There are few locations that occupy a larger space in popular imagination than the American West. The region, according to most definitions, covers the entire USA beyond the Great Plains and includes 13 States. Settler colonies expanded into the area during the 19th century, pushing the frontier in pursuit of “Manifest Destiny,” displacing and harming Indigenous communities as a result. Here, the mythology of cowboys and their horses, shootouts and saloons with swinging doors, was born. Fast forward to the mid-20th century and Spaghetti Westerns like The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, and leading men like John Wayne and Clint Eastwood, cemented these stereotypes as a part of pop culture. Daniel Mirer first began photographing the area 30 years ago. He, like millions of others, was drawn in by its vast horizons and sweeping vistas. Yet, as the artist looked more closely, he began to see the traces left behind by humanity, like tattered tourist sites, rusting billboards, flooding parking lots and abandoned swimming pools. His images capture this juxtaposition, subtly deconstructing the legend of the American West. He joins a movement of artists who are bringing conversations about the climate crisis, colonisation and environmental degradation into the picture. David Benjamin Sherry reinvigorates the landscape tradition with an emphasis on queer identity, colour and magic, whilst Wendy Red Star draws on on pop culture, conceptual art strategies, and the Crow traditions within which she was raised. We caught up with Mirer to discuss Indifferent West, a new show that spotlights the reality behind the myth of the American West.

A: Take us back to the beginning. How did these images first come about?

DM: I grew up in New York City, where the landscape is vertical – towers, density, movement upward. Encountering the American West was like stepping into its opposite: a horizontal vastness that dwarfs the ego and makes you feel insignificant. That smallness is humbling, but also freeing – the horizon stretches endlessly and the land feels everlasting. Compared to the green, crowded, tree-filled East, the West’s openness struck me with its stark simplicity. Like many, I had internalised the mythical West through Hollywood films. I loved those Westerns, their imagery was seductive, even if they were a form of soft propaganda. In graduate school at California Institute of the Arts, I had the chance to “Go West” myself, as the old saying goes. Photography became my way of reconciling the myth with my lived reality. What began as a curiosity during road trips – seeking out the contradictions between beauty and destruction, dream and exploitation – grew into a sustained practice of looking critically at how the West is consumed.

A: The American West has long been mythologised. How do you disrupt these entrenched narratives?

