In the beginning, there was a pulse. That fundamental fact of living organisms – and how a society so obsessed with control and automation depends on the involuntary spasms of muscle tissue – goes to the heart of a series of large-scale installations by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (b. 1967) built around the vital signs of participants. The concept, he says, came to him when his wife was pregnant with fraternal twins in 2006. Lozano-Hemmer listened simultaneously to the male and female embryos’ heartbeats with different ultrasound machines and, sure enough, each one was unique and phased in and out like a minimalist piece by composers Steve Reich or Conlon Nancarrow.

That same year, Lozano-Hemmer created the first work of his Pulse series, Pulse Room, where visitors hold sensors that transmit the corresponding pulse to an incandescent lightbulb that flickers to its rhythm with amplified sound, along with 210 other lightbulbs hanging from the ceiling in a large, darkened room. For a brief moment, the entire space is lit to the pace of that single heartbeat — quickly for the frenetic child, slowly for the trained athlete or confusingly for the arrhythmic patient — for all to see. Once the participant lets go of the sensors, each individual light flickers one after another then all at once to the rhythms of those previous, creating a cacophonous, syncopated whole. “The flashing lights of the heartbeat are disorienting. It’s not necessarily pleasant — light to hide and light to blind,” Lozano-Hemmer said as he previewed his show at the Hirshhorn.

The piece is part of the largest interactive technology show at the post-war art museum, which has presented several blockbuster, Instagram-friendly shows under director Melissa Chiu. Last year, its exhibition of six Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Rooms was so popular that the Hirshhorn had to implement crowd control and set time limits, which made the selfie even more of an end to itself. But Lozano-Hemmer’s show has a different feel altogether. The space – which offers just three installations spread across the Brutalist donut-shaped building’s second floor – provides just enough breathing room for pause and contemplation.

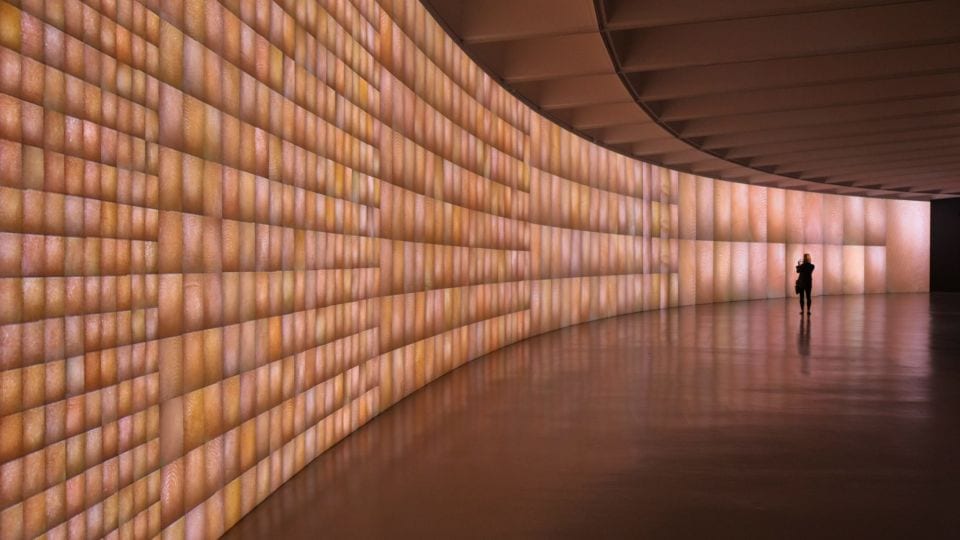

In each case, visitors’ biometric data, compiled via heart-rate sensors, create unique kinetic and audiovisual experiences. Yes, this is the same kind of information grimly computed for identification and control in places like the fraught US-Mexico border. But anonymised as in Lozano-Hemmer’s work, it becomes an instigator of community. Pulse Index, presented here in its largest scale to date, displays the fingerprints and heart rates of the last 3,911 users across a large projection that fills the gallery wall. Each new participant thus erases the data of the last one in the sequence. Pulse Tank, in contrast, is a game of light and shadow not unlike Plato’s cave. When visitors use various sensors placed around three large, illuminated tanks each filled with about 70 gallons of water – just one inch deep – the resulting ripples are projected on the wall. The shadow patterns are most complex when one or more people use sensors at a same tank.

While recognizing his debt to half a century of light art, Lozano-Hemmer is quick to distinguish himself from other works that fall under that category, namely those by James Turrell (b. 1943). “I do like the macabre side of it, but it’s not all macabre, it’s presence and absence, light being presence and shadow being absence and how they are interdependent and they co-exist and at any point in time, you cannot separate them,” explained Lozano-Hemmer. “This idea that light is violence, that it’s generated by these out of control explosions is a metaphor that I really like. That’s why I am different than this search for spiritual light. I admire and love it, but that’s not what I am about.” And don’t try categorising him as “new media” either, a term he says he hates. He points to precedents like Marta Minujin’s La Menesunda (1965), and its use of surveillance cameras and live video. Case in point, the exhibition begins with an overview of pioneers of light and media art.

Growing up in Mexico City, Lozano-Hemmer was immersed in a world of performance and limitless possibilities. His parents owned the Los Infernos nightclub, which perhaps explains his obsession with light and darkness. While there is a playful, crowd-pleasing quality to his work that makes it a sought-after commodity for museums, galleries and other venues seeking ever larger audiences, it also comes with a darker side, reflecting German writer Goethe’s (1749-1832) comment that “where the light is brightest, the shadows are deepest.” For example, the artist invited people to enter a hermetically-sealed room and breathe the air previously exhaled by other participants in Vicious Circular Breathing (2013), a work that comes with warnings for asphyxiation, contagion and panic — and that Lozano-Hemmer refuses to use himself. “It’s disgusting,” he said in a surprising comment about his own creation. “I really like that responsibility, the idea that participation is not just something empowering and so on, but something that cannot be divorced from the desire to control people, that does have that violent, predatorial control. I’m part of that problem. I’m not trying to pretend I’m outside of it.” His interest in control and surveillance is one shared with many other artists working today, notably Trevor Paglen (b. 1974), who has an ongoing show nearby at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Lozano-Hemmer likes to think big, and politically. He makes no secret of his deep distaste for the American president, Donald Trump. His Border Tuner, a participatory project set to open in October, will connect the two cities central to the US immigration crisis — El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico — with a bridge of light created by powerful robotic searchlights visible for up to 10 miles, a “switchboard” of sorts. It’s the same kind of lights used by the military… or nightclubs. Visitors can connect or separate the lights via several interactive stations on each side, and when the lights connect, a channel of sound opens up and allows people on either side of the border to speak and listen to one another. “It’s the single most important thing I’m doing,” Lozano-Hemmer said. The cities are “completely and diametrically opposed to this Trumpian desire for a wall and division,” he added, pointing to the economic, environmental and historical connections that already exist between them. “When I have grandchildren, I want them to say, ‘Grandpa, when fascism took over the United States, what did you do?’ And I want to be able to come up and say, well, this is what I tried.”

Olivia Hampton

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Pulse. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Until 28 April. For more information, click here.

Credits:

1. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Pulse Index, 2008 in Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Pulse at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, 2018. Photo: Cathy Carver

2. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Pulse Tank, 2010 in Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Pulse at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, 2018. Photo: Cathy Carver

3. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Pulse Room, 2006 in Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Pulse at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, 2018. Photo: Cathy Carver