“For me it is not a detachment to take a picture. It’s a way of touching somebody—it’s a caress. I think that you can actually give people access to their own soul,” said American photographer Nan Goldin, known for her deeply personal and intimate work. The artist features in the International Centre for Photography’s latest group show, Love Songs, an exhibition that brings together 250 works from 16 contemporaries, including the likes of Aikaterini Gegisian, Clifford Prince King, Nobuyoshi Araki, Karla Hiraldo Voleau and René Groebli. The show is organised in collaboration with the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP), Paris, based on Simon Baker’s original 2022 exhibition. “The idea was to make it feel like a compilation of songs…a mixtape all about love – either inside people’s relationships or inside an intimate circle,” Baker explains. This season, curator Sara Raza remixes the New York presentation of Love Songs, in a reorder of the original visual playlist. Pieces span marriages and holidays, domestic bliss and the pain of separation, even to death and the last days shared between partners. In an assembly of rarely seen moments, the ICP captures the fluctuating state of what closeness and affection mean.

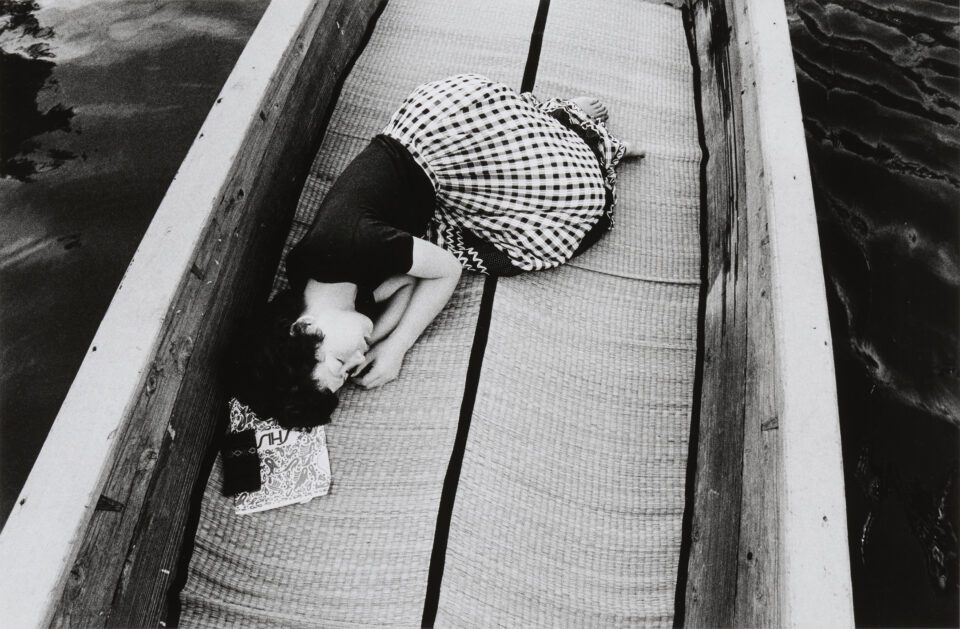

Part of the exhibition is inspired by the canonical works of Nobuyoshi Araki (b. 1950). The oeuvre of the Japanese photographer, primarily known to depict kinbaku, or rope bondage, is subverted. “It was really important to emancipate some of the artists,” curator Raza says. “The work we have selected is a very personal sentimental series of his wife on their honeymoon, her tragic illness after being diagnosed with cancer and eventual passing.” Images borrow from Araki’s landmark book Sentimental Journey (1971), a visual diary of his honeymoon with his partner, Yoko, and Winter Journey (1989-1990), which documents the final months of her life until her death at 42. In one image, Yoko sits on a train in a newly ironed gingham dress, her hair pristinely curled into an updo. In another, she curls into the foetal position on the bottom of a boat, her body small and delicate against a sea of black rolling waves. “Araki offers a front-row seat to a brilliant and devastating love story,” Eloise King-Clements writes in Musée Magazine. Casual smiling shots on rocking chairs dissolve into memorials, as faceless figures hold hands on hospital sheets. In a navigation of devastation and tenderness, Araki blurs the line between insignificance and intimacy.