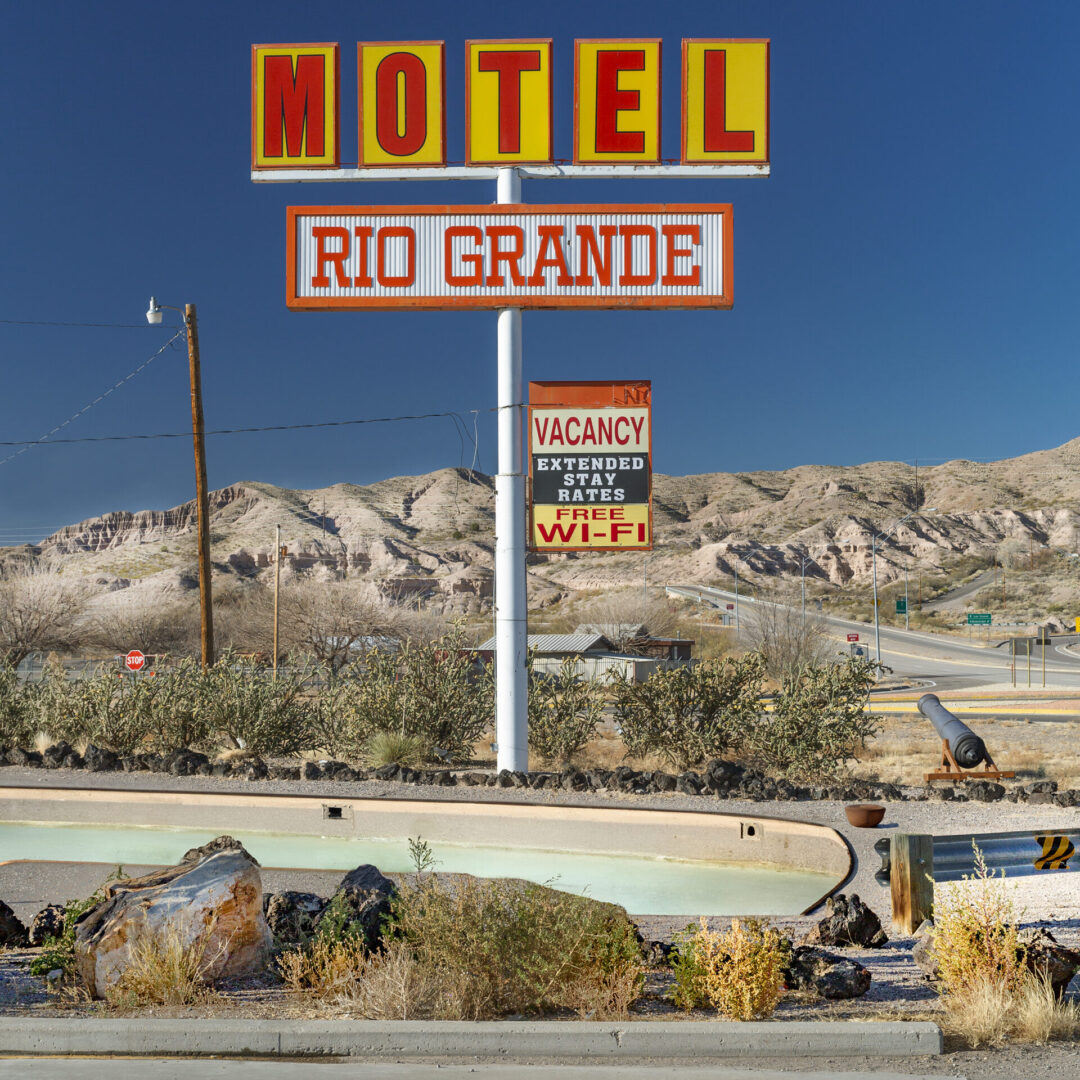

DM: I approach the West not as a frontier of promise, but as a stage where competing histories and politics collide. Rather than the heroic cowboy or the untouched wilderness, my lens focuses on the overlooked – roadside attractions, parking lots, abandoned infrastructure and sites of extraction. By focusing on these quieter, ordinary spaces, I aim to unravel Americana Hollywood and reveal the layered realities beneath it. The Western landscape is also inseparable from the Anthropocene. It embodies the complexities of this proposed new age: vanishing ice, rising waters, intensified resource extraction and the enduring legacies of colonialism. It is a place where forced climate migration and socio-environmental trauma intersect, making it not only a myth but also a mirror of our planetary crisis.

A: Talk us through your creative process. How do you get the right shot?

DM: I work slowly, often returning to the same place over years. I walk, I wander and I wait – letting the location reveal itself. Sometimes the photograph arrives by chance: a fleeting moment out of a car window that screams at me with kitsch, irony or a grand gesture of light falling across asphalt, or a mirage-like shimmer of heat on the horizon. Other times it’s about recognising patterns – how tourism reshapes the desert, how industry scars the land. My process is as much about patience and observation as it is about pressing the shutter. My images also aim to expose visual hypocrisies, which I find amusing and simultaneously unnerving. We are generations removed from the era of westward expansion, yet the myths have been naturalised. Hollywood rarely shows the forced removal of Native people – instead, it casts them as either content in co-existence or relegated to an afterthought. That’s where the indifference lies: the landscape itself becomes a backdrop, employed to cover over the histories we choose not to face.

A: Why do you shoot in square format, rejecting traditional landscape conventions?

DM: The square format resists the panoramic sweep we expect of the American West. It pulls the observer in, rather than stretching the view outward. By compressing the frame, the square forces attention to the constructed and fragmented nature of the scene. It’s less about grandeur and more about intimacy. The audience’s engagement is important, as it insists that every piece of the West contains meaning.

A: The exhibition accompanying book are titled Indifferent West – what does this name mean to you?

DM: The title reflects a paradox I’ve come to recognise in the West. On one hand, it has been endlessly romanticised, as seen in the glorification of cowboy culture, the idealisation of the Gold Rush, and the myth of the rugged individualist. On the other hand, the land itself is indifferent to human ambition. We narratives onto it, yet the desert doesn’t bend to those stories. At the same time, Indifferent West points to a cultural apathy toward the actuality of history and this place that is part of the country’s iconography. The collective image of the American West rarely grapples with what truly happened in this space, ignoring historical facts of continental colonisation. Instead, it has been built around nostalgia: the illusion of freedom, the promise of expansion and prosperity.

