Every day, we open our phones, toggle between different feeds, then slide back to another screen – an iPad, TV or laptop. A resounding thought emerges from this constant back-and-forth: “I just can’t keep up.” In May 2025, the writer Jia Tolentino published a widely resonant New Yorker piece titled My Brain Finally Broke. She unpacks the dystopian, paralysing exhaustion of carrying devices with literally endless information that we can’t even parse for truth. She brings Richard Seymour’s book The Twittering Machine (2019) into the discussion, arguing how our collective addiction to these systems occurs “in a society that is busily producing horrors.”

Various journalistic outlets partially trace this phenomenon to the accelerating proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data across massive – and selfish – corporations. There’s a term for this: the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Popularised in 2016 by World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab, it’s a catchall for the major technological changes occurring globally in the 21st century, spiralling into a form of industrial capitalism characterised by AI, advanced robotics and gene editing. It’s worrying that so much of this is happening unchecked – or checked (read: controlled) by power-hungry and irresponsible people. It relies on the fact that the processes behind them are so specialised, meaning opaque. We don’t know the why and the how. And the more in the dark we remain, the more these technologies can be used against our wellbeing and interests, even our very rights as humans.

Felicity Hammond brings a torchlight into the shadows. An established artist based in South London, Hammond fuses photography with sculpture, installation and various media. “I am interested in how photographic processes / the printed image is entangled with the material world. Whether that’s through the way it is used in large-scale advertising campaigns and plastered around the city, or how photographic technologies emerge from the extraction of raw materials … The practice I have developed treats the image as one component amongst other objects, surfaces and technologies.”

Hammond was born in 1988 in Birmingham. She received an MA in Photography from the Royal College of Art in 2014, then a PhD in Contemporary Art Research from Kingston University in 2021 (she is now a senior lecturer in the MA Photography programme there). She became fascinated with how photography is a networked medium that, in a postmodern society, is constantly touching us in some form or another. “When my practice started developing at art school, I was turning my lens towards quite low-fi computer generated images that imagined future urban sites. There was a key early moment when computer-generated marketing images started to suddenly dominate the urban landscape. It was in the early 2010s, and many parts of London were subjected to fast-paced and aggressive urban re-generation projects.”

These themes formed the core of Hammond’s first institutional solo show, Remains in Development, at C/O Berlin and Kunsthal Extra City Antwerp in 2020–2021. Since then, she has exhibited far and wide, from Beijing Media Art Biennale and Transmediale in Berlin, to the Centre for Visual Art in Denver, Bologna’s Fondazione MAST and Garage Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Over the years, she has won and been short and longlisted for key awards, fellowships and grants, such as the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, FOAM Talent and the Lumen Art Prize. Though her work has traversed many different places, physically and conceptually, London remains an anchor point. “I am really influenced by the outskirts of the city – the post-industrial landscape of London, sites that I have occupied for the last 15 years.”

Along with her environment, Hammond is inspired by science fiction, the mechanics of which influence her own grammar as an artist for whom “the power of speculative language … is a key focus.” She cites J.G. Ballard, as well as Mark Fisher, who she calls “instrumental” to her growth – “his thoughts on failed futures and pastiche have really informed the way I think about how digital technologies are operating on these kind of mediocre levels.” Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005) is another reference. Hammond also looks to visual artists – like Anne Hardy, Anthea Hamilton, Heather Phillipson and Laura Grace Ford – for their meticulous world-building skills.

One of Hammond’s latest bodies of work, 18 months in the making, is Variations, commissioned via the Ampersand/Photoworks Fellowship, a biennial opportunity for mid-career artists. The project is an evolving, four-part photographic installation. It drills down into the processes behind computational image-making and generative AI, exposing the nerve endings of a sprawling, sinister ecosystem of land, resources and labour, upon which the machine learning software relies.

Variations spans four venues: Photoworks Weekender in Brighton, QUAD in Derby as part of FORMAT International Photography Festival; The Photographers’ Gallery in London (27 June – 28 September); and Stills: Centre for Photography in Edinburgh (7 November – 7 February). Each location offers a unique and evolving chapter of the project, representing a particular aspect of generative AI’s construction, like the shipping of raw materials, extraction and surveillance, model collapse via feedback loops of data, archive and waste. “The curatorial framework mimics the four variations often provided by text to image generative AI software. Rather than producing a single exhibition that tours four venues, I wanted the work to reflect the variations on a single idea / image that contemporary technology offers us.” Eventually, Hammond will compile this process in a four-chapter print publication.