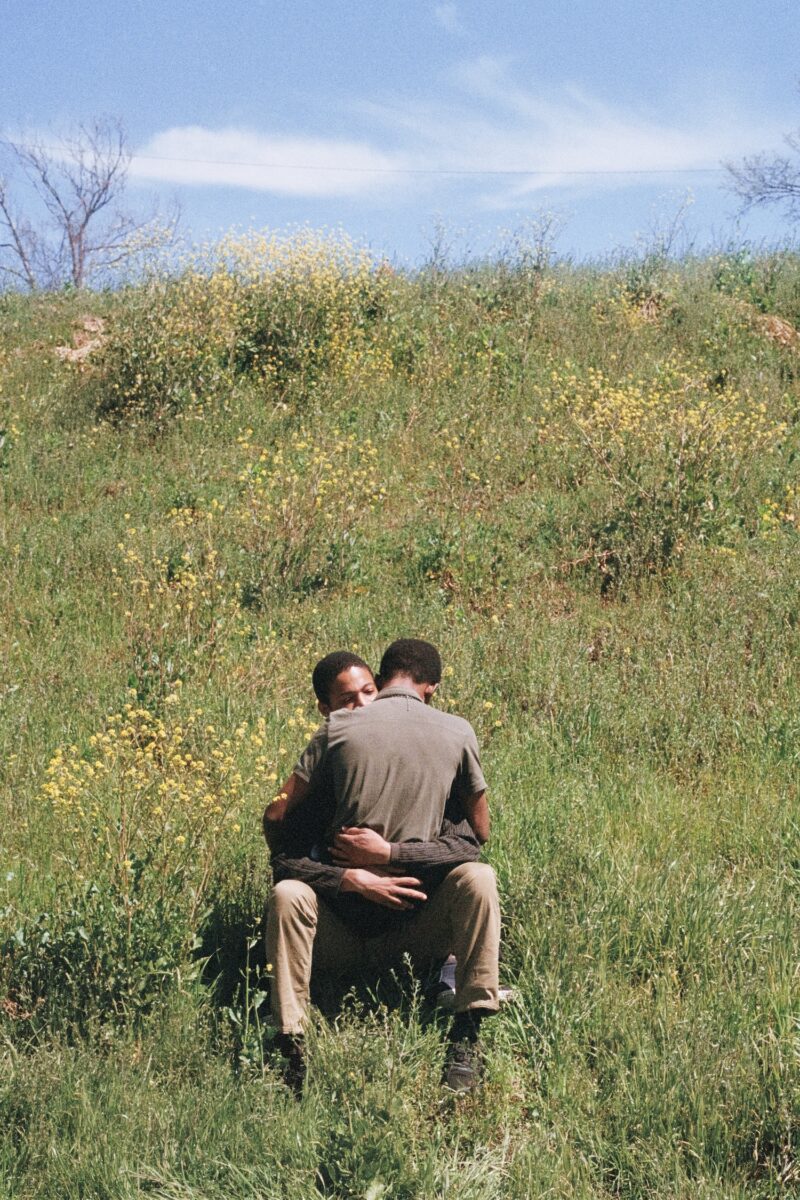

Elsewhere, Clifford Prince King (b. 1993) celebrates queer Black love and liberation. Norms of culture, gender, identity and race are disrupted through colour photographs that draw from real and imagined moments. “Because I am quite a shy person, the camera has always been a sort of vessel for me, an excuse to approach people within a particular environment,” the artist says in an interview with Planet Woo. Portraits are fulfilling, “both emotionally and physically,” as men embrace in verdant fields or pose with pink cornelias, switchblade in hand. In Orange Peel and Biktarvy (2018), a subversion of still-life, fruit rind and medication are placed on a table together — a reference to King’s diagnosis with HIV in 2018. Images capture the early days of the illness, as the artist demystifies misconceptions. He explains, “I want to make other people dealing with the same condition hopeful in return, to show people that there can also be a healthy, loving and successful side to the life of those living with it.” Crucial here is a sense of support, of strengthening already existing networks, where King notes, “I have the responsibility to validate Black gay ancestors and preserve their legacy.” Cinematic shots build on the activism of James Baldwin (1924-1987) as well as the films of Marlon Riggs (1957-1994), Gordon Parks (1912-2006) and Isaac Julien (b. 1960). In a playful exaltation of perspective and desire, images transcend multiple timeframes, creating a tableaux of excitement, camaraderie, joy and romance.

