When asked about the influence of his partner on his photography, Joel Meyerowitz is unequivocally candid: “Maggie’s been part and parcel of my own continued playfulness in photography.” Anyone who’s even slightly interested in photography knows Meyerowitz. He’s created iconic images across a range of genres: chaotic snapshots of Fifth Avenue, the delicate light of Cape Cod and, more recently, still-lifes and self-portraits. His range is amazing and, at 86, he’s still taking pictures. But not many people know his partner, Maggie Barrett, who’s also an artist – a painter, writer and musician to be precise. The two met in the early 1990s, a time when Barrett was successful locally – “a big fish in a small pond,” as she describes it – but soon after their chance meeting she broke her neck. The injury derailed her career as Meyerowitz’s continued to soar. Their relationship is put under a microscope in new documentary Two Strangers Trying Not to Kill Each Other, which explores the strain that unequal recognition puts on a couple.

The film follows Meyerowitz and Barrett over a year as they move between Tuscany, New York and England. Two Strangers never looks away, but we don’t feel any invasive presence. That’s because the directors, Jacob Perlmutter and Manon Ouimet, set up cameras around the couple’s home, allowing them to go about their daily lives without obstructive direction. The directing duo, who are also in a relationship, even lived with Meyerowitz and Barrett during filming. “The minute they walked through the door of our house,” Barrett said, “it was as though we had known each other forever. So because there was that immediate trust, nothing that we did felt scary because we knew that they were going to be very respectful.” Meyerowitz and Barrett’s willingness to put their relationship onscreen, gives the documentary its radical intimacy. The audience observes the pair cooking and playing table tennis; sees them lying in bed together, even kissing each other in the bath. At times it’s almost uncomfortable. Not the sight of intimacy; rather, because it feels intrusive. But they have invited viewers to observe their lives – both the beautiful and the ugly. As Barrett said, “We wanted the nuts and bolts, the nitty gritty.”

The film certainly delivers. It follows the couple over the course of a year, documenting their tribulations – the most dramatic being an unexpected injury, providing some excruciating moments – but the audience is also a fly on the wall of their arguments. Years of built-up resentment come out in what Barrett calls the “confrontational scene,” perhaps the most memorable in the film. In their Manhattan apartment, Barrett unleashes her frustration at being in Meyerowitz’s shadow. “Your life is always more important than me!” she cries. It’s a powerful exclamation, and though she worried how Meyerowitz’s more devoted fans would react, she found that many people have responded positively and personally to that scene. “I think it’s really wonderful that the filmmakers made a point of keeping that inequality in the relationship quite visible,” she said, “because it’s something that is part of many couples’ lives. Not necessarily the woman’s experience, although usually it is.”

At a different moment, Meyerowitz is approached by an eager fan and Barrett, feeling excluded, wanders away. Of course, the concern was there that this dynamic, where all attention would be given to her husband and none to her, would repeat itself in the discourse surrounding the release. “The reality is a lot of people will go and see the film because of Joel,” she said. “And that’s fine because then when they see the film, they’ll realise they’re getting something bigger.” There’s certainly more to Two Strangers than audiences may expect. For one thing, it is not a hagiographical tribute to Meyerowitz. Both its subjects are shown to be flawed, loving and human. The story documents the dynamic that exists between two artists, but there is a university that will be familiar to anyone who has ever been in a relationship, watched a loved one grow older, or has grown old themselves.

Mortality is a third character in the narrative. Death and aging are constant topics of conversation between Meyerowitz and Barrett, who are in their eighties and seventies respectively. Both fear a future without the other. For now, however, the couple are still active and creating. For his part, Meyerowitz attributes his continuous creative rejuvenation to Barrett. “As one ages, you keep looking inside of yourself and asking, is there more?” Meyerowitz said. “Do I have something fresh to say? Can I reinvent myself yet again? I think every artist has cycles, where you discover something that was missing in your work before, and you recognise that open space and you go to it. And with Barrett, throughout our 35 years together, I’ve had six different flourishings. And I can only attribute that to the quality of our relationship. It’s not all about me.”Two Strangers is not about Meyerowitz, or even Barrett, but rather about what it means to be a couple. Unflinchingly honest and painfully tender, it asks how can two people, even after 35 years together, make a life together? If the film, and their relationship, proves anything, it’s not that love is simple, but that struggle can ultimately deepen love.

Two Strangers Trying Not to Kill Each Other will be released in the UK on 21 March.

Words: Henry Roberts

Image Credits:

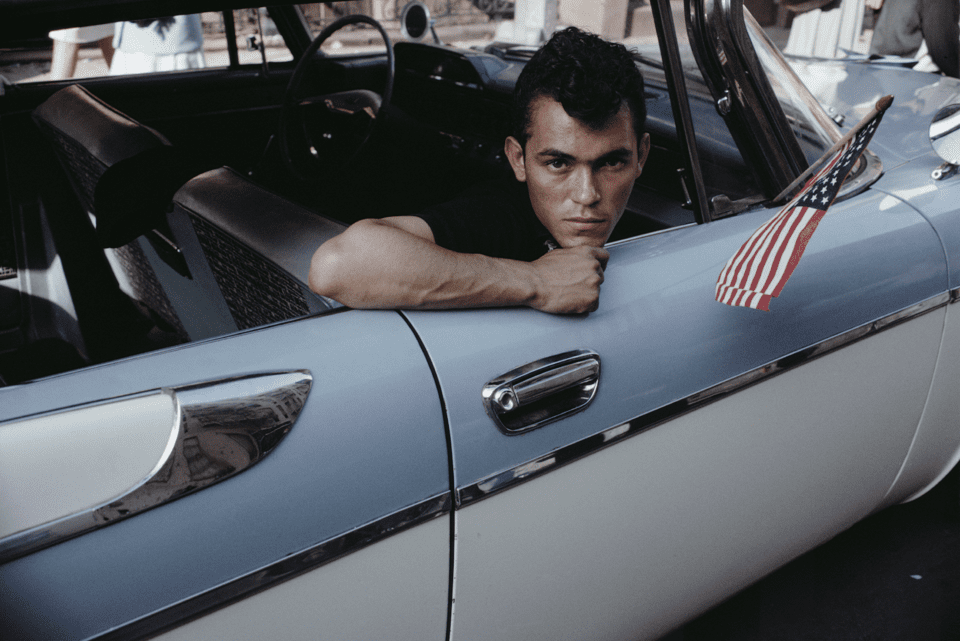

Joel Meyerowitz, Florida, 1967.

Joel Meyerowitz, New York City, 1975.

Still from Two Strangers Trying Not To Kill Each Other©ManonEtJacob_and_FinalCutsForReal

Joel Meyerowitz, New York City, 1963.