In 1979, Richard Avedon was best-known in the world of fashion and celebrity portraiture, having worked for Harper’s Bazaar, The New Yorker and Vogue. He’d photographed Andy Warhol, The Beatles, the Chicago Seven, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ezra Pound and Marilyn Monroe. This was a veteran of camerawork. So when Mitchell A. Wilder, director of the Amon Carter Museum, Texas, approached Avedon about a new project, it was a turning point in his career. For five years, he travelled across the American West to document its inhabitants, including miners, herdsmen, salesmen and transient people. The result was In the American West, a book that marked a pivotal moment for both the artist and contemporary portraiture.

This spring, Gagosian London presents Richard Avedon: Facing West, an exhibition of rare prints, forty years on from their creation. It features 21 images, some of which have not been displayed since their debut in 1985. The show is particularly special as it is curated by the photographer’s granddaughter, Caroline Avedon. In an interview with AnOther Magazine, she said: “The sheer volume of people, all so unique and beautiful in their own ways, sparked a very intense admiration for the project.” In returning to the series four decades after its unveiling, Facing West prompts reflections on its status as its maker’s magnum opus.

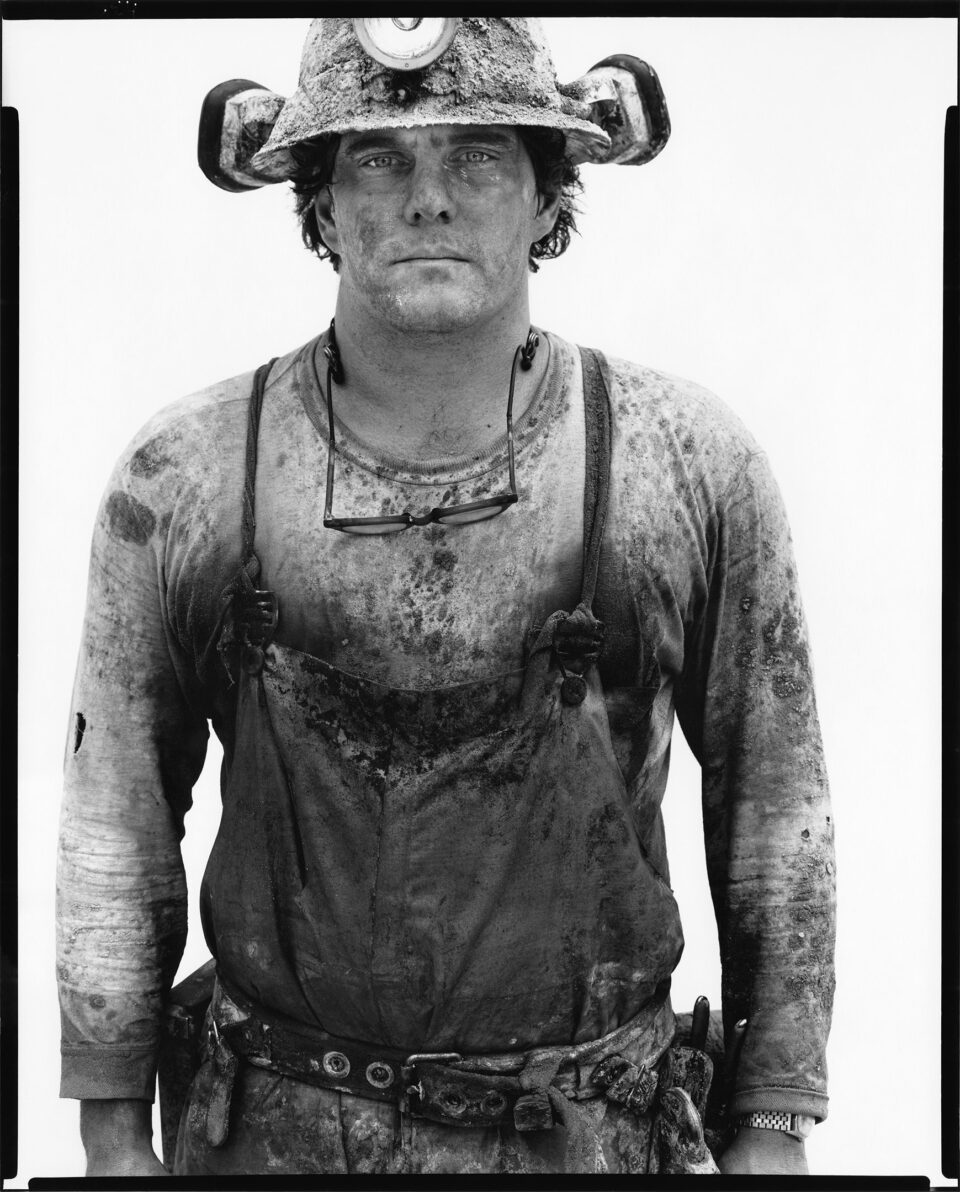

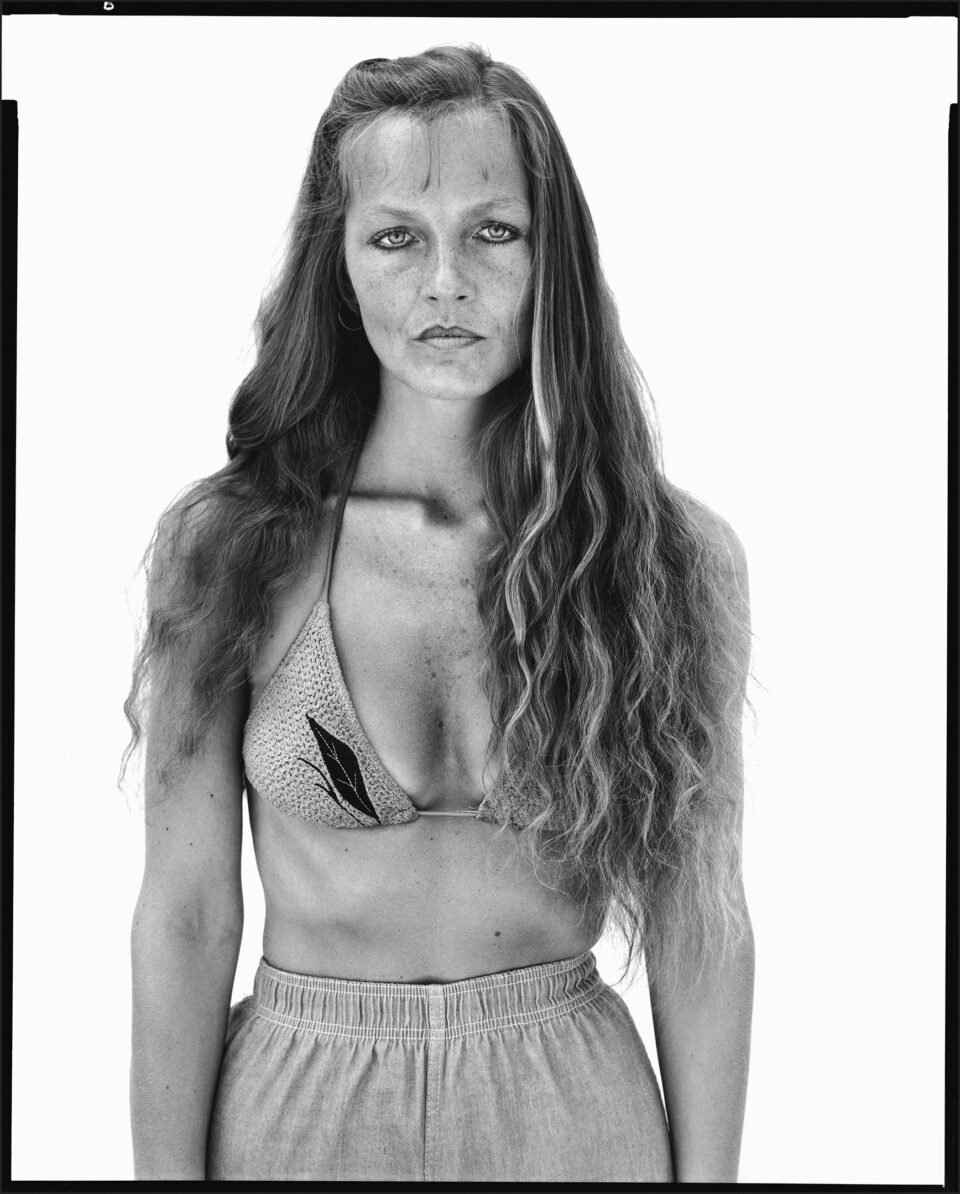

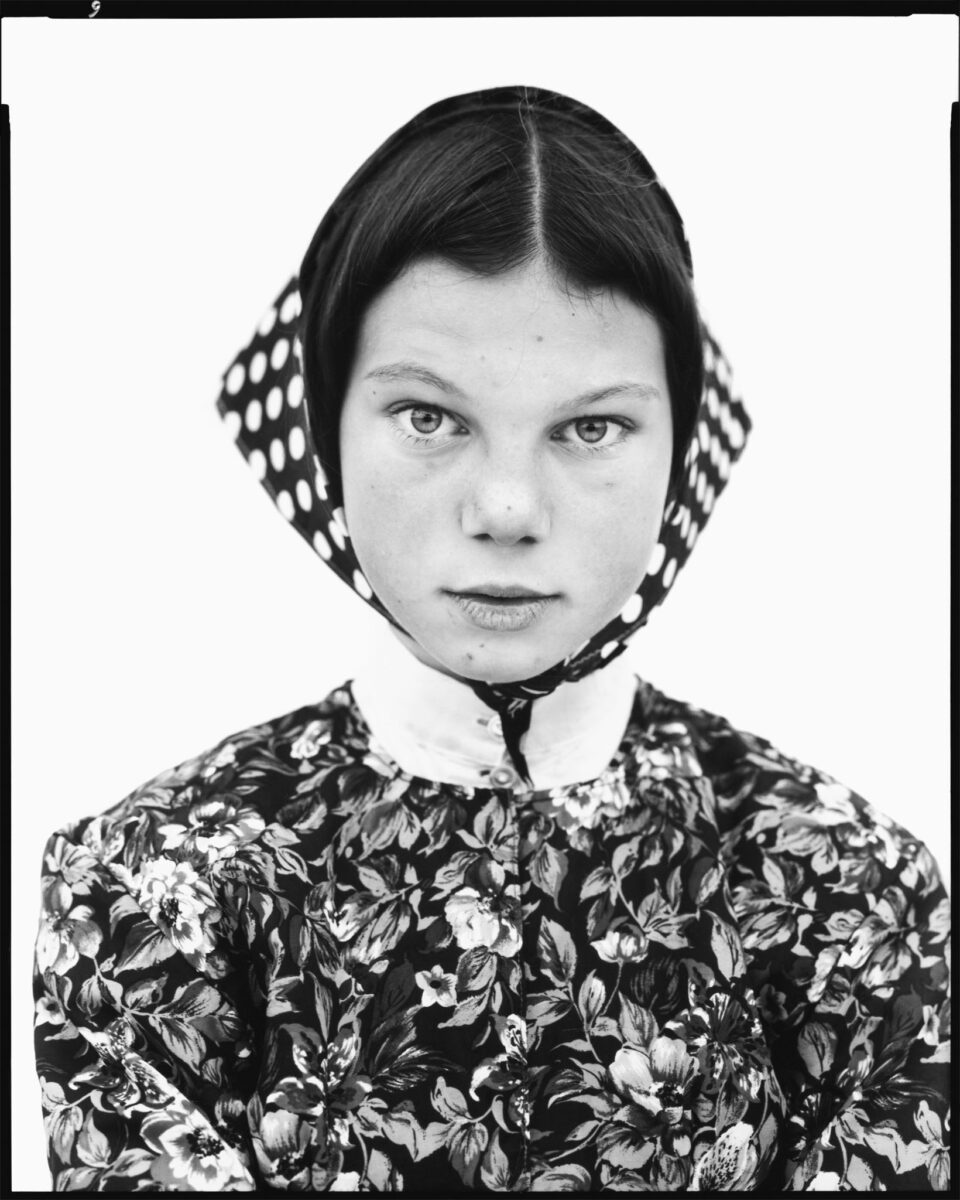

Avedon spent five years, from 1979 to 1984, travelling to 21 US states. He conducted more than a thousand sittings, finally producing 126 images that made up In the American West. Assistant Laura Wilson made countless introductions with local people, who represented a range of professions and rural pastimes, as well as often overlooked areas of society, such as drifters and coal miners. In this, the artist was a forerunner of 20th century photographers who turned the lens upon those marginalised or forgotten by society. Think Nan Goldin’s tender and unflinching snapshots of LGBTQIA+ subcultural communities, particularly those dealing with the devastating consequences of the AIDS crisis, or Mary Ellen Mark’s focus on those who lived “away from mainstream society and towards its more interesting, often troubled fringes.” Avedon sought human connection, often confronting the realities of suffering whilst conveying the hidden strength of his subjects, instilling the project with a sense of hope.

