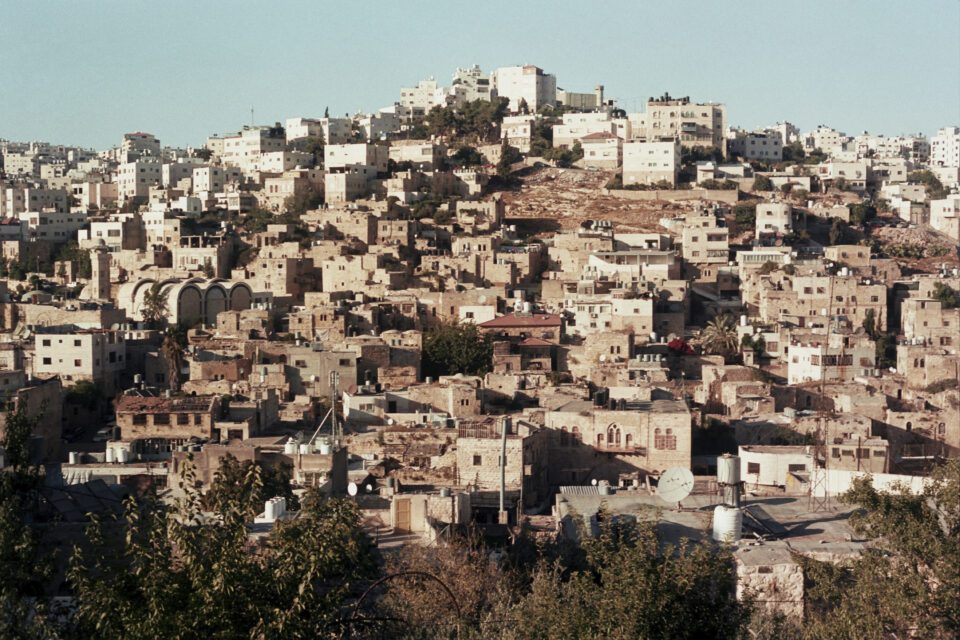

In September 2023, journalist and photographer Barbara Debeuckelaere travelled to Palestine. Her destination was Tel Rumeida in Hebron, the only city in the West Bank with an Israeli settlement at its centre. It was the latest in a series of visits to the region, where she had gotten to know local communities. This time, she had a bag of analogue cameras with her, which she gave to women and girls from eight families. Over the next month, they tenderly documented their lives – capturing domestic moments that are often absent from news stories. The collection of images – which totaled more than 1,000 in just four weeks – became part of ‘Om/Mother, a powerful book that shows the Palestinian women of Tel Rumeida documentation of their lives, homes and immediate surroundings. By showing the world their determination to continue their daily lives under occupation, these women are participating in the ultimate act of resistance. The photographs were taken weeks before the Hamas attack on 7 October 2023, and the Israeli bombardments on Gaza and the West Bank that followed. Two years on, an estimated 60,000 Palestinians have been killed, whilst countless others are displaced or starving. Leading experts, including Amnesty International and, in recent days, the UN, have declared the situation in Gaza a genocide. ‘Om/Mother is now on display at FOMU, Antwerp, where original images are presented alongside updated information and interviews, offering a deeper insight into the women behind the cameras. Debeuckelaere speaks to Aesthetica about the project, which she described as a “feminist work of love.”

A: Can you tell us about how this exhibition came about?

BD: Before it was an exhibition, ‘Om/Mother was a photographic project and a book that was published last year by The Eriskay Connection. We held a book launch at FOMU in 2024 and I had an interesting talk with Maartje Stubbe, the director of the gallery, to discuss further possibilities for the project. So I was not completely surprised when she called me in spring of 2025 to ask if I would be interested in curating an exhibition on ‘Om/Mother. This provides a great opportunity: for the Palestinian women with whom I am working, for our joint project and our book, and for having another reason to talk about Palestine. Luckily, I already had a trip to Hebron planned because we were showing the project in Wonder Cabinet, Bethlehem, so that the women could see their own work presented on the wall. On that trip, I also taped interviews with all eight participating families, we talked about the current situation in Gaza, the power of art and the impact of the project. These interviews, along with photographs of the region and the occupation, were edited into a video installation. This became an essential element of the FOMU exhibition. It was also very moving to hear the women talk so beautifully about what the project, the act of photographing and the book meant to them. Several of them talked about how they finally felt seen.

A: The show is made up of photos taken by 50 women from eight families. Why did you choose to focus on the female perspective, and in particular mothers?