Another highlight is René Groebli’s (b. 1927) L’oeil de l’amour (1952). The series offers up a radical intimacy, as it brings the viewer inside the domestic space of a Paris honeymoon. Groebli chronicles lazy days with a deep closeness, pairing succinctly with Araki’s archive. Every second of time spent together is savoured — from an unmade bed, a bottle of wine on a table, to his wife applying mascara in a mirror. The artist explains, “I tried to convey the typical atmosphere of French hotel rooms. There were so many impressions: the poor-looking furniture in a cheap hotel, the ‘Amors’ embroidered on the curtains. And I was in love with the girl, the girl who is my wife. I think a series of photographs should be compared with a novel or even a poem rather than a painting: let us tell something!”

In Another Love Story (2021), Karla Hiraldo Voleau (b. 1992) depicts a summer of romance with a twist. Here, desire reaches a dangerous level of entanglement. The artist restages photographs from a former relationship with a man known only as X. After discovering that he had been leading a double life and living with another woman, Voleau cast a model to play the role of X. Cherished moments from their relationship are reenacted in previously visited locations, as the work leads up to the moment of betrayal. Images mimic an Instagram feed, presented in 13 panels that manoeuvre between picturesque shorelines to mid-kiss selfies. Gem Fletcher writes in British Journal of Photography, “Voleau reflects photography’s slippery role as the unreliable witness…It lays bare the social social contract to memorialise our relationships online, the pressure to perpetuate perfection and the chokehold of keeping up appearances.”

The commodification of photographs is further explored by Aikaterini Gegisian (b. 1976). In Handbook of the Spontaneous Other (2019), pop culture materials from the 1960s and 70s are repurposed. Adult magazines, travel journals and National Geographic issues are subject to a process of “decollage.” Archived images overlay in a riotous show of colour and national identity, reminiscent of the playful assemblages of Hannah Hoch (b. 1889) and Linder Sterling (b. 1954). In Blue (2019), volcanic explosions fold into airport runways and pelvic shots, whilst in Yellow (2019), the top of an arm transforms into a blooming cactus. These frames ask viewers to reexamine their understanding of appearance, nature and pleasure in a Western context. Gegisian dismantles notions of orientalism and tourist photography — background colours borrow from Persian and Indian miniatures — as the artist satirises perceptions of an exoticised “other.” Fetishised images taken from adult magazines are severed from their context, instead laid alongside images of flowers or insects. The series continues on from the artist’s essay film My Pink City (2014), that portrays a post-Soviet Yerevan, as it locates what it means to be a woman in a globalised world.

“These works offer a window into the themes of aftermath, contradiction, collision, desire, distortion and reality,” says curator Sara Raza. Photographs take viewers through personal, often unseen stories, chartering the arc of desire. The process relies on subversive practices, using montage to interweave varying attractions and emotional states. Despite the complexity of what is on show, resoundingly, ICP offers up a direct and open narrative. What pervades is a sense of care — through both private and public spaces — in a declaration of what it means to connect and more broadly, to love.

Words: Chloe Elliott

Image Credits:

1. Clifford Prince King, Lovers in a Field, 2019. © Clifford Prince King, Courtesy STARS, Los Angeles

2. Nobuyoshi Araki, Sentimental Journey, 1971. Collection MEP, Paris. Gift from Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd. © Nobuyoshi Araki, Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery

3. Clifford Prince King, Lovers in a Field, 2019. © Clifford Prince King, Courtesy STARS, Los Angeles

Clifford Prince King, Conditions, 2018. © Clifford Prince King, Courtesy STARS Gallery, Los Angeles

4. René Groebli, from The Eye of Love, 1952. Collection MEP, Paris. © René Groebli, courtesy Galerie Esther Woerdehoff

5. Karla Hiraldo Voleau, from the series Another Love Story, 2022. © Karla Hiraldo Voleau

6. Aikaterini Gegisian, Handbook of the Spontaneous Other (Yellow 5), 2019 © Aikaterini Gegisian