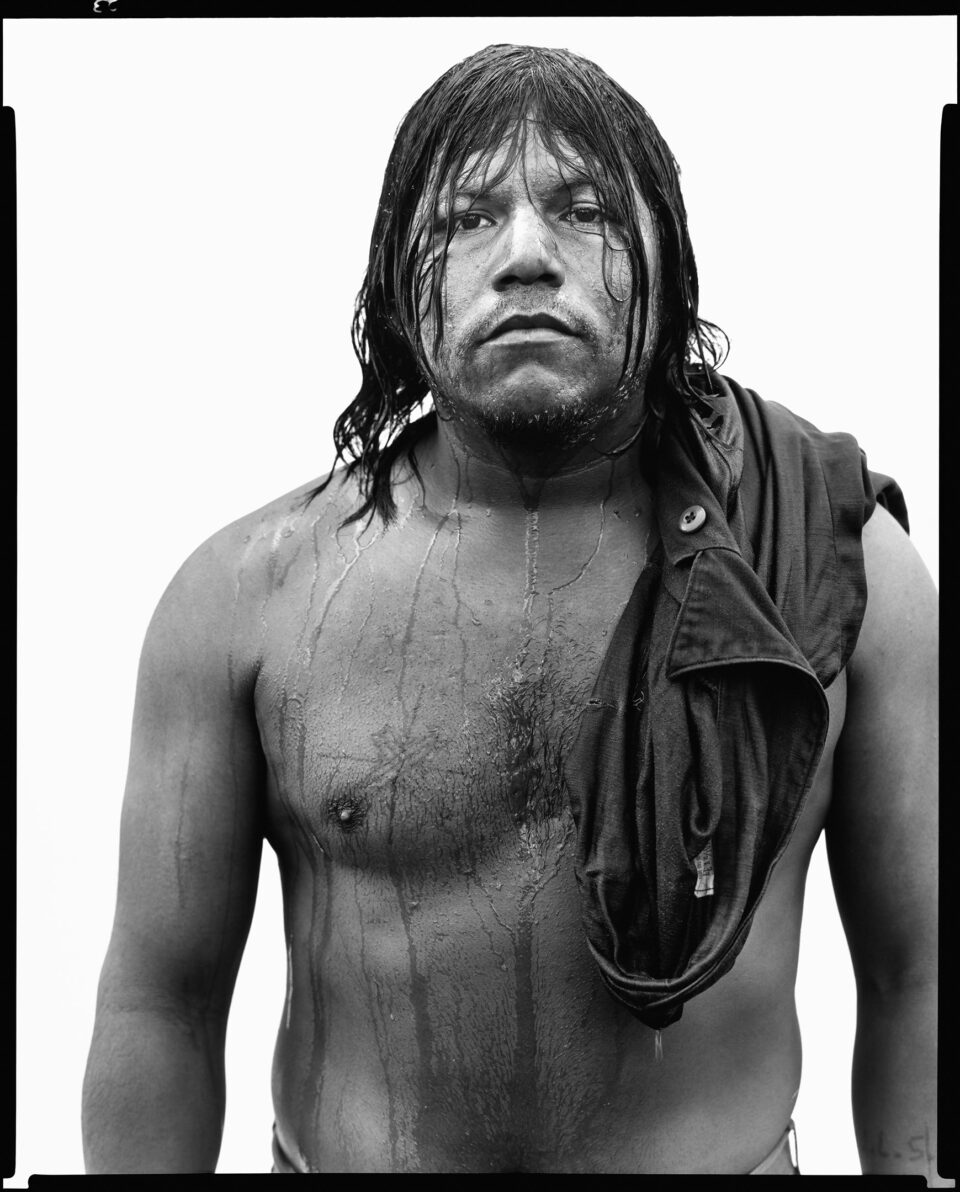

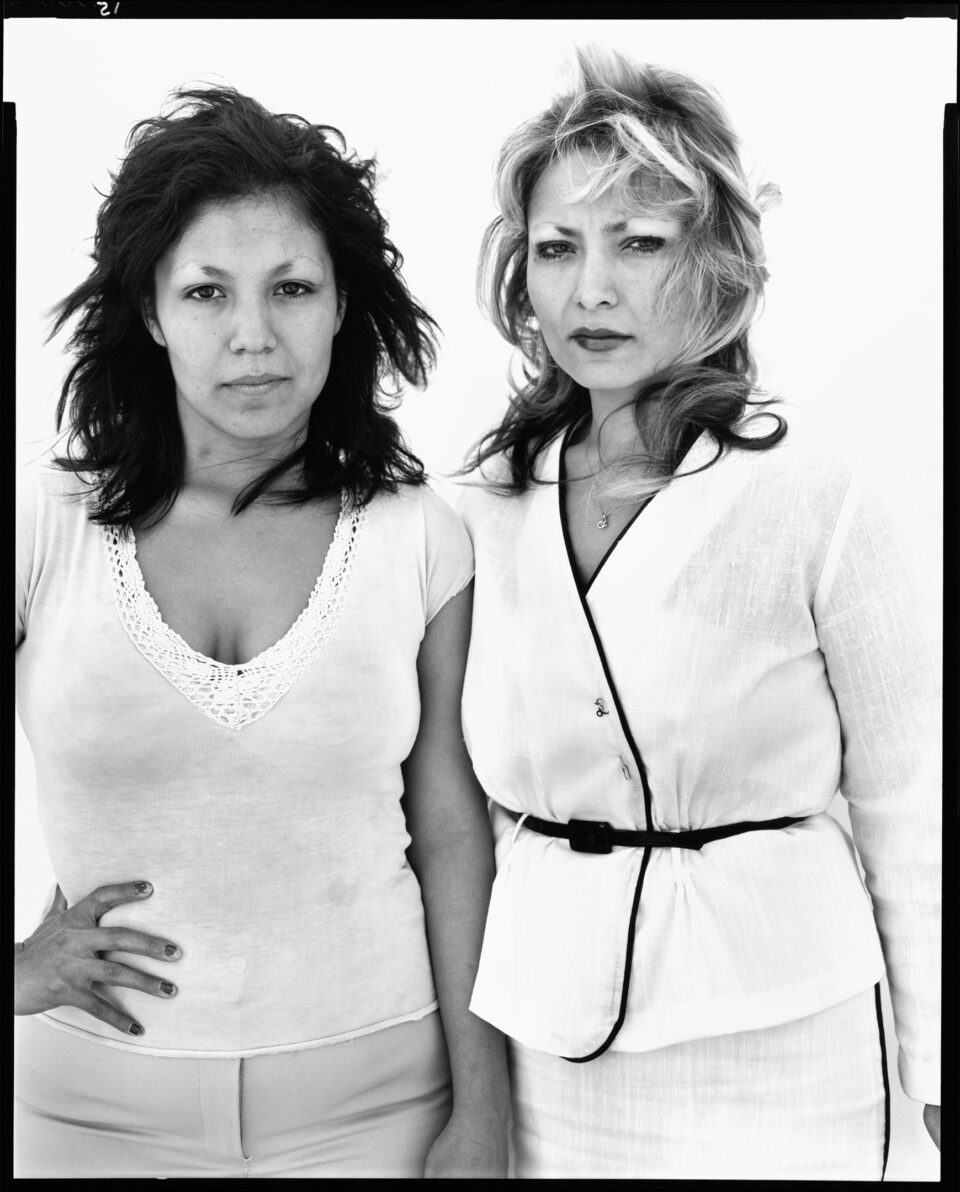

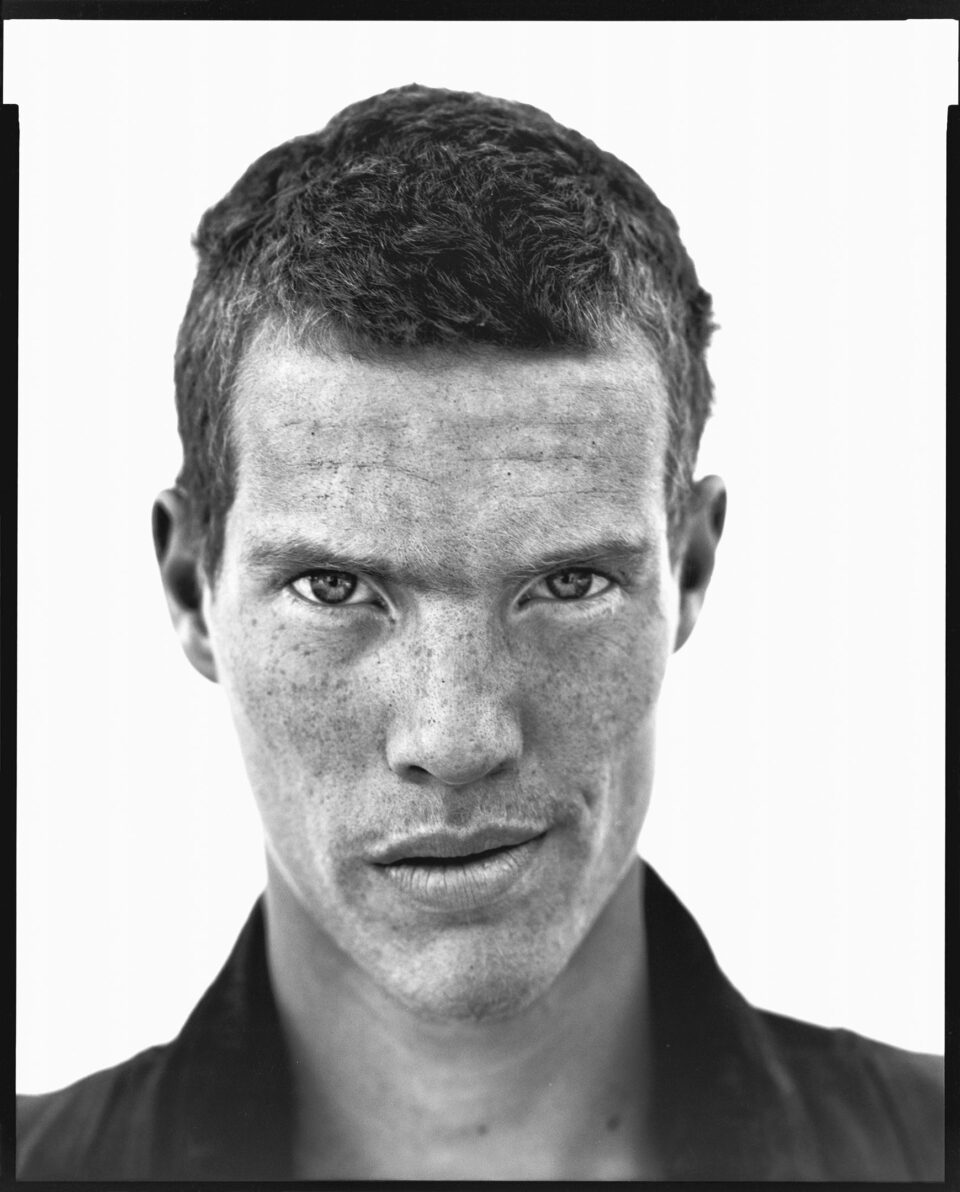

Each sitter is named and defined, an approach that resisted the anonymity typical of large-scale documentary portraiture. The choice to offer a detailed backstory means now, forty years on, the images continues to have a rich and tangible history that other works often lack. We are able, as 21st century audiences, to reach back and understand the life of the people looking out at us from the image. One such person is coal miner James Story, whom Avedon compared to Saint Sebastian for his embodiment of both strength and innocence. Also displayed in Richard Wheatcroft, a rancher from Jordan, Montana, who was photographed twice, once in 1981 and again in 1983. In a diptych of Wheatcroft, at first glance he appears to have barely changed in the years between shoots, but closer inspection reveals the subtle wear of life.