BD: Tel Rumeida, Hebron, is a Muslim neighbourhood. It is also one of the most complex and violent places in the West Bank. Women of Indigenous populations are often targets of abuse and are largely oppressed – it’s unsafe for them in the streets. On social media and in press articles coming from this region, you mostly see men: the Israeli settlers and their children, the soldiers “protecting” these settlers from Indigenous communities and the Palestinians themselves – these are all men, hardly any women in sight. Of course, women go to work or bring their children to school but they do not pass a lot of social time on the streets, like talking to neighbours or watching their kids play, simply because it is very unsafe in public spaces. So as a woman I was curious about the female experience of this physical and verbal violence. Through Issa Amro, a human rights activist from Tel Rumeida, I met around ten families from the village in February 2023. I visited them and heard their many stories of the injustice, inequality, lack of services, pestering, name calling – I even experienced some of this myself. I quickly realised that women and mothers are the driving forces of family life here and that staying in this place of oppression is a huge daily effort. One third of the houses has been left abandoned, standing empty, so those who do stay – taking care of their kids, trying to build a life as normal as possible – are showing that nothing could force them to leave their land or house. Simply living here is the ultimate act of resistance.

A: Tel Rumeida is the only city in the West Bank with an Israeli settlement at its centre. You’ve described it as a “microcosm of settler violence.” Could you tell us about how this location influenced the series?

BD: As a journalist for public radio and television, I had been in the West Bank several times, and Palestine will stay with me forever. But I have to say that my visit to Tel Rumeida, especially my encounter with Issa Amro, was life changing. Amro believes in non-violent resistance, he is strong headed, eloquent, knows his rights, he is internationally popular and a real pain in the ass for the Israeli. I was with him when he was violently beaten by an Israeli soldier for no reason at all, while he was leading the New Yorker staff writer Lawrence Wright around town. My footage of the incident went viral worldwide. I knew there and then that I would not let go of this place, that my friendship with Issa, the activists and families will be for life. Every conversation you have there is intense. Every step you take in the West Bank is too. As a westerner, you choose where you walk: do you walk the easy road, where you and Israeli can walk and drive but where Palestinians cannot, or do you follow your Palestinian friends on a detour road, through the dirt alleys? That is all political. Also, the news we hear in the west comes very much alive when you are there. In H2, the part of Hebron that is under Israeli military control and where Tel Rumeida is also situated, there live some of the most radical settlers in the West Bank, who believe in a greater Israel, in annexing the land for only Jewish people and expelling the Palestinians. In this toxic male environment, and with so little agency for the Palestinians and women specifically, it seemed like a very good idea to give some control back to the women by handing them the camera. The lens is their only weapon to document violations of human rights and expose them to the outside world. It gave them the opportunity to photograph whatever they wanted, their children, their houses, cats, plants, the light on the tiles, they can show the world they are proud of their land. Their lives are beautiful and rich, despite the context of violence that surrounds them.

A: You had over 1,000 images to choose from. How did you approach the task of making the selection?

BD: The curation of the book was first done together with Carel Fransen of The Eriskay Connection, with whom I made a first broad selection. Then I asked each family individually if they could agree with the selection or if they had some pictures included, they did not want to be published after all. One picture I remember was deleted, but for the most part we agreed easily. The fact that the book is a collective effort, in joint authorship, and the individual photographs are not assigned to this family or that woman, also helped in overcoming a sense of reserve or timidity to show personal objects or scenes. Some women have contributed text to the book, on what a home and what Hebron means to them, which provided a layered and beautiful understanding of their love for Palestine. In general, up till now, for each new presentation, I make a proposal for the group, whether it was the book or for a new exhibition. And then the women of Tel Rumeida can respond to it and I take of course into account any remarks they might have. We talk regularly on new events happening for the project and every time I try to have the voices of one or two women heard. And coming up next is a new exhibition of ‘Om/Mother in Bologna in October.

A: The pictures were taken in September 2023. In the two years since, the genocide in Gaza has claimed more than 60,000 lives and in Tel Rumedia, a third of homes stand empty with many residents either killed or forced to flee. How do you contextualise images in a landscape that continues to worsen?

BD: Exactly in these dire times, when Israel is committing the worst war crimes imaginable towards the Gazan people, using starvation as a weapon, slaughtering journalists, health workers, maiming children, it is more important than ever to do everything in our power to stop them; push our politicians to cut ties with this genocidal regime; impose sanctions; try to break the Israeli blockade of aid; and help document and protect Palestinian life in the West Bank. But we also need to listen much more Palestinian voices and look at Palestinian art. Israel tries everything in its power to erase archives, heritage and cultural life, so this series is part of that resistance. It is more essential than ever to share these images. In the interviews I did in 2025, that are shown in FOMU, the women say exactly that.

