. It takes the form of a triptych, presented together, side-by-side. This is important, because each chapter’s sound and image synchronises with the others. The seemingly endless flow of graphics and information fluctuates between the microscopic and macroscopic, exploring human biology as well as the unimaginable depths of the universe. Unlike his earlier installation work, data-verse incorporates colour and visuals through open-source data obtained from NASA, CERN and the Human Genome Project.

A: Ikeda’s work is multi-sensory and, as such, has been described as “overwhelming.” What can attendees expect from the experience of stepping inside this exhibition? Is there anything people will find surprising?

MR: There’s nothing that the audience can expect to find before entering the exhibition, because Ikeda is little known in the USA and his work is unlike anything they will have ever experienced before. When you encounter Ikeda’s installations, it feels as though you’ve been swept up by the powerful undercurrents of a river – in this case, a digital one. The combination of data flow and sound is spellbinding. Perhaps one surprising thing will be how Ikeda’s work subverts assumptions that media-based art is largely sequential – time-based – rather than something based on patterns that describe or re-present time itself.

A: Ikeda is producing fresh, previously unseen works for this display. What can you tell us about those?

MR: The new work Ikeda is creating for the exhibition is somewhat like the musical structure of theme and variations, based on ideas generated by his decades of research and presented in a variety of new ways. In this case, incorporating the architecture of the museum to create a dynamic whole in which the viewer must negotiate, and then renegotiate, their own bodily relationship to the physical space ac- cording to Ikeda’s various modes of presentation – whether on the ground, overhead, or in an immersive environment.

A: Does this show differ from other presentations High Museum of Art has hosted in recent years? How do you think – or hope – audiences will respond?

MR: In the past, the High has shown primarily single and multi-channel video. This is the first large-scale, media- based exhibition that the High has ever presented. It will grab the attention of a generation for whom technology is second nature. We hope people will come curious and leave even more interested in the visible environment around them, as well as the invisible world we all carry around every day in the form of a smartphone. If people respond to Ikeda as I did in Taipei, they’ll want to come back to see the show again – it’s an expansive and mind-altering experience.

A: Why is Ikeda’s decades-long exploration of infor- mation technology so prescient today? What can his practice teach us about the world in which we live? MR: Ikeda’s work is quite relevant now because of the collapsing of time and space in real life. Borders are porous or non-existent, except for political ones, and the proximity between the micro- and macro-verses we live in simultaneously has made them almost indistinct – in other words, data streams and live feeds are just as “real” to most people as the ground beneath their feet and the sky overhead. I would argue that Ikeda’s work is funda- mentally philosophical – it’s about the meeting of horizons of knowledge, and so it is, in that sense, timeless. Data-driven decisions are precipitously changing the way people relate to the world around them. His work invites audiences to rethink conventional relationships between sound and image in our tech-saturated lives.

A: Ikeda works with data from renowned scientific institutions, and is one of many contemporary artists breaking down the traditional boundaries between art and science. What are your observations on how interdisciplinary programming has developed in recent years?

MR: The best is being done by academic centres, such as Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, which unites artists with scholars from other specialised fields and areas of knowledge to collaborate on projects. There are also ground-breaking tech-centred programmes such as artist residencies like NASA’s GEODES program and Eyebeam. Most general museums will always be play- ing catch-up when it comes to presenting technically complex works, like that of Ikeda, Zach Blas, Hito Steyerl, or Pierre Huyghe and others, since the practical needs of presentation – hardware, for example – are always changing, unlike those of more conventional art forms.

A: Looking towards the future, what is next for Ikeda?

MR: Given Ikeda’s wide-ranging interests and his insistence that the architectural envelope for the presentation of his audio-visual work is fundamental to it, comprising a unified whole, I would speculate that architecture might represent a future stage in his career. The designing of an architecture – a smart architecture – to not only house but also to, somehow, give form to sound and image would contribute to Ikeda’s ambitious vision of a total artwork in which various forms and concepts are integrated.

A: What can we expect from the High throughout 2025?

MR: data-verse is one of several diverse exhibitions the museum is offering in 2025 – beginning with an exhibition of drawings collected by a local art teacher that explores modes of abstraction in New York and Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, to the career of Kim Chong Hak who rejected abstraction for realism in the late 1970s and who sought to reclaim a unified Korean identity by channelling 1,000 years of Korean landscape painting. These are all firsts which represent the wide- ranging interests and priorities of our audience in Atlanta.

Ryoji Ikeda: data-verse | High Museum of Art, Atlanta 7 March – 10 August

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image credits:

1. test pattern [100m version], audiovisual installation, (2013) © Ryoji Ikeda. Photo by Wonge Bergmann. Courtesy of Ruhrtriennale 2013.

2. data.flux [12 XGA version ], audiovisual installation, (2017). © Ryoji Ikeda. Courtesy of Parallax 2017.

3. data-verse 3, audiovisual installation, (2020). © Ryoji Ikeda. Commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary. Photo by Takeshi Asano

4. test pattern [100m version], audiovisual installation, (2013) © Ryoji Ikeda. Photo by Wonge Bergmann. Courtesy of Ruhrtriennale 2013.

5. test pattern [no12] (extended version), audiovisual installation, (2017/2020) © Ryoji Ikeda. Photo by Jack Hems. Courtesy of 180 The Strand.