The project’s second part, on display now, is V2: Rigged, a massive feat constructed with powder coated steel and aluminium, MDF, inkjet printed PVC banner and vinyl, paint, cable, camera, mirrors and PLA prints. It’s the megamachine cracked open: audiences must come face to face with the intricacies of how machine learning actually works – a combination of various brutal extractions – brought together by the rig, a piece of supportive equipment used in mining as well as photography. V2: Rigged appears partly as a drill head, processing plant, and camera: a composite installation-machine.

It’s a complex piece that gets more impressive when you consider it is a part of an even larger whole. For the next chapter, V3: Model Collapse, Hammond is making “re-enactments” of AI generated pictures, that are themselves variations of V2: Rigged. “It demonstrates the hallucinatory potential of images made via systems trained on AI generated visuals. These particular works are made in the studio where I am making stage sets, painting and collage, all of which re-enters photographic space via the camera.” The final chapter, V4: Repository, will examine the role of data storage centres.

Hammond’s installation stands out in more ways than one. It is currently showing at the FORMAT International Photography Festival, which platforms lens-based media, photography and archives from around the world. Its theme this year is Conflicted, acknowledging not just the major genocides, wars and political tensions we are living through, but also the frames of thinking we have to adopt to cope – marked by doubt, paradox and contradiction. The festival is renowned for its open call, through which five artists are selected to exhibit. For 2025, they are Christopher Gregory-Rivera, Jenna Garrett, Lo Lai Lai Natalie, Sujata Setia and Thero Makepe. Their practices span topics such as domestic abuse in South Asia, farming in Hong Kong, and Apartheid in South Africa.

The themes of Hammond’s Variations recur across the wider FORMAT Festival programme. Xueyi Huang (Snow)’s No.27 Tong Poo Road is a surrealist AI-generated video that reflects upon the old house in Guangdong Province where the artist was born. Twenty years ago, it was demolished to make way for a new residential area. Aside from illuminating a younger generation’s perspective on urban development and family history, it also reflects on the role of the camera. This work does not demonise AI, nor present itself as simply defined by the medium; it asks us to consider what AI’s capacity for expressing sentimentality and personal storytelling might be.