A: Indifferent West features 108 photographs, spanning 30 years. How has your perception of the Western landscape – and what it represents – evolved over time?

DM: When I first began, I saw the West through the lens of cultural spectacle – theme parks, neon signs, brash tourism. Since then, my focus has expanded to the deeper environmental and political stakes. Record-breaking temperatures, flooded basins, drought, extraction – all of these crises became impossible to ignore. The West today feels like a mirror of our larger Anthropocene moment: a place where climate change, consumption and mythology converge.

A: Your photographs often depict kitsch tourism and environmental degradation side-by-side. What does this juxtaposition reveal about American identity and consumption?

DM: It exposes the deep contradictions at the heart of American culture: the simultaneous desire to preserve and to exploit, to celebrate the West as untamed wilderness, whilst building strip malls on its edges. We want the postcard image, but we also want convenience, profit and expansion, often at the expense of the very lands we revere. I grew up surrounded by theatre and television, and those early influences taught me the power of subtext. In sitcoms, the real weight of the dialogue often came through double entendres or coded meanings – a kind of wordplay that added layers of irony and poignancy beneath the laugh track. That sensibility has carried into my work. Rather than slapstick humour, I use satire as a way to expose uncomfortable truths. A neon cowboy sign next to a drought-scorched landscape, or a fiberglass monument fading in the shadow of industrial machinery, these juxtapositions underscores the absurdity of our cultural imagination. Spectacle often masks crisis, and the irony is that our consumption of the West carries costs we collectively choose not to acknowledge.

A: In this era of climate crisis and cultural reckoning, what role should art play in shaping discourse?

DM: Art’s function is not to provide solutions – those belong to policy, science and collective action. Instead, art is an essential and powerful tool that asks important questions, critiques the status quo and encourages us to slow down in order to conceptualise and think ahead. It prompts us to see things differently, to notice what is overlooked, and to bring to light the issues that society often rushes past. It creates a pause in the noise of daily life, allowing reflection and questioning. Additionally, art can help challenge societal indifference. It creates a language for grief, reckoning and resilience. It holds space for histories that have been suppressed – such as the removal of Native communities, the exploitation of labour and the ecological traumas we inherit. By making these realities visible, art confronts the apathy that often surrounds them. In this context, my photography serves as a crucial intervention. It reveals the cracks in the façade: the drought-stricken reservoirs, the abandoned attractions and the scars left by extraction industries. These images may not resolve the crisis, but they can certainly puncture the illusions that still governs our imagination of the American West. Ultimately, art can shape public discourse by cultivating awareness and empathy. It reminds us that we are not separate from the landscape but entwined with it. This recognition may be one of the most powerful contributions artists can make.

A: Do you have a personal favourite photograph you’ve taken?

DM: Two images come to mind. The first is of a flooded desert basin where the horizon dissolves into a mirrored sky. This scene captures both beauty and unease, a world transformed by forces beyond human control. For me, it encapsulates the project’s balance between wonder and critique. The second image depicts two rusted, old cars stuck in the mud; this picture has become a metaphor for the current state of the political environment in the USA. Two old cars rusting under the desert sun, part of a long-gone industrial era of strength and prosperity, slowly being overwhelmed by the environmental effects that the cars themselves have created, only to be revealed decades later through water evaporation and drought. The cars themselves are not only a nostalgic reminder of what was, but are a warning about our current moment. The country, government and policies are stuck in the mud, they can’t move forward and can’t move back. Forever sinking under its own weight, rusting away.

A: What’s next? Anything we can look forward to?

DM: The Elliott Gallery exhibition and accompanying book represent the culmination of three decades of my work, but I view them as a beginning rather than an end. I am actively exploring the intersections of landscape, politics and climate in the Western USA, expanding into new regions and incorporating video with photography. The story of the West is still unfolding, and my work is dedicated to documenting it.

Indifferent West is at Elliot Gallery, Amsterdam until 11 January: elliott.gallery

Words: Emma Jacob & Daniel Mirer

Image Credits:

1. Motel Rio Grande, New Mexico 2022.

2. Alabama Hills, Lone Pine, California 2023.

3. Sexee Nude Ladies, Tucson, Arizona 1999 digitally scanned 2023

4. Mount Whitney, Lone Pine, California 2022.

5. Lanes Lounge, Colorado 2017.

6. Steak in Texas, 2016.