Review by Colin Herd

Timed to coincide with Richard Demarco’s 80th birthday, the current show in the impressive and expansive galleries of the Royal Scottish Academy celebrates his unique contribution to the visual arts in Scotland. Demarco was one of the co-founders of Edinburgh’s legendary Traverse Theatre in 1963, and went on to establish The Richard Demarco Gallery in 1966. The Demarco Gallery inaugurated close ties with international avant garde artists, especially those in Eastern Europe. In groundbreaking shows such as 16 Polish Painters in 1967 and 4 Romanian Artists in 1969, Demarco introduced Scottish audiences to new tendencies in European art. The exchange worked both ways, and Demarco regularly secured corresponding exhibitions and opportunities for Scottish artists on the continent.

The result was a sustained period of mutually fruitful dialogue, engagement and collaboration. The spirit of these endeavours is perhaps best encapsulated in the Strategy: Get Arts exhibition, which Demarco held during the 1970 Edinburgh Festival at the College of Art. Strategy: Get Arts shocked and excited Scottish art circles with the sheer scale of its invention and vision. Works included a jet of water installed by Klaus Rinke to be negotiated like an obstacle by visitors, and an interactive ‘feast’ staged by Daniel Spoerri. Joseph Beuys performed Celtic Kinloch Rannoch: A Scottish Symphony, incorporating film by Mark Littlewood and Rory McEwen and a soundscape by Henning Christiansen. To a projected film of someone filming the mist on the moor, Beuys pasted gelatin to the walls, removed them to a tray and quickly tipped the contents over his head. Documentation including photographs and a striking A3 exhibition-publication from this piece forms the core of Beuys’ representation in the current show. Other exhibiting artists at Strategy: Get Arts included Dieter Rot, Blinky Palermo, and Gerhard Richter. Andre Thomkins participated in the show, but perhaps his greatest contribution was the palindrome that served as the title and that seems to sum up the exchange backwards and forwards that characterizes Demarco’s curatorial approach.

Inevitably, the question-mark over the current exhibition is whether it can recapture some of the thrill and excitement of the shows it commemorates. The curators have structured it around the work of ten artists with whom Demarco has had sustained engagement. Six of the artists represented are from continental Europe: Joseph Beuys, Marina Abramovic, Tadeusz Kantor, Paul Neagu, Magdalena Abakanowicz and Gunther Uecker. The remaining four are Scottish: Rory McEwen, Ainslie Yule, Alistair MacLennan and David Mach. The large, airy space of the central main-gallery is taken up with a new installation by Magdalena Abakanowicz of ten huge welded steel sculptures depicting figures from the legend of the Court of King Arthur. Somehow managing to look like animals, humans, and machines all at once, the sculptures emphasize dialogue and connections through the rhythmic way their shapes interact and the scar-like marks where they’ve been welded. It’s a striking focal point for the exhibition, from which the other rooms lead off, and Abakanowicz’s unmistakeably contemporary treatment of myth and legend has the advantage of helping to point the viewer towards a productive engagement with some of the historical aspects of the show, to move beyond its commemorative aspect.

In two new portraits for 10 Dialogues, David Mach renders Demarco’s head in collages made from what must be thousands of postcards. By doing so, he literally makes communication, correspondence and dialogue the very fabric of Demarco as local cultural icon. This recent work sits in interesting counterpoint to the documentation of an earlier piece, Local Hero from 1992, in which Mach made a life-sized sculpture of Demarco’s head out of coloured match-sticks in a tartan-style pattern, and then set it on fire in front of an audience, outside the Demarco Gallery. Mach’s piece is an astute comment on the cult of personality and on art-world myth-making, especially in light of the controversy surrounding the Arts Council withdrawal of funding from Demarco after his support of the imprisoned gangster-turned-artist Jimmy Boyle. The burnt-out relic-like head is presented here alongside a film of the ‘performance’, much of which is taken up by people un-dramatically standing around talking, taking pictures, and milling around. At one point, in fact in some ways the climax of the film, Demarco makes disparaging remarks about the concurrent show at the RSA.

There’s something distinctly dark and unsettling about David Mach’s burnt-out match-head. Similarly, the work of Gunther Uecker is uncompromising and challenging. His wall-mounted wooden sculptures made from spiky shards of stone, wood and white paint suggest trashed canvases and boards. The fearless blend of natural materials in self-consciously painterly sculptures suggests an uneasy frictional dialogue between the two elements. A similar tension exists in the work of Paul Neago whose brushed and worn steel sculptural ‘hyphens’ look like they might have been up from a beach as driftwood. They seem to hint at a conversation of symbols we can’t understand. Another highlight of the show is an installation by Alastair MacLennan, a room filled with uniform rows of steel bowls that act as mirrors, reflecting the light almost like a kaleidoscope. Even the smallest sounds, too, seem to rattle around the pristine curves and hollows. A deceptively simple work, it provokes a surprisingly expansive emotional effect.

My only criticism of 10 Dialogues concerns the title. Given the witty and playful name of the landmark Strategy: Get Arts, it really stands out that the curators have gone for what feels like a howling misnomer. From a photograph of Beuys with Lady Roseberry and Buckminster Fuller, to the films of Demarco in lively conversation, the postcards in Mach’s portraits, gallery-visitors whispering and the echoing voices in MacLennan’s sculpture, this show represents hundreds of dialogues and thousands of potential dialogues, not merely ten.

10 Dialogues continues at the Royal Scottish Academy until 9th January. www.royalscottishacademy.org

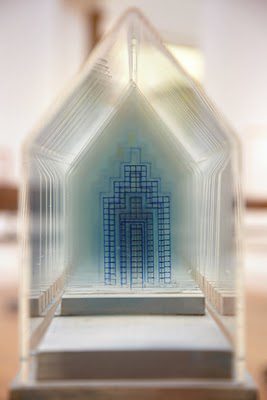

Image © Ainslie Yule 04 – Wave & Ziggurat (detail), 2009 – 2010