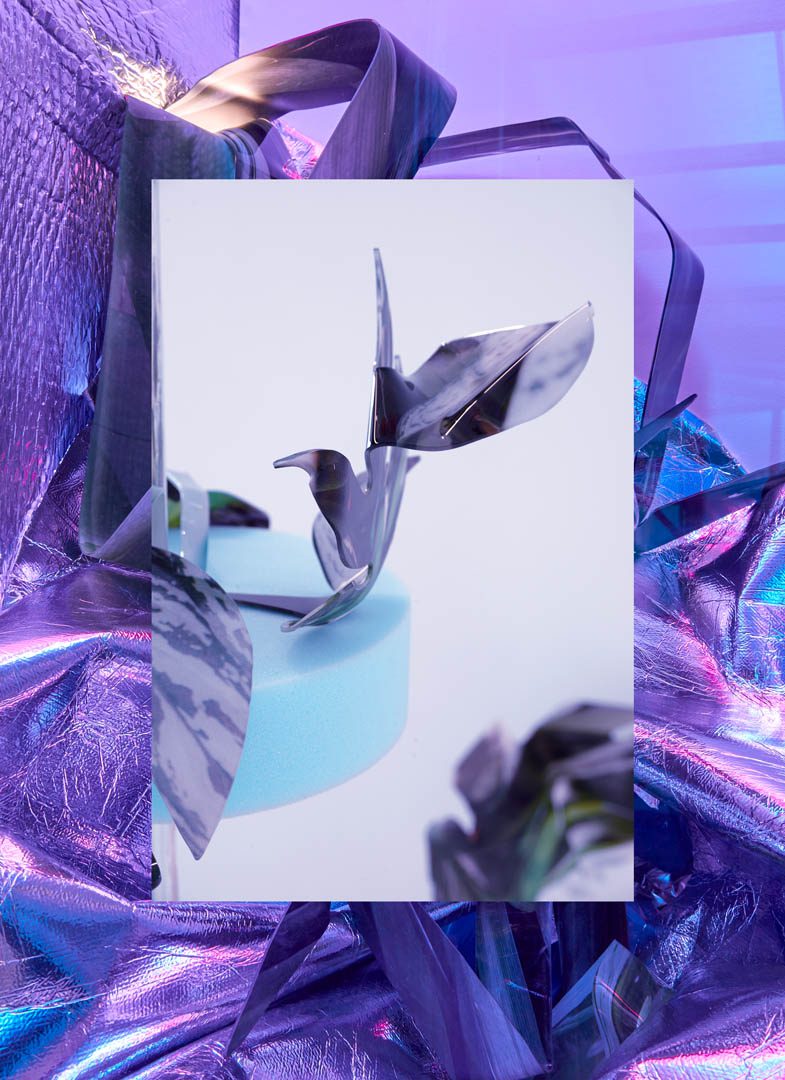

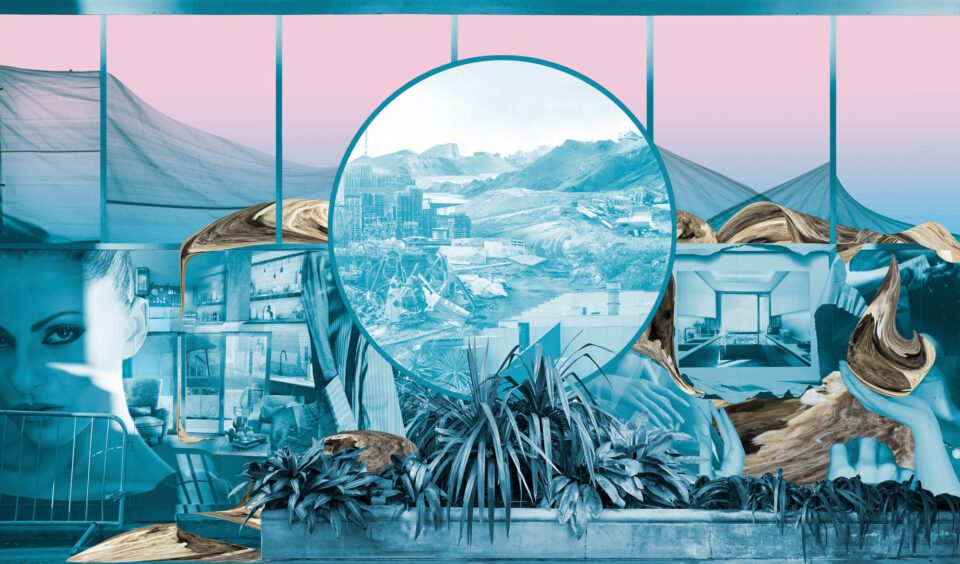

Hammond has noticed, like most of us, a shift towards AI-generated images becoming more commonplace. Careless renderings, produced by machine learning-based programmes, are being used across a range of contexts, including architecture. There’s a through-line here to Hammond’s earlier works, like Capital Growth (2015), Post Production (2018) and Arcades (2018), with the latter in particular forming a precursor to Variations. The project critically examined computer generated images used for commercial development projects, picking up on their errors. The fact we can virtually visualise structures before they are built feels time-warping, and Hammond’s project brought to the fore how property continues to be planned, prospected, bought and sold based on unreal images of things that don’t really exist.

“I do feel confident in saying that I don’t see how [AI] can ever replace the human desire for creative production,” Hammond adds. Still, its growth appears ferocious. Plus, there are other risks, most saliently the already degrading climate. In a 2024 Forbes article, Cindy Gordon reported that “AI’s projected water usage could hit 6.6 billion m³ by 2027” due to increasing demand for services resulting in more water needed for cooling data centres. Such facilities already guzzle an enormous amount, “using cooling towers and air mechanisms to dissipate heat, causing up to 9 litres of water to evaporate per kWh of energy used.” This is beyond urgent.

Hammond’s work continues to evolve in tandem with her own perspectives on developments in AI, CGI and machine learning, and it is a useful source to help viewers digest all this rapid and frankly scary change – the perils of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The artist shares that she is now developing projects on cars. “I have been interested in the way that the car has become another camera in society – another tool of surveillance. As autonomous vehicle technologies have developed, the car extracts data, images the environment in the form of LiDar scans, object detection technologies and 3D mapping, and also relies on the images that it builds of the landscape to function.” Beyond the car, she’d like to look at other technologies, from aircraft to military. “Operational images are at the centre of my investigation here, and there continues to be new photographic applications to explore.”

Variations The Photographers’ Gallery, London 27 June – 28 September

thephotographersgallery.org.uk

Words: Vamika Sinha

Image credits:

1. Felicity Hammond, Fragment 04, (2018), from Arcades. Image courtesy of the artist.

2. Felicity Hammond, Fragment 08, (2018), from Arcades. Image courtesy of the artist.

3. Felicity Hammond, Capital Growth, (2015). Image courtesy of the artist.

4. Felicity Hammond, Post Production, (2018). Image courtesy of the artist.

5. Felicity Hammond, Fragment 03, (2018), from Arcades. Image courtesy of the artist.