What’s clear is that Avedon strove to maintain the individuality and humanity of his subjects, often striking up friendships and returning to them time and time again. However, this attempt was not enough to satiate critics, who questioned how a photographer from the East Coast, who typically focused on fashion and celebrity, would go West to record hardship and suffering. In one particularly acerbic review in The Washington Post in December 1985, Paul Richard wrote: “These pictures are illusions. They tell us more about Manhattan’s manipulative theatrics than they do about Montana, and more about the artist than they do about the West.” It’s a discussion that rumbles on into today’s contemporary art scene, with questions of agency, representation and objectification defining discussions around photography. One 2025 headline from The Telegraph read “the ‘objectification’ of working-class life by outsiders has led to a century of ‘misrepresentation.’ It’s time for radical reframing.” Avedon himself does not clear himself of these questions, describing the series as capturing “a fictional west…I don’t think the west of these portraits is any more conclusive than the west of John Wayne.”

In The American West was groundbreaking because it complicated the picture. It did not seek to answer every question, reflect every nuance, instead it asked new ones. Each image represented a radical departure from the traditional depictions and glorifications of the legend of the West, captured by earlier figures like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. It forced viewers to consider the lives of those acting out their everyday routines in a land that often failed to live up to the American Dream. Here, the dialogue around identity, class and the complexities of human experience are played out. Forty years on, the work endures not because it resolves these tensions, but because it makes them impossible to ignore.

Richard Avedon: Facing West is at Gagosian, London 15 January – 14 March: gagosian.com

Words: Emma Jacob

Image Credits:

1&7. Robert Dixon, meat packer, Aurora. © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

2. Joe Dobosz, uranium miner, Church Rock, New Mexico, June 13, 1979. © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

3. Charlene Van Tighem, physical therapist, Augusta, Montana. © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

4. Freida Kleinsasser, Hutterite Colony, Harlowton, Montana, June 23, 1983. © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

5. Unidentified, migrant worker, Eagle Pass. © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

6. Annette Gonzales, housewife. © The Richard Avedon Foundation.