A: Is there a particular photo from the collection that really resonates with you?

BD: I like so many images but if I must, I’d choose this pinkish image of the garden in Bethlehem University. This was on a particular roll of film that I apparently had used before, so many images on this role are double exposures and that proved to be interesting. You see some strange lines that most likely come from a portrait, but the garden is dominant. The pink and blue colouring was there in the first scanning and I left it like that. This picture is taken by Nidaa, a girl with a difficult home situation. Her mother is ill and her father, who she was very close to, had just died. Nidaa is incredibly strong and smart. She is studying to be a bioengineer at the Bethlehem University, as well as working in a store to pay for her studies and support her mother. She perseveres and always stays friendly and hopeful. When I look at this garden, I think of her.

A: Many of the scenes depict domestic moments like cooking, resting or playing. How do they challenge dominant visual narratives of Palestinian life under occupation?

BD: The images were taken by the women during the month of September 2023. They all used small analogue cameras and the photographs were often blurry, full of light leaks or crooked framing. This conveyed something of the meaning of what a home is, namely messy, ambiguous, colorful and diversified. This is very much in contrast with the political context of oppression. You could say that the digital camera, with its sharp and precise registrations of reality, is more the instrument of the press, of politics, maybe more masculine. The analogue gives another vibe – it’s beautiful, but also radical. These women are showing by cooking, playing, taking care of plants and trees, they are here to stay.

A: Two of the photographers, ‘Om Wisam and Nidaa, will attend the exhibition in person. What does their presence mean for the project?

BD: Last year, for the book’s publication, we had two other women photographers here in Belgium, Sundus and Aysha. We did talks and events and it was so clear to me that the presence of the women themselves was mesmerising for the audience. Otherwise, it is a westerner again talking on Palestine, telling how they experienced this from their viewpoint as an outsider. Now the audience can hear the women themselves telling real life stories, engaging with them, getting to know them, realising hopefully that they are not heroines nor villains but just people wanting what everyone in the world wants: to lead a normal life. To hear them firsthand makes all the difference. It is also a matter of respect to listen to Palestinians on the Palestinian experience. So, for the opening of the FOMU exhibition in June 2025 we wanted two women, ‘Om Wisam and Nidaa, to come for the opening, but the Belgian government decided at that point not to grant them the visa. We tried again and I’m pleased to say that they’ll be visiting the exhibition.

A: Where do you see the place of art and photography in offering agency to those living under occupation and bearing witness human rights atrocities?

BD: It is not only the photographer or the subject who bears responsibility for the image and its impact. The spectators has the power to participate, engage in dialogue with the image and take it with them wherever they go. This means that, hopefully, the violence, in this case against Palestinians and their heritage, is not normalised anymore. As an audience, we should activate the images we watch. Art, photography and Palestinian culture in general, from within or from the Palestinian diaspora, is essential. We westerners should give them the camera, the pen or whatever tool is asked for. We can assist them in fighting the immense pressure to dehumanise them, erase them, we can offer our connections, network, platform, some institutional knowledge to be their megaphone so they can tell their story.

A: Looking forward, what do you hope ‘Om/Mother will leave behind – as a visual document, a gesture of solidarity and a growing archive of Palestinian life told from within?

BD: First of all, the book was received well. it has been shortlisted for several awards, like the Aperture Book Award 2024 and Book Award at Rencontres d’ Arles 2024. It is in second print, has been distributed all over the world, and its message is loud and clear. As an archive, it holds hundreds of images of Palestinian home life. Moreover, the book is selling very well, which means that the families will receive a nice donation from the project. This is very important, especially because the economy in the West Bank has collapsed since 2023 and there are fewer and fewer jobs. For instance, the water tanks on the roofs of two participating families have already been replaced with the money of the book. The last Iftar feast in the house of Issa Amro, which is the centre of Youth Against Settlements, has also been paid by ‘Om/Mother. Secondly, we will continue the project: not only by doing talks and lectures, together with the women, or by doing exhibitions, but we would also like to extend the project to other families of the village, do workshops with all of them and try out new ideas together. It is great the project is financially beneficial and that it leaves a trace, but it is even more important that we keep this going. We need to ensure that ‘Om/Mother is a living, breathing thing, not just a hit and run, and that it strengthens the community. In the future, we want the women to increasingly take matters in their own hands and only use me in the future as a facilitator. That’s the goal we are working towards.

‘Om/Mother is at FOMU, Antwerp until 28 September: fomu.be/en/exhibitions/om-mother

Words: Emma Jacob & Barbara Debeuckelaere

Images Credits:

All images from ‘Om/Mother. Courtesy Barbara Debeuckelaere.